BOOK OP-ED

Like a cork upon a tide — The enduring relevance of James Joyce as ‘Ulysses’ turns 100

Ulysses had a reputation for being difficult, so students studiously avoided it. Joyce was ahead of his time, which is a double-edged sword. However much he enjoyed the kudos attached to being a trailblazer, he certainly could have done with more popular acclaim and royalties.

I’d just inserted a blank page into my typewriter and was staring at it, trying to think of something original — actually, anything at all — to say about TS Eliot’s “Four Quartets”, when I heard a muffled shout — more like the bellow of a wounded steer. My student digs were below my landlord’s living room and he and his wife were clearly no longer living in a state of connubial bliss. The bellow was followed by a shrill, feminine riposte. What had she just said? Then there was an inarticulate eruption and something heavy — a piece of furniture? — crashed to the floor above my head. I heard the tinkling sound of something smashing. A wine glass against the mantelpiece perhaps? And a door slamming. Then silence.

When I saw my splenetic landlord or his pulchritudinous wife on campus, we behaved as if I hadn’t heard anything. Well, in a sense I hadn’t. But I sided with her. Obviously. I mean, Glen was beautiful. And sad. Probably misunderstood. What if she came down to my room in need of comforting? That was a heart-stopping prospect for a single guy with no one besides TS Eliot for company. On the other hand, her husband was capable of violence if the way he manhandled the furniture was anything to go by.

Late one night, there was a knock at my door.

“Who is it?”

“Me.”

“Glen?”

“Can I come in?”

What was I letting myself in for? I opened the door. She was standing there, looking sensational. She was also holding out a small stack of books. “I’m leaving him,” she said, “and I thought you might like these.” Then she gave me a brave smile and turned on her exquisite heel. I glanced at the book on top of the pile. Glen was leaving her husband and she wasn’t taking James Joyce with her.

I’d almost completed English Honours and I still hadn’t read Ulysses. In my defence, I’m fairly confident no one else doing Honours at Rhodes that year had read it either. It had been a set work for English III but had been removed the year before I got there. Ulysses had a reputation for being difficult, so students studiously avoided it. Faced with this rising tide of philistinism, champions of the novel on the academic staff conceded defeat and ruefully took it off the syllabus.

