LESSONS FROM MY FATHER

Zingisa Worthington Ndungane – role-modelling perseverance and keeping family bonds strong

Odwa Ndungane played for the Sharks between 2005 and 2017. Akona played for the Bulls between 2005 and 2015, and was a member of the World Cup-winning squad of 2007; both of them represented the Springboks. This is the story of their father’s powerful and long-lasting influence.

Our father, Zingisa Ndungane, was born in a village called Gungululu in rural Eastern Cape. His name, Zingisa, means “Persevere” – and did he live up to his name! He taught us so much about perseverance, lessons which, at the time, we didn’t realise we were learning. Those lessons stood us in good stead in the years to come. Had we not had our father role-modelling perseverance, well, who knows? Our rugby careers would probably not have turned out as they did.

From when our dad was very young his parents had to travel considerable distances to get to work, and as a result Dad and his twin brother were taken to live with their Makhulu (his grandmother, our great-grandmother) in Corane, a village about 10km from Mthatha.

In effect, their Makhulu raised them. She was a strict woman, and it was sometimes difficult for Dad and his brother to have a voice. Nevertheless, she did a great job raising them, giving them the grounding that set them up for life. Dad didn’t tell us much about his upbringing, but when he did tell us stories occasionally, he always spoke fondly of her.

Although we know little of Dad’s childhood, we do know it was not easy. There were none of the luxuries of life. None at all. Life was challenging, but was much more so for his friends in the village, many of whom often went to bed hungry. Our father was a bit more fortunate: his Makhulu at least had some livestock, so they did okay compared with his peers.

One story he often relayed was how his Makhulu would send him to do errands, which required waking up at 4am and walking long distances. One such errand was fetching horses or cows to plough on the farm. Some of the villages were as far as 40km apart, which is quite a distance to send a young boy, but in those days it was common practice, and villages were safe for a youngster to pass through.

Dad and his sibling were expected to do many chores to help the family and the community in which he lived. Feeding the livestock, herding and often getting up well before dawn to work on the land were just a few.

But there was also some time for games. As was customary in rural areas – and still is today – children used their rich imagination and made up many different games, often using whatever they could find as “props”. They also played traditional games, such as stick-fighting. All of these games had been passed down over many years, from generation to generation.

That was the life our Dad lived.

***

Having been cared for and nurtured by his Makhulu was to prove formative. It was she who instilled in him – and his brother – strong values which stayed with him all his life. One thing Dad told us was that she taught him about respect, and the need to keep strong ties with family and one’s community. That was to become a key aspect of our father’s parenting. His emphasis on respecting anyone and everyone we encountered, and on the important need to keep family bonds strong, is something we’ll always remember about him, and for which we’ll always be grateful.

Akona Ndungane with Odwa Ndungane of the Sharks during the Absa Currie Cup match between The Sharks and Vodacom Blue Bulls at Growthpoint Kings Park on August 31, 2013 in Durban, South Africa. Image: Steve Haag / Gallo Images

During our childhood and into our teens, Dad was a strict, firm father. You could say he was traditional in the way he parented, which was fairly typical of fathers of his time. He was old-school; it would be an exaggeration to say that he ruled with an iron fist, he wasn’t like that. But, his position of authority in the family was clear. The environment in which he grew up, and the one in which he fathered us, was such that one couldn’t – one didn’t – question authority. As a child, one didn’t ask a lot of questions. It would be seen as disrespectful to question an instruction, or a decision he made.

Dad commanded respect. It wasn’t a case of demanding respect; it wasn’t like, “I’m in charge here, and you must respect me”. Deep down, we just knew: he knows what’s good for us. We appreciated that.

On his firmness and the respect we had for our dad, two memories stick out. At a family dinner one afternoon, our younger brother, Sibulele, started to pick at his food with his knife. Dad told him: “Sibulele, stop that.” Out of respect, Sibulele did so, immediately. One day, when we were much older, Sibu jokingly questioned Dad on this – the picking at food with the knife, and Dad’s reprimand. He asked: “Dad, what exactly was wrong with doing that thing with my knife, when I picked at my food?”

Dad simply said: “You just don’t. End of story.” And that was exactly that: end of story.

Then, the second memory is of… jumping on the bed! All kids have tried jumping on the bed at some time. We tried it too, but maybe our timing wasn’t so good: it was late at night and Mom and Dad were trying to sleep. Dad wasn’t impressed. Not even a bit. Let’s just say he put an end to it.

