BOOK EXTRACT

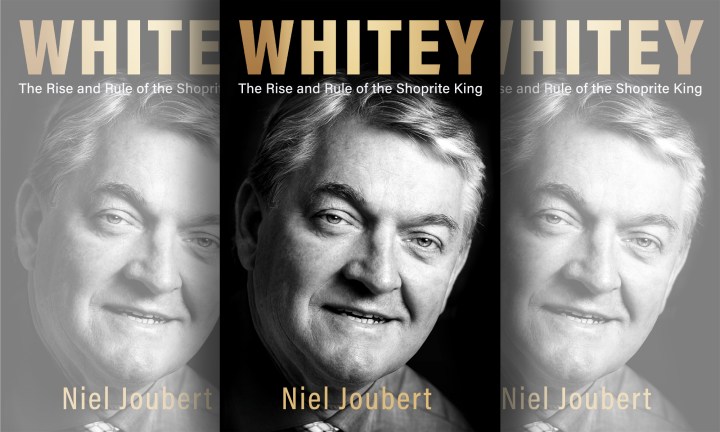

‘Whitey: The Rise and Rule of the Shoprite King’ – on takeovers and turnarounds

James Wellwood Basson, known as ‘Whitey’ built the Shoprite group to become the biggest retailer on the continent and one of the 100 biggest in the world. Financial journalist Niel Joubert tells his story.

For this authorised biography, financial journalist Niel Joubert was given access to the Bassons’ archives and interviews with Whitey and his inner circle; here, he “recreates Whitey’s story in rich detail: from his childhood on a Porterville farm to his mentorship at Pep Stores (under the renowned Renier van Rooyen), achieving his lifelong target of eclipsing Pick n Pay, and conquering Africa.” Read the excerpt.

***

A smallish clothing boutique chain called Papillon was the first struggling business Whitey had to turn around. But the attempts to transform this caterpillar into a butterfly would soon suffer their first setback. ‘The first step in turning the business around was to close its head office in Johannesburg and move it to the Cape,’ Whitey recounts. ‘We found premises that were within walking distance of Pep’s headquarters in Kuils River, and that worked well.’

The move to Cape Town entailed a huge furniture removal truck having to pick up machinery, fabrics and the patterns for the season’s fashions in Johannesburg and transport the goods to the Cape. ‘The youngster who drove the truck then decided to pay a visit to a girl he knew near Potchefstroom,’ relates Michael Lester, a colleague of Whitey’s at Papillon. ‘Along the way, the road changed into a narrow gravel road that ran over a very narrow single-lane bridge. Needless to say, the truck with all our supplies tumbled off the bridge, and our fabrics and patterns went down the river.’

Whitey and Leon van Niekerk, who had been appointed to help bring about the Papillon turnaround, hurried to Johannesburg and went with Lester and every available Pep regional manager to the accident scene. ‘We spent hours on the bridge trying to sort out the mess, and almost everyone got sunstroke,’ Lester recounts.

Back in Cape Town, Whitey had his work cut out for him because Papillon had been underwater even before the season’s fabrics and patterns had gone downriver. According to Whitey, he had been overseas when Renier had acquired Papillon, and the latter had only told him about the purchase on his return. ‘And he said I’ll be happy, because it was bought at the NAV (nett asset value). But when we did the sums properly, we saw that the NAV was minus and Papillon was in fact bankrupt.’ ‘Mr Van Rooyen announced on 6 June 1976 that Pep’s takeover bid for Papillon, a firm with 14 fashion boutiques, has been successful,’ an article in Pep Nuus read.1 ‘The stores are all situated on the Rand and in Pretoria. The group has more than 220 employees and their own factory that supplies about 60 per cent of their requirements. The turnover for the year ending February 1976 was R1,8 million . . .’

The plan for Papillon was that it would continue trading as an independent group. The Pep team were optimistic about Papillon’s prospects – they anticipated that the group ‘would still expand enormously in future . . . and that they could make as big a breakthrough in the clothing market for the higher-income group as Pep Stores had made earlier in the lower-income group’.