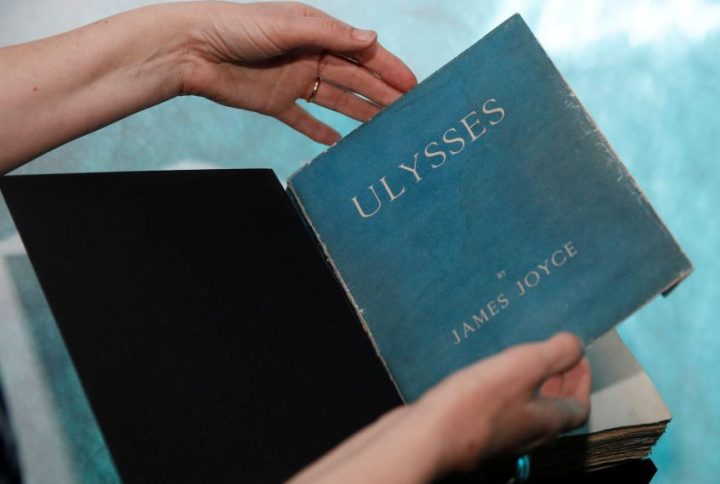

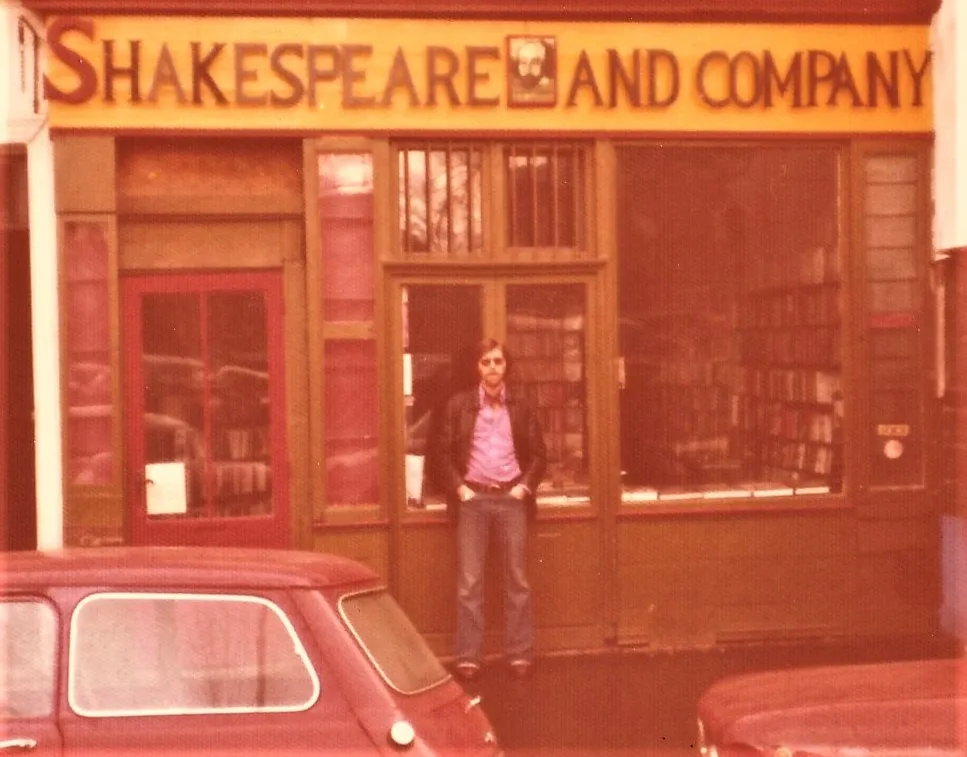

The copy of ‘Ulysses’ given to the author by Glen. Image: Anthony Akerman

I was intrigued by Joyce and had read A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, in which he’d written, “When the soul of a man is born in this country there are nets flung at it to hold it back from flight. … I shall try to fly by those nets.” I could relate, given the way I felt about South Africa. He left Ireland when he was my age and spent the rest of his life in exile.

At the end of my undistinguished academic career, I found myself back home in stiflingly parochial Hillcrest living with Mum and Dad, who must have wished I’d come out of university with a qualification rather than a so-called education. I’d made an appointment to sit the test for a public driving permit and planned to drive Eagle Taxis until I’d saved enough to go to theatre school in England. My test was two weeks away, which gave me enough time to learn all of Durban’s street names — and read Ulysses.

I knew it was something like a modern-day take on Homer’s Odyssey — a story I’d loved as a schoolboy — and that the action took place in Dublin on a single day. I sat down on the sofa, opened my Penguin edition and saw Glen’s name in black italics. I turned to the end. It was 704 pages and at the bottom of the final page were the words — Trieste-Zürich-Paris, 1914-1921. It had taken Joyce seven years to write and he’d done so in three different cities — cities I could only dream of visiting. 704 pages? I read slowly because — like Hollywood producers — my lips move slowly. So I gave myself a week. I calculated 100 pages of Ulysses a day was doable.

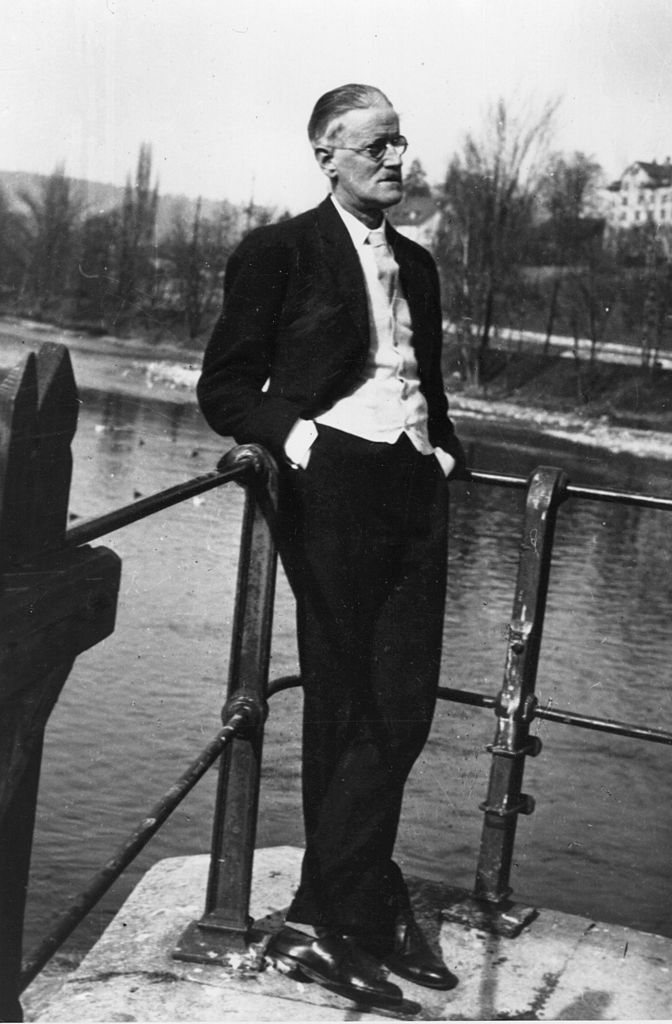

Irish novelist, short-story writer and poet James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (1882 – 1941) in Zurich. Image: Hulton Archive / Getty Images

