MERE IMMORTALS

Grytviken, where a polar hero’s remains rest amid an ecosystem in recovery

Revered polar explorer Ernest Shackleton’s grave on the island of South Georgia is luring hundreds more tourists since the discovery in March this year of his sunken ship, Endurance, in Antarctica’s Weddell Sea. But the hero’s final resting place is also a stark reminder of man’s cruel indifference to our natural world.

Light snow is falling as we trudge up the hill to the small, fenced graveyard at Grytviken, South Georgia, where Ernest Shackleton lies buried. The sky is the colour of Pinotage, the tussock grass slippery as we follow a route that zigzags over muddy bog and around slumbering fur seals.

We’re thrilled to see these fat, doe-eyed sea mammals because during the late 19th and early 20th centuries they, like whales, were hunted almost to extinction. Since the whaling industry’s collapse here in the mid-1960s (there were too few whales left to hunt), seal numbers have recovered to an estimated four to six million and many hundreds now make Grytviken their home.

Fur seal sitting on the shore. Image: Toni Younghusband

Fur seal. Image: Toni Younghusband

It strikes me as woeful that Shackleton should be buried here: an extraordinary hero with a deep love for this wild region laid to rest where thousands of animals were butchered with little care for the impact their decline had on the ecology of our seas. But we know that South Georgia played an almost mythological role in Shackleton’s Endurance expedition and the island was very dear to him. His wife determined that his body should lie at Grytviken.

Shackleton’s rough stone monument lies top left of the cemetery, engraved with a line from this Robert Browning poem: “I hold that a man should strive to his uttermost for his life’s set prize.” Though he never did reach the South Pole, Shackleton is widely regarded as one of the world’s greatest polar explorers, celebrated for his leadership style, his courage and tenacity, and his charisma. He died of a heart attack shortly before attempting his fourth journey to the Pole.

Ernest Shackleton’s grave. Image: Toni Younghusband

The grave of Irish Antarctic explorer Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton, erected in a whalers’ graveyard on the Island of South Georgia, circa 1922. He returned to the island on the ‘Quest’ a few years after his Antarctic expedition, and died there of a heart attack. Image: Hulton Archive / Getty Images

Alongside Shackleton’s grave is a stone plaque set in the grass. It covers the spot where the ashes of Frank Wild, Shackleton’s Endurance expedition second-in-command, are buried. Wild participated in five Antarctic expeditions and died in Klerksdorp, South Africa, in 1939 but it took him more than 70 years to join his compatriot. His ashes lay forgotten in a vault at Braamfontein Cemetery until discovered in 2011 by a historian and, in accordance with Wild’s deathbed wish, were finally laid to rest alongside the man he called “The Boss”.

This tiny graveyard, the burial ground of whalers and sealers also, has become one of the Antarctic’s most visited tourist attractions since the discovery of the Endurance nearly 107 years after she was crushed by ice. There is still an almost religious veneration of Shackleton and his like: men whose extraordinary bravery and perseverance in the face of impossible odds remind us of the frailty — and strength — of humankind. Those of us standing in this graveyard, snow dusting our jackets, are silent, as though speaking might extinguish that flame of valour.

Portrait of Irish Antarctic explorer Lieutenant Ernest Henry Shackleton (1874-1922), junior officer with Scott’s National Antarctic Expedition 1901-1903. circa 1910. Image: Hulton Archive / Getty Images