The article painted a rosy picture, but the initial adversity was not limited only to the supplies that had landed in the river. The founder of Papillon was Jael Mankowitz, and at the time of the takeover he was still in charge. Just before the takeover Mankowitz had ordered a lot of fabric in Japan, and they had been unable to stop the order. ‘Every month thousands of rolls of this material would arrive. So we made all kinds of clothing we could with this material. I think it took us two or three years to get rid of the stock!’

But Whitey enjoyed it, so much so that he even helped to distribute pamphlets. Since there was no money for advertisements, they had to resort to ‘knock and drop’ – in other words, pamphlet distribution – in residential neighbourhoods and particularly at women’s residences.

‘Papillon was a nice business. It was exciting, sort of an after-hours job, which gave me great pleasure.’

Papillon was Pep’s first step towards a more affluent market. The concept was simple. They purchased the fabrics, manufactured the clothing themselves, and sold it in small boutiques at prices that were lower than those of Foschini and Truworths. They also devised and designed the fashions themselves, although some ideas were ‘borrowed’. It was rumoured, for instance, that Whitey once passed a girl in the street who was dressed in a striking cat suit. He stopped her on the spot and asked whether she would be so kind as to walk into the nearest store, buy anything of her choice, and give him the cat suit so that the design could be copied. Whitey also used to say he had to ‘feel’ the clothing because he had to ‘test’ the fabric.

‘Also, we only sold certain sizes. At Pep we had more sizes because Renier always said people complain if they can’t find their sizes. And then I said one day with my big mouth, if we’re going to stock those sizes at Papillon, we’ll be bankrupt within a year because those people aren’t my customers.’ This did not go down well, and Whitey and Renier started bumping heads about other aspects of Papillon too. Whitey wanted to turn Papillon around, but Renier thought Whitey was spending too much time on Papillon. ‘I told him: if you or someone else can manage the business better, then do it. So we got someone else, who really messed it up. For instance, previously the sales ladies who worked in the stores were mostly younger girls, and one just made peace with the fact that many of them wouldn’t turn up for work on Mondays. But then they started appointing older ladies, and culturally it was a wrong move,’ says Whitey.

Only four years after Van Rooyen acquired Papillon, Pep Stores got rid of the boutique chain, which had expanded to 43 stores in the meantime. Some were closed and the rest were sold. Where possible, the premises were sublet. Papillon’s sales amounted to less than two per cent of Pep’s total retail sales, and the closure did not have a significant impact on the company.

The impact on Whitey was more substantial. ‘It was the only business I walked away from that had not become successful and profitable,’ Whitey says. ‘I’m still a bit sad about it because I enjoyed it very much.’ Papillon was modelled on fast fashion for a more affluent market, which did not quite fit into the Pep philosophy. For a while Whitey had forgotten his philosophy – that you should focus on what you are good at. But he would not make the same mistake again.

***

Half Price Stores was to be the first large struggling retail chain Whitey had to take over and turn around. ‘It was my first big takeover, where I really learnt how to negotiate,’ Whitey relates. ‘And, secondly, I learnt that you needed to understand the business and examine the figures carefully. Audited figures mean nothing if you don’t understand the business.’ Jimmy Fouché was also part of these negotiations. ‘During the acquisitions Jimmy was my right-hand man and knew exactly what was going on,’ Whitey adds.

A few years earlier, Fouché’s future at Pep had still been uncertain. ‘When I joined Pep, Renier said he didn’t really want guys with degrees because they didn’t last long. Except if they were financial people, then he wanted the formal qualifications,’ recounts Fouché. But Whitey told him he should hang in there – there were many opportunities at the company.

Whitey confirms this: ‘Renier wasn’t always very good with guys with degrees, and they tended not to last long.’ And Jimmy was on the same trajectory. ‘Then I said, I’ll take Jimmy and he will make it.’ So he took Jimmy under his wing. ‘He sat close to me – I had a door sawn open between my office and his, so we knew what was happening in each other’s offices.’ Fouché would eventually become Pep’s company secretary and a director of Shoprite.