Mum prided herself on being a no-nonsense person and had little sympathy for my liberal ideas, long hair and bad language. She set her alarm clock for 3:30 in the morning, got up and did housework, then walked down to the village where she took shorthand and typed letters for a firm of solicitors until lunchtime, after which she gardened or played tennis. She was an avid reader of novels — historical romances — but felt the appropriate time and place to do so was in bed before you went to sleep. I could think of more exciting things to do in bed but they remained, to quote from TS Eliot’s “Four Quartets”, “a perpetual possibility / Only in a world of speculation.”

Every time Mum walked past the open door and saw me sprawled decadently on the sofa like a latter-day Oscar Wilde, her irritation level went up a notch. Probably on day three — when Gertie MacDowell was exposing her legs and undergarments to an aroused Leopold Bloom on Sandymount Strand — Mum could no longer contain her exasperation.

“Don’t you have anything better to do?”

“I’m reading fucking Ulysses!”

“For goodness’ sake, do something useful.”

I don’t think I could have participated in an erudite discussion or written a scholarly paper after I’d put the book down, but I found it absorbing and fascinating. And, yes, I enjoyed it. I also found it entertaining and funny. It occurred to me that the English Department could have done a much better job of marketing it to students. Apart from breaking new ground at the time of its publication, its undeniable literary qualities, its cavalcade of memorable characters and its being a great story inventively told, Ulysses was a novel that described things our moral guardians would rather have left undescribed — and often in language that would have fallen foul of the Publications and Entertainment Act, 1963.

There are, for example, eleven occurrences of the root word “fuck”, or inflections of the word, at a time when one was enough to have had it declared “undesirable”. I speak from personal experience, because eleven years later I received a letter from the Director of Publications listing my use of that venerable Anglo-Saxon word as one of the reasons why my play Somewhere on the Border was “offensive to the reasonable and balanced reader” and could not be “distributed in the Republic of South Africa”. If you tell South Africans they can’t do something, they’ll usually want to do it. So had the academic staff put it about that Ulysses had slipped past the censor unnoticed and it was simply a matter of time before a meddlesome dominee lodged a complaint and it was banned, it may have created a sense of excitement and urgency among English III students. Well, maybe not. After all, nothing would induce Nora Joyce to read her husband’s books.

