PROFILE

Nobel Laureate Annie Ernaux’s art of ‘autosociobiography’ – an appreciation

In this dispatch from Stockholm, Maureen Isaacson warms to the unique literary method of French author Annie Ernaux, who received this year’s Nobel Prize in Literature.

The Swedish Academy’s commitment, in recent years, to recognising genre-busting literature was reasserted when it awarded Annie Ernaux of France the Nobel Prize in Literature last month. Ernaux’s passionate, devastatingly painful tell-all memoir Getting Lost (originally published in French in 2001) now joins Svetlana Alexievich’s “documentary novels” and Bob Dylan’s lyrics in the canon of literary outsiders.

Ernaux (82) received the honour for “the courage and clinical acuity with which she uncovers the roots, estrangements and collective restraints of personal memory”. The classification of her work is a subject of its own, we’ve learnt: she has rejected the label autofiction, sees herself as an ethnographer, and aims for “something between literature, sociology and history”.

Getting Lost, the latest of her works to be published in English translation, is the journal that informed her previous novel, Simple Passion (1991). This journal, written between 1988 and 1990, records the passionate 48-year-old divorcee’s love affair with a married Russian diplomat, 13 years her junior. Ernaux decided to publish the journal so long after the novel as it is “a kind of oblation”. In the journal, she records daily thoughts and actions, “the things which constitute the novel of life that a love affair is (details from the socks he did not remove while making love to his desire to die at the wheel of a car)”.

As she writes in the introduction: facts have no place here; those can be checked in the archives. Instead, the journal is unrestrained in describing a desire so powerful that it drives her to the point of tears. This desire is reciprocal, although the man is “in every sense the shadow lover”, and even though he does not speak tender words “there is nothing but tenderness”. She is hooked on her own role as “iniatrix” – pleased with her transformation from inept lover into champion stud.

The affair, which began when the diplomat was tasked with accompanying a writing group on a junket to Moscow and Leningrad, and continued when they returned to France, boosts Ernaux’s fragile ego. (She has never been so beautiful, as everyone tells her.) This waiting, day and night, for S.’s telephone call becomes a subject on its own, so real as to be “a possession”. For her, “desire, writing and death have always been interchangeable”. Social distinction is of little consequence. Lunch with President François Mitterand, dinner with Prince Charles and Diana – neither of these can compare to her “desire for a man”, or the night in Leningrad she once spent with S. Even as she suffers in the uncertainty of her waiting, she knows this is the beauty of the arrangement, for they are “under the rule of passion”.

Betrayal is par for the course. Ernaux has no qualms about wanting to annihilate all obstacles, including S.’s wife, Maria. When she finally meets Maria, Ernaux is relieved that she is a bit stodgy but feels a sadness, which comes “with knowing, through unconscious memory, some of what she might be suffering… I ‘was’ her, in the old days, at parties where my husband showed interest in other women and G, his mistress, was present”. Ernaux is also saddened by the fact that she and S are “two-faced bastards”; and too because she must wait, until Thursday, to be alone with him.

Ernaux describes herself as a free woman, a whore, not the “good woman”, and she “can’t console anyone”. She is herself inconsolable as she waits for S. She fears ageing, flaccid thighs and a life confined to solitude.

After the academy’s announcement, we learnt that Ernaux supports the Yellow Vests protests in France, plus the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions campaign to end Israel’s oppression of Palestine. Yet at the stage of her life described in Getting Lost, her political consciousness is limited. She loves S. because he is a Soviet. “It’s the absolute mystery – exoticism, some might say. But why not? I am fascinated by the ‘Russian soul’, or the ‘Soviet soul’, or by the whole USSR, at once so physically close – culturally too (in the past) – and yet so different (I don’t have the same feeling about China or India, whose “otherness” is more radical – a racist sentiment?)”.

Ernaux’s first three novels are autobiographical. Cleaned Out (1973) details her sexual awakening and the trauma of her illegal abortion. Do What They Say or Else (1977) narrates a 15-year-old’s unsuccessful attempt to make sense of the world around her. The Frozen Woman (1981) takes up the transformative journey of a woman through marriage, motherhood and a domestic life as a wife that “freezes” her.

Having written the novels, she dropped what she called the protective mask of fiction, as she explained in her 1993 essay, “The Transpersonal I”. A Man’s Place (1983) was the first of three memoirs, or “autosociobiographical texts”, which focused on the intimate details of Ernaux’s family life; she aimed for “a family ethnography”, which included dissection of their collective class journey. (She worked as a secondary school teacher and for Cned, the Centre for Distance Education; she is currently a professor of literature, which counts as a significant elevation above her early life and career.) Her precise and careful yet unsparing portrait of her father and his milieu is among the best of its kind. While detailing his transformation from factory worker to small-town café and grocery store owner, Ernaux writes of her repulsion by his mannerisms such as his wiping his knife on his trousers after eating.