According to Fouché, ‘Whitey used to involve himself in everything and was very interested in the operational side of retail. He always knew what was happening on the shop floor. He didn’t sit in an ivory tower.’ That was also the case with the investigation into Half Price Stores. Whitey, Frank Weetman and Stephen le Roux travelled across the country to determine whether the stores were worth their while, and what they were prepared to pay. Whitey recounts: ‘I drove an old Audi Renier had said I should use, with R2 000 in my pocket for fines. Among the three of us, we visited all the Half Price stores in South Africa.’

Although this clothing retail chain was much smaller than Pep, it had long been a thorn in their side. The stores of the two groups were often located next to or opposite each other. This led not only to price wars but also to a fierce rivalry that would sometimes degenerate into physical confrontations. ‘From time to time we had put out feelers for Half Price Stores,’ says Fouché. ‘Our branch managers always used to keep an eye on our competitors on the other side of the fence, usually further down the street. Half Price Stores was actually just based on the Pep concept. When we displayed something in the window, they would follow suit.’

The staff of the two companies had no time for each other, and the hostility was evident during Pep’s takeover of Half Price Stores in 1978. In fact, Half Price Stores’ employees did everything in their power to thwart Pep’s bid. The acting managing director, Hugh Ashby, said his employees saw themselves as the David ‘taking on Goliath’. And at times they would literally come to blows. In one case, the manager of Pep’s Claremont branch appeared in court for having assaulted two Half Price employees who, according to him, had ‘spied’ on his store by writing down prices outside his store windows. The manager, Gert Prins, ended up admitting he had boxed the Half Price manager’s ears and then ‘planted’ the notebook in a flower pot next to the entrance of the store.

According to Ashby, merging with Pep was ‘inconceivable’ to many of his employees. And Whitey describes Sam Stupple, the founder of Half Price Stores, as a nuisance. ‘I realised he had got hold of Pep’s information somewhere. He would phone me out of the blue on a Monday or a Tuesday, and then he would say he saw that this product had done well, or that one had done badly, but he wasn’t mentioning products in alphabetical order, he was talking exactly according to the computer numbers. So I knew he was sitting with our sales figures in front of him – and that someone was providing him with the information.

‘So I told one of the buyers, let’s throw Sam Stupple a dummy and let on that we’re going to start selling food. And he fell for it hook, line and sinker. The next moment, he was buying rice from India and you name it.’

But in 1977 Half Price Stores was in trouble. The company, with its 144 branches countrywide, suffered huge losses and was put under judicial management. The Pep team were confident that they could save the company and return it to profitability. But an intense battle lay ahead.

In April 1978 Whitey and his team submitted their first offer of R1 million. It was not accepted. A month later they increased the offer to R2,4 million. Half Price Stores’ creditors were still considering this bid when Scotts Stores from Durban unexpectedly entered the picture. While smaller than Pep, Scotts was still one of the country’s leading retailers and intent on expansion through diversification. Half Price Stores was the perfect way in which to achieve their goal. This was the start of one of the longest and toughest takeover battles in South Africa. Pep and Scotts would repeatedly try to outmanoeuvre each other and up their bids for Half Price Stores.

Some of the largest creditors were Philip Frame’s Consolidated Textile Mills and Anglo African Shipping. Whitey then drew a line in the sand: ‘I went to see them and said, don’t waste everyone’s time. Tell me now whether you will support me or Scotts, but I’m not going to plod on like this.’ A report in the Cape Times referred to a ‘secret deal’ with the liquidators, but Whitey denied this. In the event, Pep did secure the support of Anglo African Shipping, to whom Half Price owed the most money, as well as that of most of the other creditors of its subsidiaries. Scotts Stores did not increase their bid, but a group of employees of Half Price Stores – with Ashby’s support – opposed Pep’s bid. This process reached a stalemate. On 20 July 1978 the Cape Town Supreme Court had to decide whether or not Pep’s last offer should be accepted. Scotts, who had earlier thrown in the towel, were now up for the contest again and once more increased their bid. Both Pep and Scotts got back into the ring and did their utmost to outwit each other. The offer on the table was raised several times, which prompted Judge Gerald Friedman to protest that he was not an auctioneer. ‘But then it turned into an auction anyway,’ Fouché recounts. Both companies eventually offered 45 cents in the rand for Half Price. Owing to different stock valuations Pep’s total offer was slightly more than that of Scotts, and the bid conditions also differed in some respects.