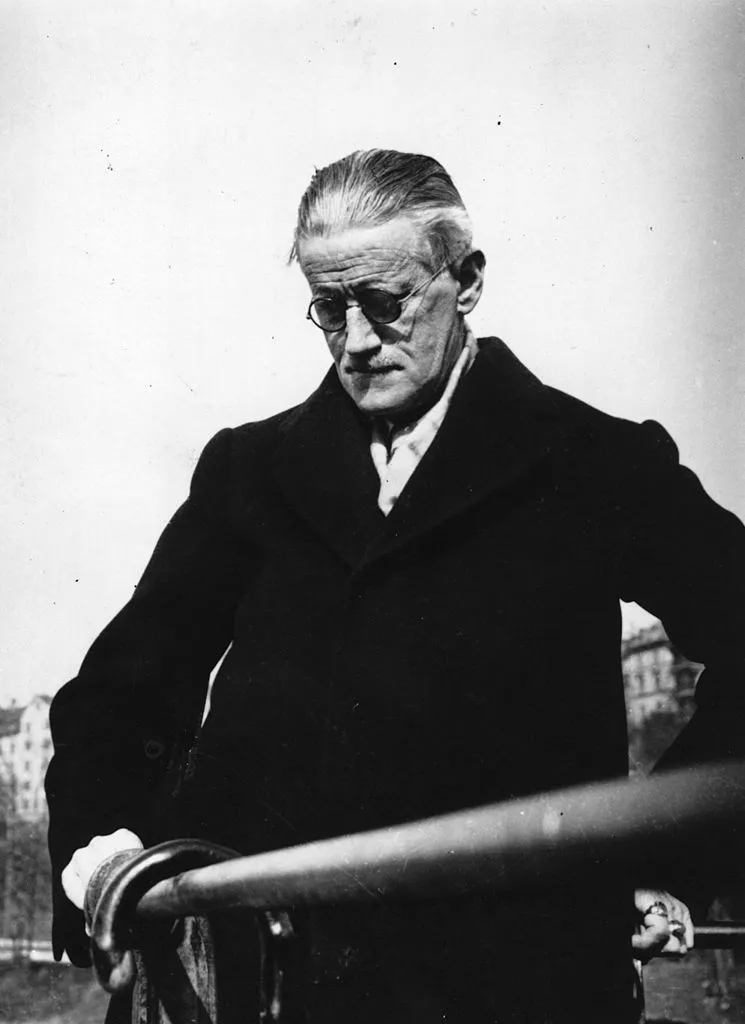

Irish novelist and short story writer James Joyce. Image: Hulton Archive / Getty Images

Irish writer James Joyce (1882 – 1941) with his wife Nora, left, and Mrs C Fredion in 1925. Image: Hulton Archive / Getty Images

***

Shortly after I arrived in Britain, I invested in a state-of-the-art portable radio/cassette recorder. It worked on mains and batteries, had a built-in microphone and you could also record directly from the radio. There were many arts programmes on BBC, which was a refreshing change as South Africa had very little arts coverage then — and has even less now. During my first winter in Bristol, while I was feeding 20p pieces to the gas heater in my dingy digs, I was just in time to press the record button for a programme called Portrait of the Artist, originally broadcast on 16 June 1950. It was the story of James Joyce’s life told by his family and friends. As I hadn’t yet read Richard Ellmann’s biography, most of it was new to me.

16 June 1904 — a date now celebrated in Dublin as Bloomsday — was the day Joyce and Nora Barnacle fell in love and the day on which the action in Ulysses unfolds. Nora was a simple country girl from Galway, but she agreed to elope with Joyce without getting married. They set off for Zürich where he wanted to write and promised he could support them by teaching English at a Berlitz School.

As there was no vacancy in Zürich, they made a temporary move to Trieste — then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire — where he did find work at the Berlitz School and where they remained for the next decade. While there he completed his short story collection Dubliners, his novel Portrait and his play Exiles. And, of course, he also began work on Ulysses.

Initially, he had little or no success getting his work published. Dubliners, for example, was submitted 18 times to 15 publishers between 1905 and publication in 1914. The perennial problem was English printers refusing to print his work. In 1913, WB Yeats sent one of Joyce’s poems to Ezra Pound who was putting together an anthology of Imagist verse. Pound was taken with the poem and wrote to Joyce, who then sent him the first chapter of the unfinished Portrait.

Pound was so impressed that he arranged with Harriet Shaw Weaver, a wealthy English feminist and editor of the influential Egoist, to have the novel serialised in her magazine. The first instalment appeared on 2 February 1914, the highly superstitious Joyce’s 32nd birthday. Weaver was one of several women who helped and sustained Joyce’s literary career. When she came into an inheritance she didn’t need, she arranged with her solicitors to make regular, and initially anonymous, donations to Joyce who was as often chronically impecunious as he was incurably given to splendid extravagance. Jane Lidderdale, Weaver’s biographer, claims that between 1917 and 1924 Weaver contributed over £21,000 — which today would be worth approximately £1,250,000 or R25,500,000.

Harriet Shaw Weaver in 1907. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Joyce and his family — by now he had a son Giorgio and daughter Lucia — moved from Trieste to Zurich in June 1915. Presumably, their departure was hastened after the Austrians arrested his brother Stanislaus as a subversive in December 1914. While in Zürich he befriended Frank Budgen, an English painter, who became a sounding board during the writing of Ulysses and who would, in 1934, publish James Joyce and the Making of Ulysses — another book in the pile given to me by Glen.

One evening walking on the Bahnhofstrasse, Budgen asked Joyce how work on Ulysses was progressing. Joyce said he’d been working hard on it all day. “Does that mean,” asked Budgen, “that you have written a great deal?” “Two sentences,” replied Joyce. Two sentences? If James Joyce could spend a day on two sentences, I’d done pretty well reading 100 pages a day.

