ANOTHER SORT OF LEARNING

The Unicorn School in the back-country outside Colesberg, Northern Cape

The crippling cycle of rural South African poverty is broken on a farm deep in the Karoo. But somewhere along the Colesberg-Oorlogspoort road, there is a spot that is magical at first light.

The deep, wrap-around silence is broken by the first joyous song of a Karoo chat. Then the bleat of a lamb. Then the whisper of wind through grass. Then the lisping creak of a spinning windpump.

On any given school day, there is another sound, a faint growl that grows steadily louder. It is a convoy of white vehicles winding along a gravel road through the veld, trailing a veil of dust. The kids are off to school.

Set among blonde grasses, flat-topped hills, spinning wind pumps and exclamation-mark poplars, the neat red roofs and white walls are visible from kilometres away. The South African flag flutters above a quadrangle of clipped green grass.

An education phenomenon

This farm school is part of the Hantam Community Education Trust (HCET). At any one time, you will find about 200 children here, mostly the sons and daughters of Karoo farmworkers, including nomadic sheep-shearer clans who live in a nearby shanty settlement called Die Nek — The Neck. They are among South Africa’s poorest people, facing the attendant problems of malnutrition, ill health, alcohol abuse, isolation, ignorance and broken families.

The very real success stories coming out of this school are those of children from unpromising backgrounds who have gone on to become nurses, doctors, electricians, teachers, occupational therapists, accountants, plumbers, bank-tellers, welders, trackers, chefs and businessmen.

In South Africa, the youth unemployment rate (first quarter 2022 estimate) is 64%, for those aged 15 to 24 years old. In rural areas like this one, it is usually even higher. Yet more than 90% of the graduates from Umthombo Wolwazi Farm School, operating since 1992, are employed in stable jobs.

“In one generation, we have made visible progress in breaking the downward spiral of poverty,” says Lesley Osler, one of the founders of the school, along with Clare Barnes-Webb and Anja Pienaar.

But it was certainly not the plan in 1989.

Back then, Barnes-Webb was running a farm shop on land her husband Peter managed, selling basic foods to farmworkers at cost price every Friday. The adults brought along their children, and many were clearly malnourished, she recalls. She remembers seeing that injuries were often treated with random remedies: boot polish, toothpaste or oil.

A convoy crosses the vlaktes near Colesberg, carrying children to an exceptional farm school. Image: Chris Marais

A donkey cart vignette at Die Nek settlement. Image: Chris Marais

The HCET campus in the background is working to uplift the poorest of the Karoo’s poor. Image: Chris Marais

Barnes-Webb cleaned and brightened a farmstead storeroom, made play-dough, and rounded up toys, crayons and paper. She collaborated with neighbours Lesley Osler (a former teacher) and Anja Pienaar (a former financial controller), who were both keen to bring children from their farms to the playschool.

Then came a chance connection with Jane Evans, an early childhood development expert who had started a training centre for rural women from Viljoenskroon in the Free State. Evans advised that the local parents identify three women who could be sent to her project to be trained as early childhood development teachers. A meeting was organised and local farmers brought in 450 farmworkers, said Lesley Osler.

A school is born

By the end of the meeting, the community had chosen three young women: Lettie Martins, Nombulelo Matyeke and Thembakazi Matyeke. The trio took the train to Viljoenskroon and came back two weeks later, bubbling over with ideas and enthusiasm. The little playschool brought the new teachers together with the children three times a week, and they all flourished.

But there were no plans to take things further. It was the parents of the children who pushed for something more.

“A number of the parents approached us, and told us their hearts were heavy,” says Osler. “We were shocked. What could be wrong? We knew the children were thriving. It turns out the parents now had grave misgivings about their children’s options the next year. The nearest farm school was a 15 kilometre walk away, and it was a bleak and dreary place with two undertrained teachers.

