SCOFF

In search of an Epicurean Emoji-nation

South African culinary communication requires regionally specific emojis.

How the mighty have fallen. I used to pride myself on never, ever using emojis. I regarded them as infantilising, toddler-esque signifiers of emotional reduction. The lowest form of lazy. So much so that I got hysterical if my child fiddled with my phone for fear that he might inadvertently press send to someone who would then think that I was dispatching rows of inane smiley faces.

And then came Covid. Almost all of what were once IRL (in real life) exchanges pivoted online. Staccato WhatsApp messages were in danger of destroying long nurtured relationships. The hitherto despised digital pictograms were pressed into service to ensure an understanding of intent that was previously brought about through voice tone, facial expression and gesture.

I blame Daily Maverick and Hannerie Visser of Studio H for turning what I initially understood as a pandemic induced, short term, necessary evil into an all-consuming addiction. In mid-2020, I wrote a story for TGIFood about indigenous millet and why this heritage grain was only available in the bird food section of supermarkets. While researching the article I made all sorts of millet based tasty treats. Including beer. When I sent a photo of my bubbling brew to the super stylish Ms Visser she replied with the following compound signage:

Beer plus budgie (below) = millet beer. (Images: Google Bier Emoji & emoji® brand Icons)

I was charmed, disarmed, and inspired. Exponential emojifying of absolutely everything ensued. In the post pandemic period, the cocooning misanthrope in me has not really returned to in person social service. I am much more online than I once was, and my emoji obsession seemingly knows no bounds. Which is why I am increasingly pained by the lack of South African specific images. I need more than our nation’s flag. I want a set of symbols that allow me to articulate regional activities and archetypes.

The debate around emoji representation is not new. As early as 2015, Amy Butcher’s New York Times essay argued that, “These tiny, insignificant images begin to create an everyday narrative, and it’s deeply problematic that one might consistently find their identity or demographic lacking, or pigeonholed, or altogether absent.” Since then, emojis have become much more inclusive. Images of women as professionals – not just brides, flamenco dancers and polished nails – have appeared. There are now gender-neutral symbols, waving hands in all skin tones, and icons that represent different types of disability. But vast areas of life remain unrepresented.

Japanese Kare-raisu curry doubling up as Mogodu Monday. (Image: emoji.co.uk)

Since almost all my communication is culinary, what I really want is our own epicurean emojis. While Eurocentric and Asian ingredients, recipes and cooking/eating equipment are well represented, I find that I am unable to adequately express myself with the symbols set out on my mobile. My desire for calabash, kota and teeny tiny jaffle iron icons is obviously emotional, but it is also economic. In a world where people increasingly communicate via emoji, such symbols translate into sales. In the immediate aftermath of the introduction of a dumpling emoji, San Francisco restaurants serving such stuff reported that their revenue tripled.

My struggle to describe homegrown edibles in emojis has led me to repurpose pre-existing international emojis. The symbol designated as a South American arepa flat bread (a greyish circle with griddle marks on it) makes a perfectly good roosterkoek. The emoji intended to be Japanese Kare-raisu curry can double up as Mogodu Monday. What I presume is supposed to be short-grained rice is a decent visual stand-in for samp.

There are various jam emojis that can be used to communicate the Afrikaans expression “Om gekonfyt te wees” – literally know your jam but metaphorically to be good at something. At a push one could use a combination of the pre-existing plum and worm emojis to convey the Zulu proverb “Ikhiwane elihle ligcwala izibungu” – a beautiful looking fig is full of worms – to warn the gullible not to be too trusting.

But borrowed emojis can only take us so far. Yellow, American style corn on the cob is not interchangeable with green mielies or heritage Rainbow Maize. The hot dog symbol isn’t a substitute for a coil of boerewors. Braai, bunny chow, dombolo, koeksister, magwinya… the edible omissions are endless.

South Africans have so much untapped proverbial potential. I am sure that a clever graphic designer could come up with a recognisable symbol to allow me to represent the sense of “Sho, uyiskhokho!” (Literally the hard crust of dried maize meal porridge at the bottom of a pot but actually a Tsotsitaal expression denoting admiration for a street-smart individual’s traits of a tough, resilient stubbornness). The Zulu phrase “kwafa gula linamasi” (direct translation: the calabash full of amasi broke; metaphorical meaning: all hope is lost) is crying out for an emoji.

Fortunately, our calabash is not broken and there is still hope. In theory, anyone can propose an addition to the emoji library. For a new image to make it onto our screens, applications (with details as to expected usage, cultural importance, and metaphorical meanings) must be made to the Silicon Valley based Unicode Consortium. If approved, the new emoji is then standardised across all digital devices such that the image sent on an Apple iPhone arrives looking the same on a Samsung. This year 31 new emojis (the only food images being a pea pod and a ginger root) were approved to be released alongside Unicode 15.0 onto all major platforms by late 2022 or early 2023.