As I emerged from my teens, writers supplanted pop singers in my personal pantheon and I was intrigued by what I read about their writing habits and rituals. Unlike Joyce, Graham Greene wrote 500 words a day. So did Ernest Hemingway, although he wrote standing up with his typewriter on a chest-high reading board. Virginia Woolf also wrote standing at a lectern, but she wrote in longhand using variously purple, green and blue ink. According to his sister Eileen, Joyce wrote lying across the bed on his stomach using a large blue pencil. If Mum had walked past his open bedroom door and seen him in that recumbent posture, she would have told him to do something useful.

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

In April 1918, the first episode of Ulysses was published in the Little Review in Chicago. By January 1919, numbers of the magazine were being confiscated. Confiscation meant burning. Both editors were eventually prosecuted, found guilty of publishing obscenity and each fined $50. This legal precedent effectively meant that if Ulysses were to be published in the United States it would inevitably be banned. Although episodes had also been published in the Egoist, Weaver gave up plans to publish the book in England as printers would not risk it. No doubt with bittersweet jocularity, Joyce remarked to Pound, “No country outside of Africa will print it.”

***

In July 1920, the Joyce family stopped off in Paris en route to London and Ireland. An intended week-long visit was extended for almost 20 years. Pound immediately introduced Joyce to his circle of close friends, which included Adrienne Monnier and Sylvia Beach. Monnier was the owner of the renowned bookshop and lending library, La Maison des Amis des Livres (The House of Friends of Books) on Rue de l’Odéon, which was also a rendezvous where young writers gathered to meet famous French authors.