Lesley and Maeder Osler, plus hounds, at Hanglip Farm. Image: Chris Marais

“So we asked the parents what they had in mind and they said: a primary school. I had been a teacher, but not one of us knew anything about actually running a school. Well, we tossed some ideas around, then called a meeting with the whole community, farmers and everyone. We wanted to know who would back such an initiative.”

The road to Umthombo Wolwazi Farm School. Image: Chris Marais

During breaks and after school, there is usually a sprawling soccer game on the go. Image: Chris Marais

Netball is a perfect game for a small school courtyard. Image: Chris Marais

Play is the best form of education in early childhood. Image: Chris Marais

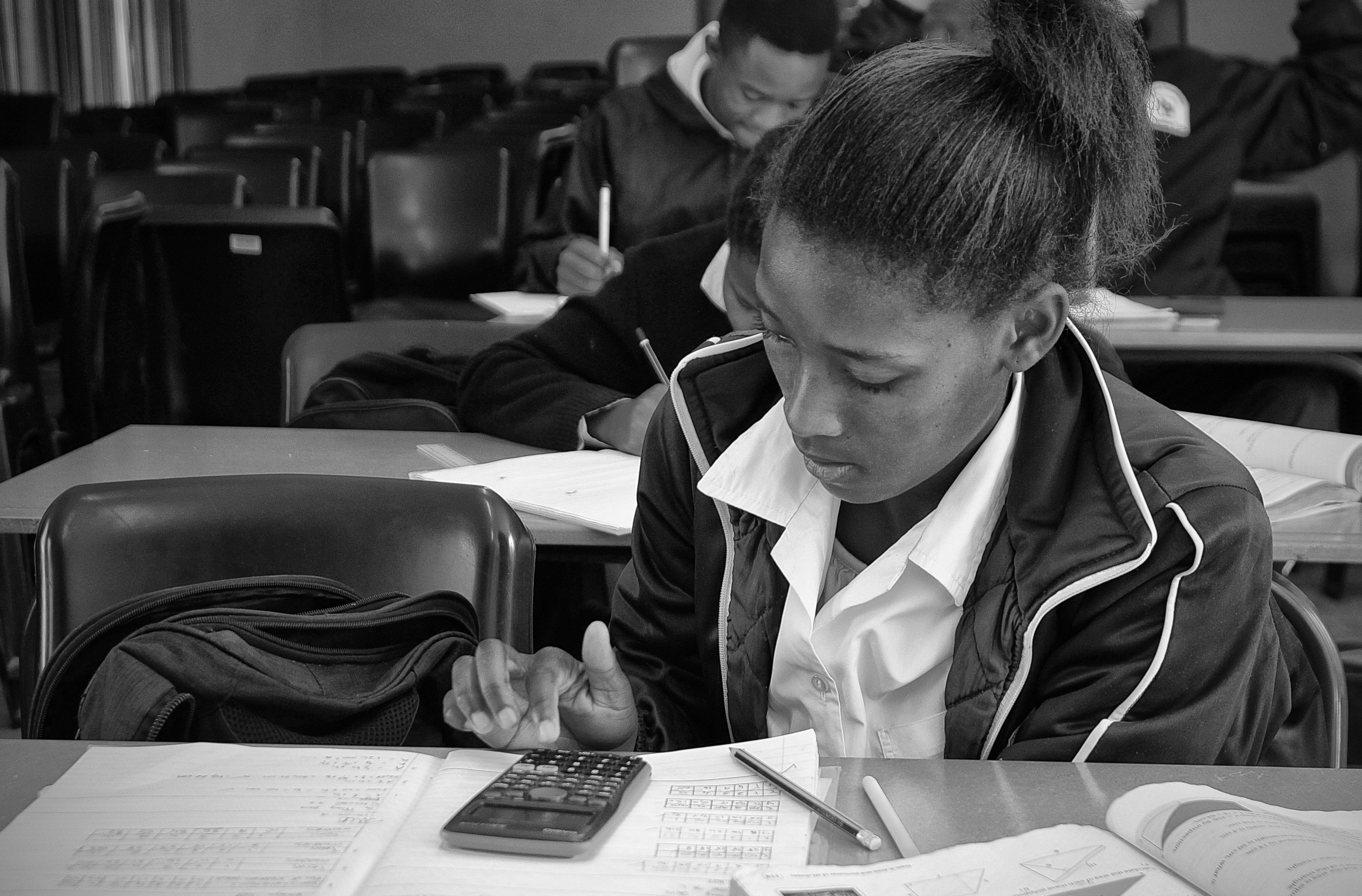

The school takes children from Pre-grade right up to Grade 9, and offers bursary for further studies. Image: Chris Marais