The bad news is that the Unicode board is made up almost entirely of large tech company representatives: Microsoft, Adobe, Apple, Google, Facebook, Salesforce and Netflix. Campaign group Emojination (which pushes for greater representation among the official set of emojis) argues that the Unicode panel is “skewed male, white, and engineers. They specialise in encoding. Such a review process certainly is less than ideal for promoting a vibrant visual language used throughout the world”. The good news is that Emojination activists recently crowdfunded the entry fee required to get a representative on the panel.

If we want our edible icons represented, we will have to put in the effort to fight for them. Latin America leads the way in its understanding of food as intangible culture with tangible economic implications. In addition to the obvious buy and sell financial gains of being able to click on an emoji when ordering takeaway meals there are also more abstract image upgrades relating to the replacement of negative stereotypes associated with previously disadvantaged food genres with more modern, desirable depictions.

The aforementioned Venezuelan arepa that I am using as a stand-in for roosterkoek is a prime example of a regional food culture petitioning and ultimately, in 2020, achieving approval for an iconic national eating experience.

Venezuelan Pride, an arepa emoji has been introduced. (Image: ululeo.com)

Food and identity are intertwined. Arepa emoji designer Sebastian Delmont agrees that “Some even put food emojis in their social media display name as a way to signal their cultural origins, much like a flag is used”. Chasen Le Hara, the designer of the tamale emoji (also approved in 2020) says that “Emojis help represent our culture in the social media space. When our people find the tamale symbol, I hope that they think it’s a win for us Mexicans and that our culture is better represented because we have one of our popular dishes as an emoji.”

Botlhale Baily, chef-patron of Alexandra township’s ultimate kota hot spot for cool people, observes that, “What they did with the arepa and the tamale is inspiring. Imagine what we could do if we had a kota emoji. The majority of our customers are acquired through our online presence, and they tend to take the visuals they see and share them. For those who don’t already know, adding an emoji would bring awareness but for our customers who have already bought into the culture and understand the significance of the food, adding an emoji would bring about an excitement that they are part of something that is accepted and seen on a global stage.”

A google search suggests that there was once a ZA Emoji app that had a few food images (koeksister, chop, the word “lekker” and an Nguni cow) as stickers rather than actual emojis but clicking on the link results in a message that the domain is unavailable. Ivorian digital artist O’Plérou Grebet (@zouzoukwa) has created predominantly West African food stickers and a free app where they can be downloaded.

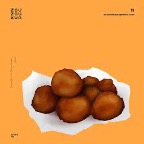

There are pictures of edibles and quaffables such as foufou, cassava flour, plantains and bissap rouge hibiscus tea. Grebet’s only explicitly southern African image is a potjie pot (charmingly described as “petite marmite à trois pieds servant à faire le potjiekos, ragoût Sud Africain”). Those seeking to add another Mzansi applicable emoji can also use the gbofloto (fried dough balls) sticker as a form of vetkoek/magwinya.

Ivorian digital artist O’Plérou Grebet’s gbofloto make beautiful vetkoek (credit: @zouzoukwa_ , Zouzoukwa)

As with the ZA Emoji app, these delightful designs aren’t actual emojis. They haven’t been approved by the Unicode Consortium and they can only be used as stand-alone stickers. Which means I can’t put the faux vetkoek into a WhatsApp sentence.

There are areas where South Africans could join forces with other international interest groups. In Zulu the word for courage and the word for liver are both isibindi because bravery is symbolically associated with this organ. So, we need a liver emoji. As does Dr Shuhan He from Massachusetts General Hospital, lead author of a December 2021 paper in Hepatology (published by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases) entitled Why We Need a Liver Emoji. Dr He points out that there are many, many alcoholic drink emojis but no liver. In January 2022, Dr He submitted 10 medical emojis (including a liver) to the Unicode Consortium for consideration. I don’t see any of them among the latest list…

Emojis are an increasingly important communication tool worldwide so it is important that we shouldn’t be stifled in what we want to say. Even if what we want to say makes us cross. Which it almost certainly will. In 2016, campaigners in Valencia petitioned for a Paella emoji to be introduced but then objected to the image because: “To the dismay of the authors of the original paella emoji proposal, the mixed ingredients used… did not match those used in traditional recipes from Valencia”, says Emojipedia’s editor Jeremy Burge.

If we ever achieve an Mzansi specific selection, I predict bitter battles over the direction of twist in the koeksister emoji… DM/TGIFood

The author supports the Saartjie Baartman Centre for Women and Children in Manenberg. Saartjie Baartman Centre

Comments - Please login in order to comment.