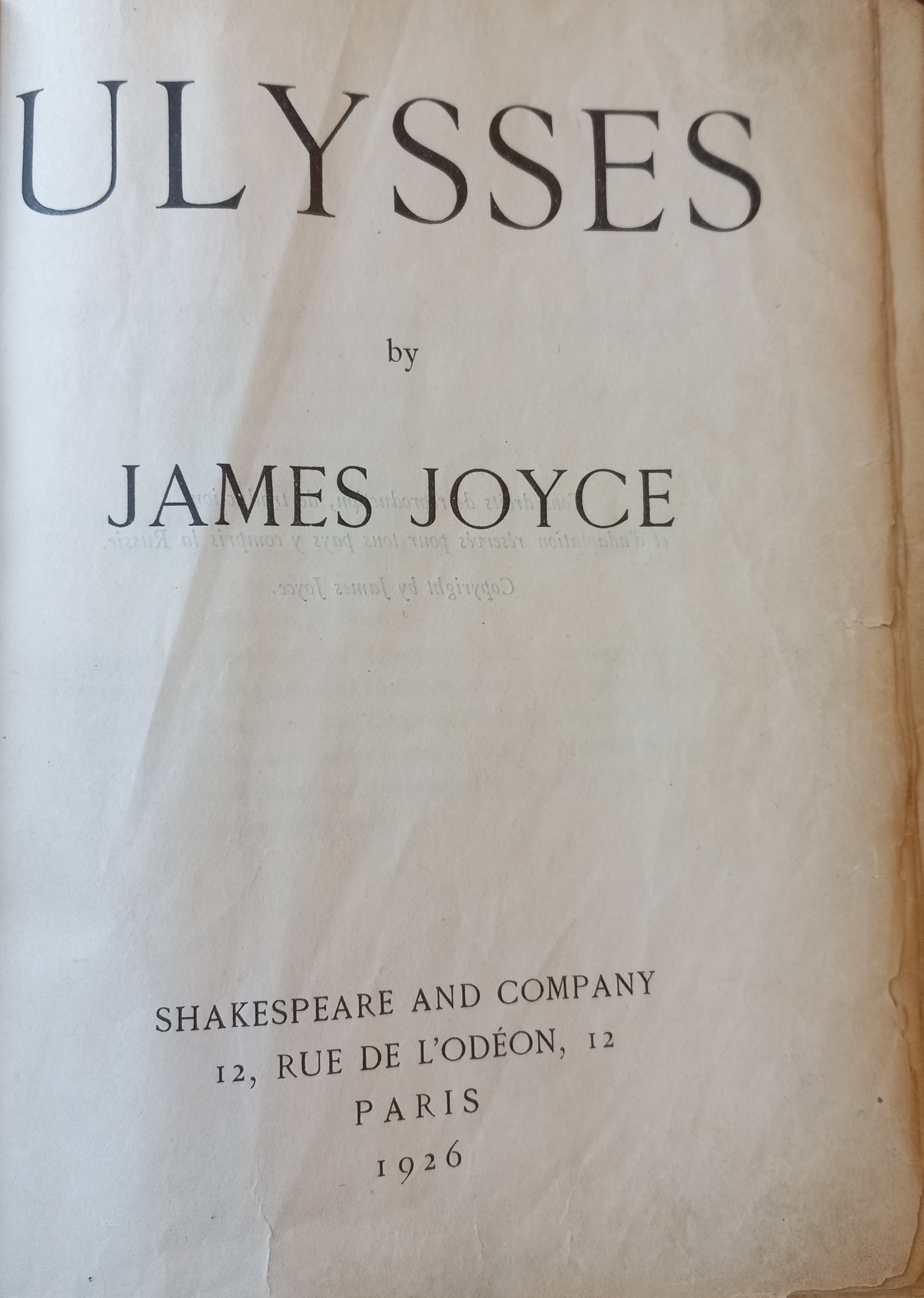

In 1917, the newly arrived daughter of a Princeton Presbyterian minister visited this bookshop and was inspired to open her own. Two years later and with encouragement from Monnier, Beach opened Shakespeare and Company specifically to serve the cause of English and American literature. Her patrons included Hemingway, Scott Fitzgerald, Sherwood Anderson, André Gide, Gertrude Stein and DH Lawrence. Most expatriate writers used her bookshop as their Parisian postal address.

Sylvia Beach (1887 – 1962), the unofficial historian of ‘The Lost Generation’ watches composer George Antheil (1900 – 1959) climbing up to a second-floor window of her bookshop, ‘Shakespeare and Company’, 12 Rue de l’Odeon, Paris. She was the first bookseller to sell copies of James Joyce’s ‘Ulysses’ which was printed in France. Image: Paul Almasy / Three Lions/Getty Images

Anthony Akerman in Paris, December 1974, outside the bookshop, ‘Shakespeare and Company’. Image: Anthony Akerman

A year into his stay in Paris and disheartened by the news from New York and London, Joyce visited Shakespeare and Company. “Miss Beach,” he said, “my book will never come out now.” “Mr Joyce,” she said, “would you let Shakespeare and Company have the honour of bringing out your Ulysses?” Apparently, Joyce was as startled when he heard her proposal as she’d been when making it. The 34-year-old Beach had never published anything before and Joyce warned her that no one would buy his book. She was prepared to risk it and he accepted her offer without hesitation.