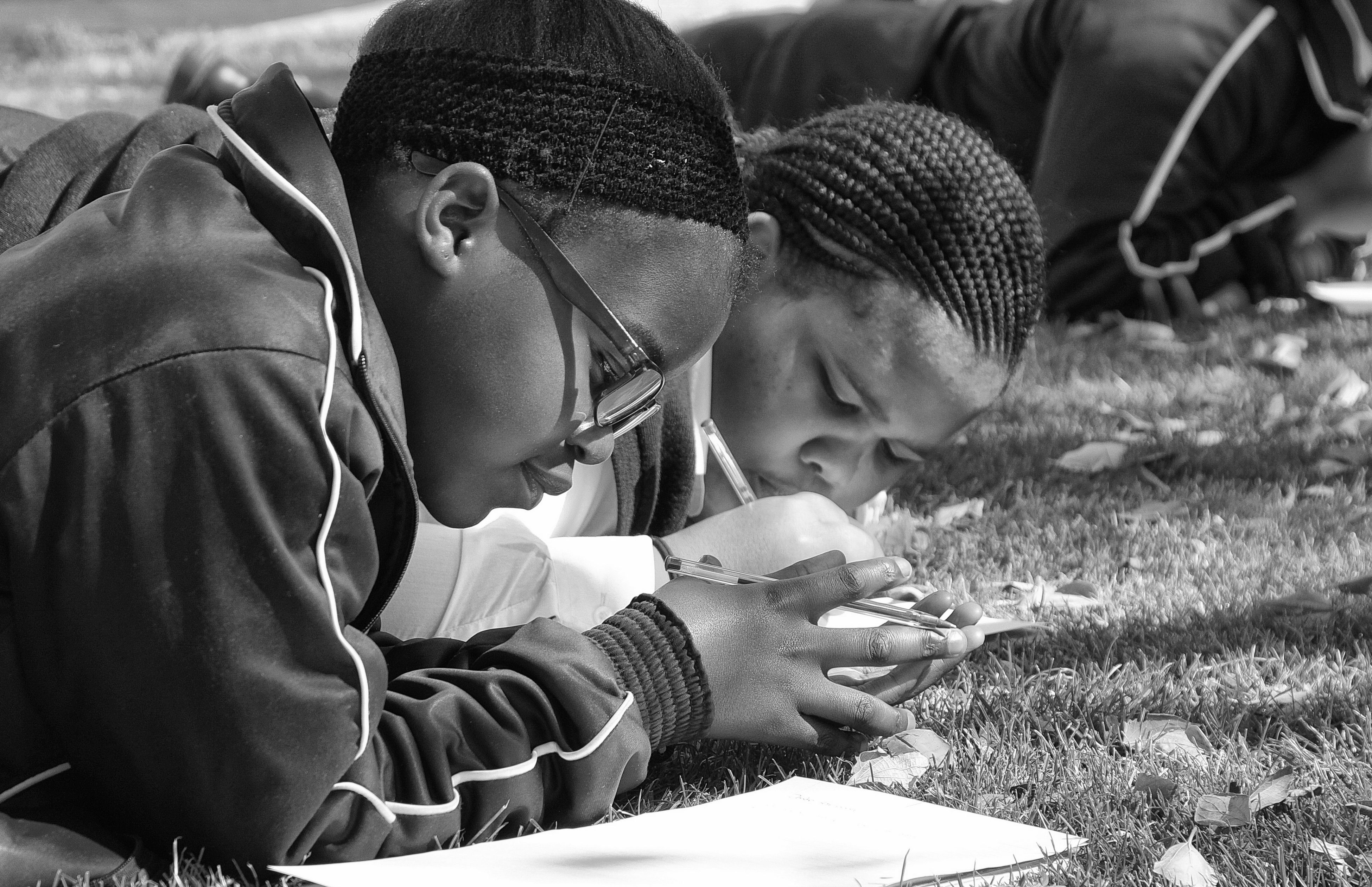

On the grass, in the quad, writing poetry. Image: Chris Marais

Hanna Phemba and the Persona doll the children named Thabo. Image: Chris Marais

The three founders of the Hantam Community Education Trust. From left: Anja Pienaar, Clare Barnes-Webb and Lesley Osler. Image: Chris Marais

A fountain of knowledge

It turned out that there was support from various quarters. With some sweat equity from parents, donations of space, furniture and goods from farmers, plus the gift of electricity from Eskom, Osler, Pienaar and Barnes-Webb transformed some old buildings into a school at Grootfontein farm. They planned to take it up to Standard Four (Grade Six).

“We wanted it to be the best we could make it,” said Barnes-Webb. “It had to be good enough for our own children.”

In 1992, the new school was named Umthombo Wolwazi (Fountain of Knowledge) and started off with 60 children. The Department of Basic Education contributed by paying some of the teachers’ salaries.

By the next year, they had 96 children coming from 28 farms in a 50km radius.

When the school needed to expand again, Osler, Pienaar and Barnes-Webb had to form a Trust in order to raise more funds. They approached embassies, foundations and corporates, occasionally travelling to Paris, London and New York for the funding that would give their learners the best possible chance in life.