‘Dave Scott from Scotts Stores then went to Renier,’ Whitey relates, ‘and wrote down on a piece of paper what he was prepared to pay for Half Price, plus a proposal for a deal from which both he and we would gain.’ It worked like this: He would offer 65 cents in the rand – 20 cents more than the bid that was on the table at that point. Pep would pay him half of the difference – in other words, ten cents in the rand – and he would walk away.

‘They came to me with this, and I said: “There is no way I’m getting involved in a deal of this kind. Because the creditors and the families that worked for Half Price were entitled to get the maximum the market was prepared to pay. So, I’m not going to enrich Scott at the expense of others. We’re bidding against Scott cent for cent, and he has to take our punches.” Renier conveyed the message, and the next day they walked away.’ The court also found that the objections of the group of employees were invalid, and ultimately Pep emerged victorious from the contest.

The final purchase price was about R3 million, much higher than the R1 million Pep had offered only a month before. But the battle was over, and Pep could look ahead knowing that one of its most troublesome rivals was now in its stable.

Half Price Stores was initially still operated under its own brand, but was eventually fully integrated into Pep Stores and all the outlets were converted into Pep branches. As Whitey and his team had promised, they turned around the Half Price stores that had not been closed, and by December 1978 they had returned to profitability. ‘But I still had to sell rice for a while, as it kept arriving on the ships from India!’

***

In 1978, after a four-year break, Van Rooyen returned in full force. The disagreements between him and Whitey intensified. ‘He felt much of what I’d done he would perhaps have done differently, and he then tried to overturn it,’ says Whitey. ‘Although we always remained friends, relations between us were more strained for a while. He treated me like a son and we were very attached to each other, but people could see at that stage that we were quarrelling, and that we didn’t see eye to eye on a number of things. ’

Whitey realised something had to happen. ‘And at a point I told him I couldn’t work with him any longer, that I had a lot of respect for him, but that he and I were now going to create bad blood between us. I didn’t feel like it any more. It was his company that he had started, and he took the final decisions, and everything I’d done he now wanted to reverse.’ Whitey wanted to resign in order to preserve the relationship between him and Van Rooyen. He admits that Van Rooyen had an ‘enormous influence’ on his life. ‘He taught me how to paint, if I can put it like that. He taught me the art of retailing, and that probably helped me the best.’

For a considerable time, however, Whitey had been thinking of going into fast-moving consumer goods such as food retail, and he and Van Rooyen discussed this. Whitey was keen on starting a new venture, and Van Rooyen encouraged his entrepreneurial zeal.10 ‘He said he wanted to back me, and his proposal was that we do it together. The plan was to be partners – I help him, and he helps me.’ Whitey began scouting around for opportunities and did his homework about the retail food industry. He went to Germany and Italy and eventually collaborated with the Italian company PAM Supermercati with a view to bringing a low-cost, limited-assortment business similar to Aldi or Lidl to South Africa.

Whitey and Pep were on the verge of entering into a partnership in this regard when luck intervened. Back home in South Africa, a golden opportunity would present itself. A tiny company in the Cape Peninsula came on to the market. The Rogut family had fallen out among themselves and wanted to sell their business. An acquaintance phoned Whitey and said: ‘There are eight stores for sale here with the name Shoprite. Are you interested?’ The blank canvas of Whitey’s masterpiece lay before him. DM/ ML

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

Comments - Please login in order to comment.