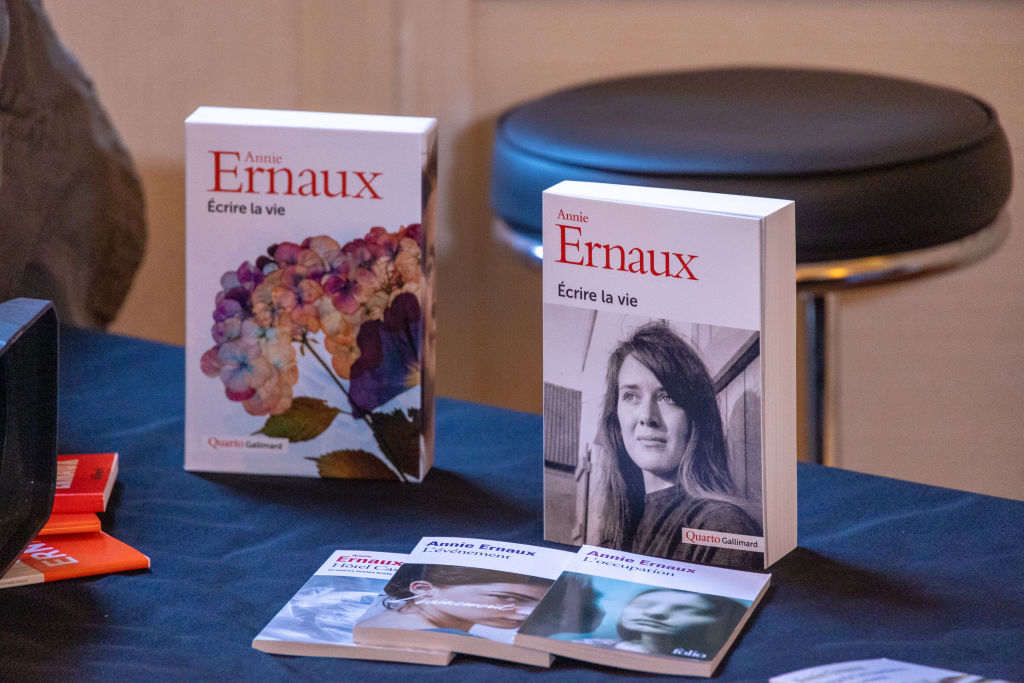

French author Annie Ernaux gives a press conference after winning the Nobel Prize in Literature on 6 October 2022 in Paris, France. Image: Marc Piasecki / Getty Images

A close-up of French author Annie Ernaux’s book during a press conference after winning Nobel Prize in Literature on 6 October 2022 in Paris, France. Image: Marc Piasecki / Getty Images

Ernaux paints a compelling portrait of her mother, meanwhile, in A Woman’s Story (1987). It was this book that she applied the description, “something between literature, sociology and history”, to. Ernaux’s mother, also a former factory worker, who worked alongside her husband in the café and store and proudly sent her only daughter to a Catholic convent. The accumulation of facts about Ernaux’s mother’s life, her unrealised desires and aspirations, her peculiarities and her kindnesses, and her descent into the fog and anxiety of Alzheimer’s two years before her death, is exquisitely rendered.

Ernaux’s mother was an avid reader who was eager to keep up with her daughter’s metamorphosis. She believed that the rich were “just like us”, while Ernaux’s father remained mired in the inferiority and shame of his origins. That his daughter chose to abandon the patois of her home drove him to rage. In fact, there was certainly no shortage of rage in their household. When Ernaux was not yet 12, her father tried to kill her mother after she, in a very bad mood, fired off a fusillade of criticism at him. Ernaux elucidated this incident, how it blew over, and its lingering effect on her in Shame (1997).

She has written more than 20 books in all. Her multi-award winning The Years (2008) is perhaps the most prominent among English readers. The book combines a social history of France with a personal history spanning the six-plus decades from the year of her birth in 1940 to 2006. In The Years Ernaux abandons the personal pronoun. She writes: “There is no ‘I’ in what she views as a sort of impersonal autobiography. There is only ‘one’ and ‘we’, as if now it were her turn to tell the story of the time-before.’” Ernaux is writing against time, what she calls a slippery narrative, because she understands that all images of her past will soon disappear. The Years thus comprises what she calls “abbreviated memories”; her aim is to retrieve “the memory of collective memory in an individual memory” that will capture “the lived dimension of History”.

This monumental undertaking is what the Nobel committee referred to in its citation.

The Years is a huge and ambitious project that undoubtedly breaks with tradition; the writing is always easy, short and sharp; but for my money, the control and focus of the beautiful “autosociobiographical” texts about her father and her mother are unsurpassable. To know Ernaux, the 17th woman to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature, out of 119 awardees in total, it’s ironically best to begin with A Man’s Place. DM/ML

Maureen Isaacson is an independent South African journalist based in Stockholm.

Comments - Please login in order to comment.