Lesley Osler: “We teach people that they have every right to be treated with dignity and respect. There’s a ripple effect on us, the staff and the community. I’ll walk a thousand miles for them, and they for us.”

Lesley Osler checking up on a sick child at Die Nek. Image: Chris Marais

Skilled and gainfully employed

For those who cannot cope with academic life, who dropped out due to circumstances like pregnancy, disability or other issues, the Trust runs Youth Empowerment Programmes. This is Estelle Jacobs’ baby.

Since 2008, she has been the facilitator, fixer, and general force of nature behind the Trust’s secret weapon for creating employable graduates: the Hantam Hospitality School.

This rather remarkable institute is housed in a side street of Colesberg and uses donated funding to train disadvantaged youngsters in useful skills like basic and advanced cooking, housekeeping, front of house and basic computer skills over six months. Every graduate then does an internship with lodges, guesthouses and restaurants in the district.

Every year there is a new intake of a dozen or so new pupils sourced by word of mouth from a wide catchment area. Many come from the Colesberg district, but also Gariep, Noupoort, De Aar, Nieu-Bethesda, Trompsburg, Bethulie, Cradock, Tarkastad, Steynsburg and beyond.

The resulting employment rate for the hundreds of graduates from this school over the years is around 96%, most of them in steady jobs. You will find them working in supermarkets, the kitchens of old age homes, in fast food establishments, in restaurants and guesthouses all over the Karoo.