On a lighter note: Dad certainly had his funny side, his quirks, and his occasional eccentric behaviour that caused us some awkwardness. What stands out clearly was his dancing! Our dad seriously thought he was the very best dancer around. Sometimes, at a function or a party, when he was bringing out his dance moves, we couldn’t help but look at him and think to ourselves, “Dad! What are you doing?” Even now, the rest of the family still jump to his defence when we talk about his dancing, saying that his dance moves “fitted in well” for those times. (We’re not so sure, LOL)

We must say, however, that despite the cringe-worthiness to us of his dancing, it was always great to see him letting his hair down, and having fun.

***

As we look back on our upbringing there’s one thing we regret: Dad didn’t communicate much to us about his life, such as what it was like for him to grow up as a child in a rural village; about his schooling; about the early years of marriage to our mother. It’s something we know that he regretted too – that he didn’t share more of his stories. Maybe, had he done so, he’d have bonded in a lot of different ways with us, and we with him.

Don’t think from all that we’ve said that Dad didn’t show any affection to us when we were kids. He did. The thing is, really, that we seldom had occasions where we’d have a relaxed family conversation, like, for example, have him telling stories about when we were toddlers, or about things from his childhood.

Dad’s inability to connect with us in ways we wanted when we were youngsters was quite probably a result of the subtle pressure he and other men of his time faced to be that authority figure as head of the house. Perhaps there was an inner conflict of sorts that made it difficult for him to open up, and communicate more freely, in matters other than just those to do with our rugby. To us, it seemed like that.

Still on the topic of Dad not often talking things through with us: there is so much about our country’s apartheid history and how that affected us as a black family, yet he didn’t ever talk of that with us. Maybe he felt that we just wouldn’t understand certain things. Or, maybe he just wanted to protect us from any knowledge of the hurt that he and Mom experienced – and also our broader family and friends – during the apartheid era. He probably knew we were just too young to deal with learning of the kinds of trauma which he and our mom experienced as black South Africans.

Reflecting on his parenting of the time, we’ve come to realise that we should appreciate much more how he shielded us at that young age from the pain which discrimination and racism caused to our people. Looking back, there was no doubt what he was doing: protecting his children.

Only when we were about 19 or 20 did Dad slowly start to open up to us a bit about the things of life; about more than just how to tackle better on the rugby field, or kick a rugby ball further than the next guy. These days, that flawed communication that characterised Dad’s parenting would be an Achilles heel in a family situation. This is something we’re both working hard at as we move further into fatherhood: having good, open conversations with our children. But for Dad, back in the Eighties and the Nineties, it was usual for a father to be a rather closed book to his children.

Make no mistake, we both know that this is one thing Dad would have changed if he could have done it all again: He’d have tried to communicate better with us, and to have been more open. We admire him for having come to that realisation in his later years.

***

Looking at our rugby careers, his role was phenomenal.

The starting point has to be discipline. As we cast our minds back to the start of our careers in rugby, we see with new eyes the rock-solid foundation he laid for us: strict self-discipline. Through our father’s setting of very clear boundaries from when we were small, and his firm, fair disciplining of us, he taught us to really value discipline. He moulded us into disciplined young men.

That foundation helped us in a variety of ways, especially as we began to travel as professional players. Things like being punctual for practices; getting into the right mindset for a gym session; ignoring distractions and focusing on the task at hand. We’re grateful for how Dad instilled discipline in us, for it taught us to adapt, and to do what was required of us, something that is essential if one wants to succeed in top-level professional rugby.

Without our dad’s support and guidance as emerging rugby players, we certainly would not even have played for the first team at Hudson Park High School, never mind play at the high levels we did in later years.

Akona Ndungane of the Blue Bulls. Image: Dirk Kotze / Gallo Images

Before we get into the details of our dad’s support of our rugby over many years, we must get back to his name and its meaning: Zingisa – Persevere.

We can’t talk about our rugby careers and Dad’s influence without first dissecting this critical aspect of our father’s character. He modelled perseverance; he showed how to stick to something, no matter how challenging or even unpleasant it may be. Or how physically and emotionally draining. That’s what we watched, what we saw in action: Dad persevering.