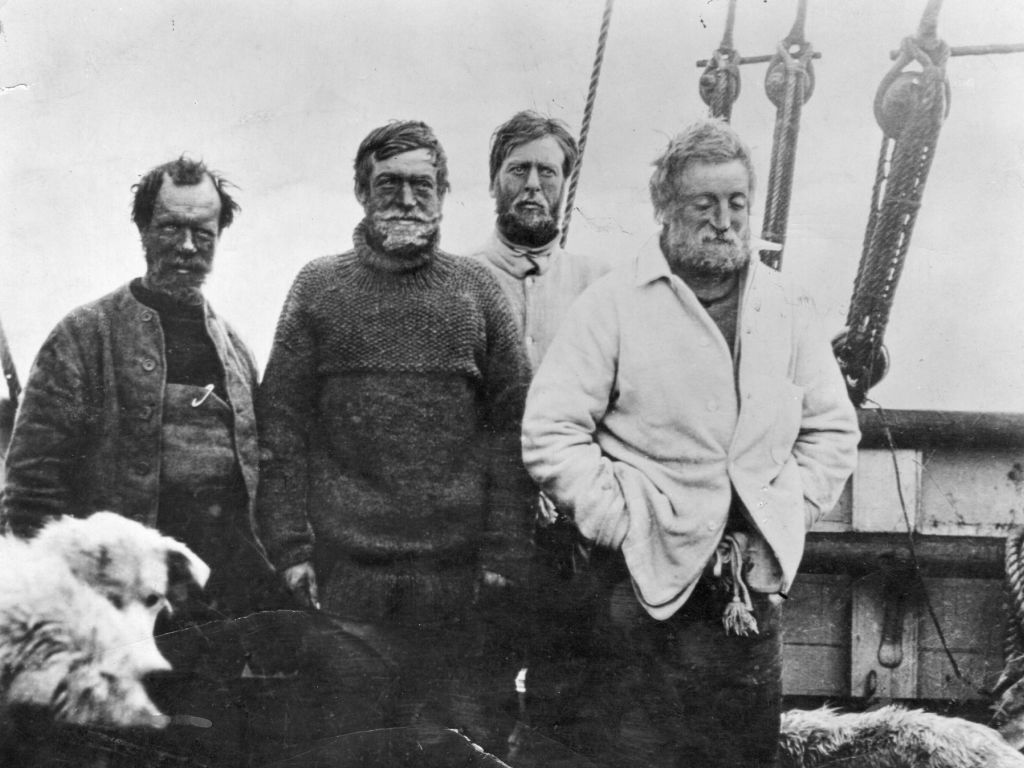

Irish explorer Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton, in the southern party on board the vessel ‘Nimrod’, on their return voyage from the British Antarctic Expedition in 1909 after reaching a point 97 miles from the South Pole, a record at the time. Image: Spencer Arnold Collection / Hulton Archive / Getty Images

The ‘HMS Endurance’ caught in the ice in the Weddell Sea of the Antarctic during Sir Ernest Shackleton’s Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, circa 1915. Image: Hulton Archive / Getty Images

Members of an expedition team led by Irish explorer Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton pull one of their lifeboats across the snow in the Antarctic, following the loss of the ‘Endurance’. Image: Hulton Archive / Getty Images

It’s a weird place, Grytviken. At one corner, the neatly tended graveyard where Shackleton and Wild are remembered in awe, the remainder of the town given over to an industry that almost ended the existence of the largest animals on Earth.

Whalers at Grytviken. Image: Toni Younghusband

Lying in the South Atlantic roughly 2,000km due east of the bottom boot-tip of Argentina, Grytviken was in continuous operation as a whaling station for 58 years. In its heyday, up to 500 whalers and their families lived here, and their church and cinema still stand, though their homes have been destroyed by ice and snow. Rusted boiling pots several storeys high still dominate the town centre above the volcanic beach where the whaling ships — now ghostly wrecks resting on the black sand — deposited their cargo. Whales were harpooned at sea, then winched ashore to die with chains thicker than a strong man’s bicep. In the end, the men would flense (strip) the skin of the whale and separate the blubber from the meat. It was dirty, smelly, intensely physical work performed primarily by men who could find work nowhere else. Many spoke about this place as “hell”.

Blubber vats in Grytviken. Image: Toni Younghusband

King Penguins. Image: Toni Younghusband

Humans living here now number between eight and 30; employees of the South Georgia Heritage Trust who run the museum, British military, and customs officials. Scientists camp at nearby King Edward Point. Seals dominate the island (95% of the world’s fur seals live on South Georgia), and in its surrounding waters whales once again compete for krill with more than two million macaroni, king, gentoo and chinstrap penguins.

South Georgia is a global rarity; an ecosystem in recovery which must act as a reminder to us all of what can be done to save our natural world. Shackleton would have liked that. DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

I sailed there from the Falklands in 2017 on Pelagic Australis, Skip Novak’s then expedition yacht. We took 3 scientists, 2 from the Climate Change Institute from the University of Maine, to collect ice core samples from one of the glaciers, for research and carbon dating. Spent a month on the island including hiking the Shackleton traverse. A truly humbling experience.

Very evocative piece on an amazing place. I trust you all drank an appropriate toast to ‘The Boss’ at the gravesite?