Mothers and babies in the Effective Parenting Programme. Image: Chris Marais

A mother and child at Die Nek, a settlement of former Karretjiemense (nomadic shearers). Many of their children attend Umthombo Wolwazi. Image: Chris Marais

Lettie Martin has made a positive difference in the lives of hundreds of children. Image: Chris Marais

New Hantam Hospitality School students learn about measuring instruments for baking. Image: Chris Marais

At the Handyman School, youngsters learn how to weld, tile, solder, roof, paint, plaster and do basic plumbing. Image: Chris Marais

There is a community clinic, including a pharmacy, across the road from the school. It is also part of the Trust. Image: Chris Marais

Hardware and soft skills

At the back of the Hospitality house, five young men are wielding power tools under the close supervision of Estelle Jacobs’s brother, Jan. This is the new Hantam Handyman School, and these youngsters are fine-tuning their skills before graduating.

One has a slight disability and the others just did not progress well in school. But their pride in what they can do is tangible. The results of their work are around them. They started in January 2021 by fitting a ceiling in an old outbuilding, painting it, installing lights before moving on to a bathroom in one of the teachers’ houses, fixing broken chairs, repairing stoves and making cages for gas bottles. They have learnt to weld security gates and burglar bars, and can build dog kennels out of pallets.

“Over six months I teach them roofing, basic building, tiling, plumbing, welding, painting, a bit of electrical work and carpentry. But just as important are the softer skills,” says Jan Jacobs.

“I try to build them up, teach them to be punctual, polite and reliable, how to work out a quote, how to accurately cost out materials and labour, how to manage their time, and how to work logically and neatly. By the end of this course, just like the Hospitality students, they will be placed as interns at lodges or B+Bs, and be paid a small salary.

“I also teach them how to spot an opportunity, and how to make themselves useful or even indispensable.”

They don’t just graduate with skills, says Estelle. Each one also gets a toolkit that contains an angle grinder, a gas soldering kit, some basic painting materials, pliers, plumbing tools, a trowel and a saw.”

This is just the beginning, though. They are mentored and supported through the first three years of their working careers. “We are in constant contact with them via WhatsApp. That’s why they have such a high retention rate.”

The HCET also runs a Farm Workers’ Apprenticeship Programme where young people can be trained and mentored before becoming agricultural interns. These graduates are in high demand on local farms.

Back at Umthombo Wolwazi, the three founders, now approaching their eighties, have handed over the reins to Jacobs and Mary Ann Smith, who used to manage Gary Player’s horse farm up the road.

At the entrance to the admin wing, one simple sign tells the whole story of the Hantam Trust project. It says: “Never, never, never give up.” DM/ ML

‘Karoo Roads III’ book cover. Image: Supplied

This is an extract from Karoo Roads III – The Adventure Continues, by Chris Marais and Julienne du Toit. For author-signed, first-edition copies of Karoo Roads III or the complete collection of Karoo Roads books, email Julienne du Toit at [email protected]

In case you missed it, also read The Rescuers: In the Karoo with modern-day South African heroes

The Rescuers: In the Karoo with modern-day South African heroes

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

What an incredible and inspiring story!

This is proof that local action will bring meaningful change to communities ! Take action get involved to retain your own sanity & benefit

You strike a woman, you strike a rock—Bravo to you all. What a joy to read the excellent news sandwiched between an epic day of bad news.

This is very important story that deserves a high profile. As a Karoo ex farm girl myself, it us gratifying but it has more universal ring to it; about respect. I sincerely hope that Johan Rupert, who own large tracts of land around Cradock and Graaff-Reinet, has made significant donations to this project. Similarities to the Goedgedacht school philosophy and programmes from their base in Riebeek Kasteel region, Western Cape.

Thank you for this inspiring feel-good story abour these wonderful initiatives in the Karoo. Amidst all the doom and gloom of South Africa’s current woes, it is so good to be reminded of the positive upbuilding actions taken by so many ordinary Sourh Africans to improve the lives of those around them. Viva ubuntu viva!

What an inspiring story!!! Commitment and generosity of spirit from a few enlightened individuals creating so much hope, progress and prosperity within one community.

This is the new South Africa we all dreamt of. Inspiring story Julienne and Chris – we’re loving your books. And we’ll done to those Karoo farming communities for showing the rest of us what can be done!