There were numerous examples of this, the most obvious to those who knew him well, was in his work. He was a salesman, he covered thousands upon thousands of kilometres in his job to ensure that we as a family had all that we needed. For more than 20 years, twice a week, every week, he travelled the almost 200km stretch from Mthatha to East London for business, returning the same day. He’d often have to tackle the almost four-hour trip west, to Sterkspruit, and back again. We never heard him complain about his salesman’s lot in life, and all the travelling. He just got on with what he had to do.

At Dad’s funeral, a close friend and colleague spoke of the fact that our father never once called in sick. He spoke of what a man of integrity Dad was, and of how he took on wholeheartedly what he had to do. He described how, when the going got tough for our dad in his travels – like somewhere on the N2 late at night, after yet another business trip – our father would dig deep, and would persevere, as always.

With our father, it was the old story of actions speaking louder than words. During our rugby careers, when times got tough for us, his actions would influence ours – undoubtedly. Although he never said to us something like, “Sons, in life it’s really important that you keep your head down, stick at it, and persevere”, somehow we could do exactly that when the chips were down. The perseverance was ingrained in us; we’d seen him modelling it all our lives.

So, when injury hit during our careers, the gritting of teeth through the long rehab process almost came naturally. Looking back, that was thanks to Dad’s example.

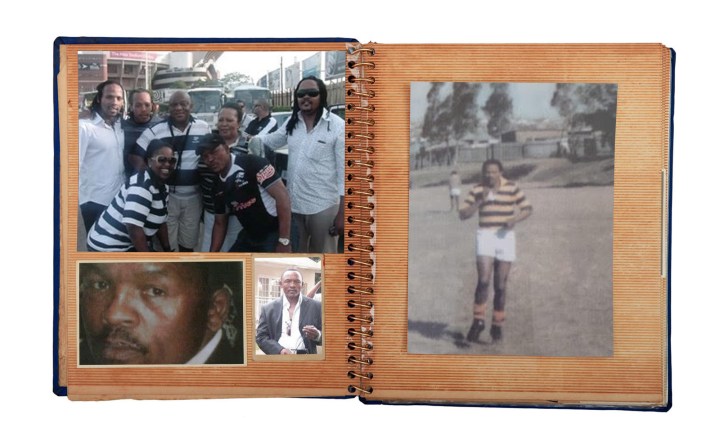

Rugby was in our blood. From very young it was rugby, rugby, rugby. Our earliest childhood memories are of rugby. Every Sunday, our routine was that, after church, we’d head back to our home in Gxulu for lunch; then, after lunch, we’d drive the 10km to the Rotary Stadium in Ngangelizwe, which is in Mthatha. There, we’d spend the afternoon watching Dad playing (later in his career, we watched him playing in the same team as our older brother, Mayidu). We loved those Sunday afternoons, with the whole community crowded around to support their team.

Dad played for a club called Wallabies. We, our brothers and ourselves all played for that club over the years. It has a rich history and was the club to belong to. He was a very good player. He was fast, with an impressive side-step; on that field, which in many places was uneven and unforgivingly hard, side-stepping, running with pace and tackling were not easy. Dad made it look simple, as though he was playing at Loftus or Newlands.

Our father could play anywhere in the backline, but his preferred positions were scrumhalf and wing. We’d watch him carefully as kids, soaking in what we saw; then later we’d imitate what we’d seen, reproducing the amazing tries of the day, many of which he’d played a key part in setting up, if not scoring them himself.

As we got into our teens, and Dad could see that we were serious about our rugby, he got involved in training us, especially in getting us really fit. He’d wake us up at 4am, saying: “Come on boys; time to go run.” Often, when we complained about getting up at such a crazy hour, he’d be quick to remind us that his Makhulu had frequently got him up at that exact same hour to run errands for her, like fetching the cows to plough the fields. The thing about that early-morning rugby training that stands out for us was that Dad wouldn’t just stand there watching us. He’d also run, even though he most often was way behind us, he was there with us. He could show what had to be done; it wasn’t just about saying what we had to do. That made a big difference to us, and to our motivation: Dad was with us.

Dad got us to see that hard work never stops, and that it pays off. When we were much younger, as young as 10 or 11, he’d wake us at 4am or 5am to plough the fields. We’d work hard, with him, and later in the season we’d see the fruit of our labour. And he made it abundantly clear, especially when the sun was beating down on us on those lands, that complaining wouldn’t help or change the situation. “Just get on with it,” he’d say.

