SCOFF

Cooking in lockdown isn’t entirely for the birds

If we are what we eat then I am ancient and cheap. Many of those lucky enough to have been comfortable but bored (rather than destitute and hungry) during the Covid-19 lockdown have sought out projects to pass the time. Mine has been cooking with budgie seed.

Introducing Anna Trapido’s new monthly column in TGIFood, SCOFF.

It is not as daft as it sounds. I don’t own a bird but I am interested in ancient grains. For years I have walked down the pet food aisle in supermarkets and been peripherally aware that the packets labelled ‘budgie food’ contained mostly millet. Millet is a collective name for a large group of small-grained, bead-like, gluten-free cereals. Some, such as Finger millet and Pearl millet are indigenous to Sub-Saharan Africa while others (including Foxtail, Kodo and Proso millets) originated in Asia.

The day before lockdown I was stocking up on dog food for my actual dog and, on a whim, I took a closer look at the budgie food. The packet listed “manna, millet, oats” as contents so I bought a 1-kilogram bag for R38. There is no millet for sale in the people section of my supermarket but a well-known online health food company sells imported, Foxtail millet grains at R85 for 1kg. In fairness, the products are not exactly equivalent but, even so, the bird seed seemed like a good deal.

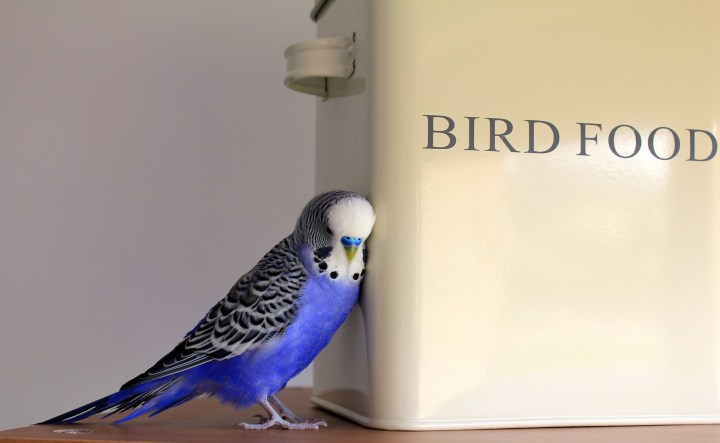

Seriously. (In case you thought we were kidding.) (Photo: Anna Trapido)

My plan was to cook and consume the contents myself. There was nothing on the packet that explicitly said it was or was not fit for human consumption so before I started to cook I called the bird seed company’s customer care line and made enquiries. I was told that it was “dust, mold, insect, pesticide and GMO-free” and was then referred on to Leon Scheepers, marketing manager at Pride Milling Co, who seemed amused/ bemused but assured me that, as a non-budgie, I could safely eat budgie seed if I wanted to.

Sprouting millet (and a few oats). (Photo: Anna Trapido)

On closer inspection I could see that my bag of budgie food was made up of local millet forms. It was approximately two thirds finger millet (Eleusine coracana) and a third pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum). There were also a few oats scattered in. Both Finger millet (Finger millet) and Pearl Millet (Pearl millet) are believed to have been domesticated over 5,000 years ago in Africa (Andrews and Kumar, 1992) and are widely cultivated across the continent from the Sahelian (Sahara Desert margin) countries down to South Africa. Pearl millet distribution tends to be more westerly and Finger millet is mostly grown along the eastern side of the continent Both are also grown in India where they were introduced approximately 3,000 years ago. Both Finger millet and Pearl millet are high in fibre, phytochemicals, minerals and vitamins. Pearl millet also has one of the best essential amino acid compositions of all the cereals. Both are gluten free. Both can be cultivated in areas with low rainfall, high temperatures and shallow, sandy soils.