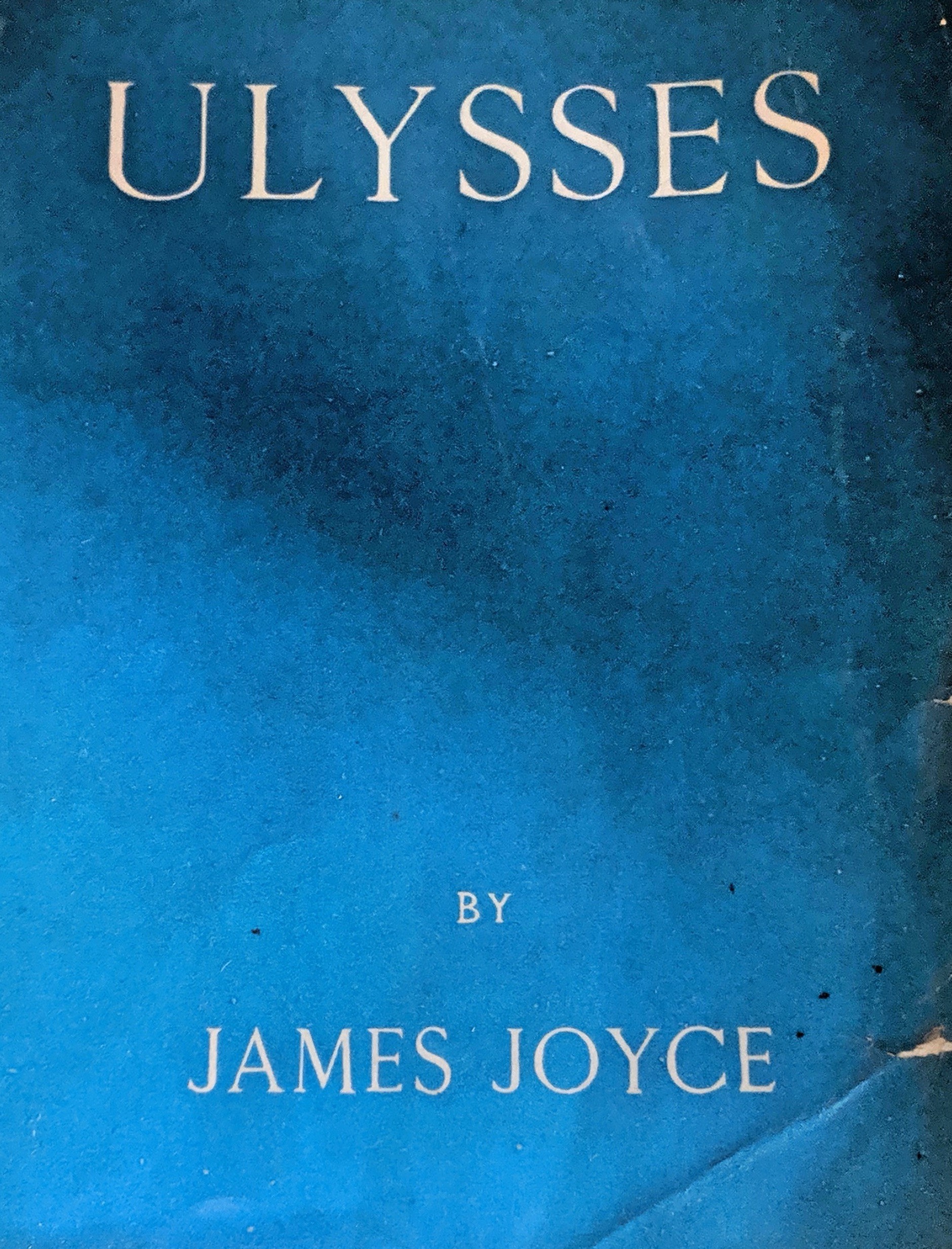

Beach was assisted by Weaver in obtaining advance subscriptions to purchase the first edition of 1,000 numbered copies. She also found a printer in Dijon who was willing to proceed without an advance and no one objected to the “language” in the book — and, presumably, not only because they neither read nor spoke English. The downside was that there were said to have been over 2,000 typographical errors and subsequent editions had to be published with an errata sheet. Joyce had wanted the book to appear on his 40th birthday but there was a delay. In the event, Beach ensured the printer sent two advance copies to Paris which she delivered to Joyce on 2 February 1922. He sent copy No 1 to Weaver who, later that year, was to publish 2,000 numbered copies in England.

First edition of Ulysses in Greek colours – white letters on a blue background. Image: Anthony Akerman

It’s fair to say it had a mixed reception in fiercely jealous literary circles. Some were envious, some dismissive and others impressed. Gertrude Stein felt people liked the book because it was “incomprehensible”, the patrician Virginia Woolf sneered that it was “underbred” and “the book of a self-taught working man,” but Yeats described it as, “a work perhaps of genius” and Hemingway said, “Joyce has a most goddamn wonderful book.”

Opinions among the temporal powers were less divided than among literati. In 1922, 500 copies were burnt by the New York Post Office Authorities. The British Director of Public Prosecutions, Sir Archibald Bodkin — who admitted he’d only read pages 690 to 732 — pronounced it a “filthy book” and stated that it should “not be allowed to be imported into the country.” In 1923, Customs Authorities in Folkestone seized 499 copies and the novel remained banned until 1936.

Although said in jest, Joyce didn’t know South Africa very well if he thought Ulysses could have been printed here. On the other hand, I’ve found no evidence that the UK ban extended to the Union and Rand Club has a copy of the 8th printing of the Shakespeare and Company edition (May 1926).

The pages that offended Sir Archibald Bodkin would have been in the final Penelope Episode, often referred to as Molly Bloom’s soliloquy or monologue. TS Eliot took a different view and was clearly overawed when he said, “How could anyone write again after achieving the immense prodigy of the last chapter?” With her husband asleep next to her, Molly’s freewheeling and sensual ruminations contrast with the masculine voices that have dominated the narrative up to that point. Unlike Homer’s Penelope, who spent 20 chaste years fending off suitors and waiting for Odysseus to return, Molly spent the afternoon in her marital bed with her lover Blazes Boylan. Had Glen perhaps had her own Blazes Boylan? Had her life imitated Joyce’s art? Could that have been what triggered the violent altercations I strained my ears to follow? Should I read anything into her parting gift of Ulysses and five other books about Joyce?