It was exactly the same in our rugby training with Dad when we were older: Hard work was what was needed. As we moved ahead and into professional rugby much later, we were grateful to have been well taught by our father that there’s no substitute for hard work.

Odwa Ndungane of the Cell C Sharks crosses the line to score a try. Image: Michael Sheehan / Gallo Images

When we got to high school, having moved to stay with family in Amalinda in East London, Dad travelled all over to watch us, every Saturday. Remember, he did between 600km and 800km of business travel every week; then, already travel-fatigued, he’d head 200km back to watch us at Hudson Park, Cambridge, Selborne or Stirling High in East London, or would go to Dale College in King William’s Town (now Qonce) or to Queen’s College in Queenstown (Komani), or travel another two hours beyond East London to Kingswood College in Grahamstown (Makhanda) – to watch us play rugby. He never missed a match.

When one gets to under-19, under-20 and then under-21, you really don’t know how far your rugby is going to take you. It was our dad’s guidance, just his presence, that made the difference and which pushed us along into provincial and then franchise rugby. His support made all the difference. For us to know that he was there, on the side of the field, watching us every time we played, was amazing. There was just something about him that set us free to play our best. One often hears of boys and girls who are negatively affected by a parent’s presence on the touchline (most often by a father’s presence.) We were lucky; it wasn’t at all like that. Whether it was when we were playing for the Hudson Park under-14As, the Sharks or the Bulls, just knowing that Dad was there would make all the difference. We’d tackle harder. We’d chase after the ball faster, because Dad was there.

The post-match analysis was always fun. Dad was always so animated: “When the Number 8 came at you in the second half, that was a great side-step”; “Why did you kick when you were up against the touchline? You could have passed to that guy who was on your inside”; “That chip over the fullback’s head was brilliant” He was our number-one fan and supporter, no matter what the scoreboard said. He always had praise for us, and suggestions to help us to improve. Sometimes, during our careers, Dad would phone very soon after our game for his usual post-mortem, and often we’d not be able to talk right there and then. So we’d say: “Dad, I’ll call you back later.” But, there were many times when we’d forget to call back; we see now, that one can never know when “later” may be, or rather, whether there’ll even be a “later”. With Dad no longer with us, we realise that we must never take things for granted; we must make time for others.

***

Now that we’ve hung up our boots, we miss how he’d phone to give his two cents about our matches, and about rugby generally. To have him call to say: “Just calling to touch base and see how you’re doing.” There’s so much we miss about our father.

When you lose your father, there’s a strong sense of somebody huge no longer being there; someone who would have your back in difficult times. That feeling of him just being there, supporting, is what we miss.

Of course, now that we’re husbands and fathers, raising children of our own, we’d love him to meet our kids, and for them to spend time with him. It would be great to have him around and to be able to tap into the knowledge and wisdom he gained through his life experiences, and to say things like: “Dad, how do you think I should handle this?” Or: “What should I do about that?”

Although we never heard our father say, “Boys, I love you”, we know that he did love us. Through his actions, he showed us that he loved us. And through his actions, he taught us much that has equipped us well as we face life’s challenges, and as we grow as fathers. Most of all, he taught us discipline, the importance of family, and – perseverance. We’re grateful for that. We’re grateful to have had him as our dad. We miss him so much. DM/ML

Lessons from My Father is a series of interviews and stories collected and written by Steve Anderson. Anderson has been a high school teacher for 32 years, 26 of them at two schools in East London and the last six at a school in Cape Town where he heads up the Wellness and Development Department and teaches English and Life Orientation. Throughout his career he has had an interest in the part fathers play in the lives of their children. He says: “This series is not about holding up those who are featured as being ‘The Perfect Father’. It is simply a collection of stories, each told by a son or daughter whose life was, or whose life has been in some way positively impacted by their father… And it doesn’t take away the significant part played by mothering figures in the shaping of their children. Theirs are the stories of another series!

In case you missed it, also read My father’s daughter and the woman his family teachings ultimately shaped

My father’s daughter and the woman his family teachings ultimately shaped

A beautiful tribute to your father. He may not have said the words “I love you”, but his actions trumpeted his love for you.

“When you lose your father, there’s a strong sense of somebody huge no longer being there; someone who would have your back in difficult times.”. This resonated with me as something I have also felt with the loss of my father.