THE CONVERSATION

How Terry Hall and The Specials defined the sound of youth and disillusionment in Thatcher’s UK

Their line up of black and white musicians was a mission statement for a fractured nation, while Hall’s doleful vocals starkly illustrated the politics of disillusionment.

Terry Hall, who has died after a short illness at 63, was the voice of The Specials, an iconic band that bridged the youth sub-cultures and mainstream pop of the late 1970s and early 1980s, embodying the sound of disaffection in Thatcherite Britain.

Born and raised in Coventry, Hall brought a distinctive stance, and sound, to British pop. As frontman of The Specials and then Fun Boy Three, his simultaneously deadpan yet melodic vocals, flecked with his native Midlands accent, belied the eclecticism that underpinned his music.

His sardonic delivery, likewise, was the filter through which he reflected a sense of alienation, both national and personal. He was plagued by mental illness after being abducted by a child-abuse ring aged 12, which he later alluded to in Fun Boy Three’s song Well Fancy That. By 15 he had left school and drifted through a series of jobs, including bricklayer and hairdresser, before gravitating towards music, first punk and then ska.

It was the latter that particularly infused the sound of The Specials, initially formed as The Coventry Automatics in 1977 by keyboard player and songwriter Jerry Dammers with Hall joining soon afterwards. Early hits were a mixture of Dammers compositions such as Too Much Too Young and covers of ska classics like A Message To You Rudy, fronted by Hall and Neville Staple, who had moved to England from Jamaica aged five.

British rock band ‘The Specials’ perform on the stage during a concert at the 16th Benicassim International Festival (FIB) in Benicassim, eastern Spain, on 17 July 2010. EPA/DOMENECH CASTELLO

The mixed-race aspect of The Specials and, latterly, Fun Boy Three was more than just an element of their sound. It was a mission statement for a fractured nation. 2 Tone referred to the genre fusing ska, reggae, punk and new wave – of which The Specials were among the primary exponents – but it was also the name of their record label, founded by Dammers.

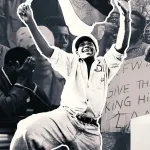

The band emerged in parallel with Rock Against Racism, a movement responding to the rise of the far-right National Front in the mid-to-late 1970s and, more specifically, comments that Eric Clapton had made in support of former Birmingham MP Enoch Powell, whose incendiary and racist rhetoric helped to stoke tensions in the Midlands and Britain at large.

Catching the mood

The broader politics of disillusionment were most starkly illustrated on The Specials’ number one hit Ghost Town, Hall’s doleful vocals providing melodic punctuation amidst the group’s wailing and the spooky, fraught instrumental backing.

The song’s evocation of dereliction matched the fractious mood of the time as race riots rocked the country alongside deindustrialisation and unemployment reaching, at that time, a post-war high of 2.5 million – it would approach 3.5 million by the middle of the decade.

The politics of the Ghost Town were explicit, and resonated broadly. Future Labour party deputy leader Tom Watson described its effect:

“I was 14 years old – the summer after the notorious 1981 Tory budget. Ghost Town spoke to me and every other teenage kid. I remember the school careers officer telling me that if I didn’t smarten up I wouldn’t get a job in the local carpet factory. My Ghost Town was Kidderminster, but it could have been any Midlands town. We all wore our Fred Perrys and worshipped The Specials.”

Things weren’t much better in The Specials’ camp. As well as intra-band tension, their tours were marred by audience violence and confrontations with the National Front. Hall recounted having to leave the stage to stop fights, and “casualties all over the dressing room”.

At the peak of their initial success, things fell apart. Hall, Staple and guitarist Lynval Golding quit the band the same night they recorded Ghost Town for Top of the Pops. And while Dammers would resurface with The Specials AKA, the trio launched as Fun Boy Three, enjoying another string of chart hits.

Personal and political

Here, again, the variety of Hall’s musical influences came into play. Fun Boy Three’s duets with girl band Bananarama included a Motown cover and a 1939 jazz classic, reconfigured with sparse pop production. As before, though, pop sensibilities were shot through with a heavy measure of irony and lyrical bite, like on their debut single The Lunatics (Have Taken Over the Asylum).

Fun Boy Three split after two albums, but Hall’s output remained steady. He went on to form Colourfield in 1984 producing a hit with Thinking of You. He was an active collaborator with likes of Dave Stewart of The Eurythmics and Damon Albarn throughout the 1990s and 2000s before a reformed version of The Specials (minus Dammers) began touring and releasing new music in 2008. Their last album topped the charts in 2019.

He is perhaps best remembered for giving voice to the turbulent era in which he emerged. But Hall’s political commitment was a strand that ran throughout his career, from his initial shock that some working men’s clubs in Coventry employed a colour bar – only admitting white people – in the 1970s, to the reflective elements of latter-day Specials albums. As he put it, describing the impetus behind 2019’s Vote for Me:

“From growing up in a really staunch Labour, trades union household, when I was a kid, it was almost pantomime. There were goodies, and there were baddies. And now, I can’t find many goodies.”

Leaving the stage much too young, Terry Hall will always be remembered for being musically exploratory, his voice and attitude embodying an aesthetic in the bleak period of early 1980s Britain, at the point where pop met protest. DM/ML

This story was first published in The Conversation.

Adam Behr is a Senior Lecturer in Popular and Contemporary Music at Newcastle University.

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

The use of lyrics to expose the inequities of UK life, at that time, was also employed by UB40, The Clash and others. It motivated the young and terrified the establishment as they could not explain their way out of such a precise expression. Songs were the legitimate opposition and bands united, like Red Wedge, Free Mandela, Live Aid.. taking collective responsibility, while Governments uttered platitudes. The music of the late 70s – early 90s were iconic times as they engaged the younger generation in shaping their future and collective responsibilities.