Molly Bloom’s monologue is a tour de force, a stream-of-consciousness that mimics and approximates our human thought processes, the way we think rather than the formal way we speak, in eight largely unpunctuated sentences, the longest of which was 4,391 words — until recently the longest printed sentence in the English language. It invites performance and is both a gift and a daunting prospect for any actress. In 2009, writer-director Nicky Rebelo staged his own adaptation at the National Arts Festival. Jennifer Steyn as Molly Bloom matched the brilliance of Joyce’s text and together actor and director took audiences on a journey that was spellbinding, insightful, by turns deeply affecting and funny. When I saw it at Rand Club, the 1926 edition of Ulysses was on display for audiences to see.

Jennifer Steyn as Molly Bloom. Image: Nicky Rebelo

The Rand Club copy of ‘Ulysses’. Image: Alicia Thompson

Joyce was ahead of his time, which is a double-edged sword. However much he enjoyed the kudos attached to being a trailblazer, he certainly could have done with more popular acclaim and royalties emanating from increased sales. In 1998 the novel first printed by French printers was selected by a panel of scholars and writers on the editorial board of the Modern Library — a division of Random House — as the best English-language novel of the century. It may not be everyone’s tankard of Guinness, but it’s a classic that can no longer be studiously avoided by students of literature.

***

Homer was traditionally portrayed as a blind poet and it’s a cruel irony that Joyce’s life was a constant struggle against failing eyesight. Over the years he underwent numerous operations for iritis, glaucoma and cataracts at a time when ophthalmic surgery was in its infancy. He wore thick lenses and had to read with a magnifying glass. During the last 17 years of his life, when he was working on what came to be called Finnegans Wake, his daughter Lucia described how she saw him in tears because he couldn’t read the words he’d written. Another source of immense anguish in Joyce’s life came when Lucia was diagnosed with schizophrenia and confined to a psychiatric hospital.

A year after his last book was published, German troops marched into Paris. Joyce and his family had been making plans to return to Switzerland but their departure was delayed by the refusal of the authorities in Vichy France to allow Lucia to accompany them. They had to leave her behind and eventually crossed the border into neutral Switzerland on 17 December 1940. In mid-January, Joyce was rushed to hospital with a perforated ulcer, where he died two days later at the age of 58.

It was snowing the day his coffin was carried up the hill to Zürich’s Fluntern Cemetery. After a few speeches in the Friedhofkapelle, the family and several friends gathered around the open grave. As the pallbearers began lowering the coffin, one of them was approached by an ancient man who asked, “Who is buried here?” He answered, “Herr Choice.” “Who is it?” repeated his interlocutor. By then he realised the old man was hard of hearing and so he shouted, “HERR CHOICE” as the coffin of one of Ireland’s greatest writers reached its final resting place.

Nora continued to live in Zürich until her death 10 years later. She was one of the women who made it possible for Joyce to be the writer he became. Unlike Weaver, Monnier and Beach her support wasn’t on a literary level, but she made a home for her Jim, had his children out of wedlock, cohabited until 1931 when he married her so she and the children would inherit his copyright, mothered him and looked after him. When asked if she was Molly Bloom, she replied, “I’m not — she was much fatter.” Although she never read her husband’s books, when a journalist asked what she thought of Gide she replied, “Sure, if you’ve been married to the greatest writer in the world, you don’t remember all the little fellows.”

***

When I first listened to the account of the Swiss pallbearer shouting “Mr Choice” as James Joyce took his final bow, I understood the story was told in the knowledge that it would have amused the man himself. All those years ago, while feeding 20p pieces to the gas heater in my dingy Bristol digs, I promised myself I’d one day visit his grave.

Anthony Akerman at James Joyce’s grave, 2007. Image: André Hattingh

My sister Gill moved to Switzerland in 1979 but whenever I visited her family — or was passing through en route from Amsterdam to Italy — there just never seemed to be time. Besides, no one else knew who the hell James Joyce was. When I told them, they were even less interested. 15 years ago we went to Switzerland for my nephew’s wedding and I decided a visit to Joyce’s grave — which I by then knew was in Fluntern Cemetery — was non-negotiable.

Gill and her boyfriend Kevin were living in Cape Town at the time. Kevin worked for a company that sold engine parts. He was also a confident and excellent driver. I told him why I wanted to go to the cemetery on the hill next to the Zürich Zoo and he volunteered to do the driving. It didn’t take us long to find the grave, clearly marked by Milton Hebald’s statue of Joyce.

“Incredible,” said Kevin, “to think this is where they buried Jack Daniels.” DM/ ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Fabulous article, thank you.

Wonderful interweaving of history and personal insights. I love the passion.