Millet (and a few oats) unprocessed (straight from budgie food bag). (Photo: Anna Trapido)

In South Africa Finger millet is variously known as mvohoho (Tshivenda), uphoko (isiZulu), osgras (Afrikaans), mpogo (Sepedi) and majolothi (isiNdebele). Pearl millet is referred to as manna (Afrikaans), leotsa (Sepedi), inyouti (isiNdebele), luvhele (Tshivenda) and unyawothi (isiZulu). Both forms are traditionally ground into flour for porridges and/or fermented. While both Pearl millet and Finger millet are still grown and consumed in rural Limpopo, neither is available in urban supermarkets or health stores. Both can occasionally be purchased at taxi ranks and other commuter hubs in Pretoria and Polokwane.

Millet made into ‘dhal’-like mélange. (Photo: Anna Trapido)

My first experiments involved cooking the millet seeds whole. Birds use a rolling beak motion to crack open the tiny shell to get to the millet inside. Since I have no beak, I worried that, eaten whole, the millet might be too tough for my teeth. To get around this problem I soaked it overnight then drained and steamed it to partially gelatinise and soften the starch. I also dry roasted the seeds until they began to pop. I then cooked the millet as if I were making lentil dhal with cumin, cardamom, coriander, turmeric, ginger, garlic, chili and a slosh of chicken stock. I don’t own a pressure cooker and the cooking time was considerably longer than I had expected but the flavours were ultimately worth the roughly two hours the seeds took to soften. The result was a rich, almost-nutty, aromatic and comfortingly creamy, mélange. The next night I made the same recipe again but I replaced half of the stock with coconut milk. The night after that I folded the couple of leftover tablespoons into a bowl of (durum wheat) couscous which added great depth of taste and texture.

I also ground my bird seed into a fine, powdery flour using my handheld blender. A word to the wise – grinding must be done in a deep vessel or the millet will spray everywhere. I modified a flapjack/griddle cake recipe replacing wheat with millet flour. The results were fluffy textured and delicious. Infinitely superior to the same recipe made with either wheat or sorghum flour. For my second batch I used amasi rather than milk in the batter which gave a richer flavour and an even more bouffant texture. Both were lovely with a drizzle of honey. The lack of gluten made my attempts at millet muffins denser than wheat flour muffins but very pleasant nonetheless.

By this stage my family were tiring of bird seed but I pressed on regardless and made two very pleasant ground millet flour porridges. My first bowl followed a Venda-style mukapu recipe into which I folded a tablespoon of peanut butter to accentuate the rich, nutty taste. My second, a modified European-style breakfast porridge made with milk and butter was wonderful with honey and a dollop of full cream yoghurt.

The lockdown alcohol prohibition led to the brewing of budgie beer. I soaked then sprouted my millet under a damp cloth. Once the seeds had put out spindly shoots I dried and then ground them into a coarse textured flour. I made a thick gruel which I then cooled and fermented à la umqombothi. After three days I had a drink that tasted like a mildly alcoholic, double-thick malted milkshake with a fruity aroma and a yeasty, tangy finish.

All the above is evidence of a person with far too much time on her hands but there is also a more serious side to my bird seed project. Anyone evaluating the status accorded to indigenous ingredients in South Africa need look no further than the marketing of local millets. While international ancient grains such as quinoa take pride of place on our delicatessen and supermarket shelves and the Asian millets are sometimes stocked in health food stores, delicious, versatile, health promoting, climate resilient local heritage millets are almost exclusively sold as bird food.

In 1878 Zulu King Cetshwayo KaMpande (who famously led the Zulu nation to 1879 victory against the British in the Battle of Isandlwana) sent a message and a bag full of Finger millet to Natal’s Secretary for Native Affairs Theophilus Shepstone. The King’s message ran “If you can count the number of uphoko grains in this sack then you may also be able to count the number of my warriors.”

Millet seed ground into flour. (Photo: Anna Trapido)

In the last 142 years millets have made the ignominious transition from battlefield to bird cage as monotonously unhealthy, maize-heavy eating patterns have displaced heritage cereals. Under ideal conditions, maize can be more productive and less labour intensive to grow and process than millets but very little of South Africa’s land fits that description. The long-term social, medical, economic and ecological consequences of excessive maize cultivation and consumption are far from ideal. Africa’s heritage millets have a noble history and a valuable role to play in the conservation of culinary culture, biodiversity, health, food sovereignty and security. Plus, they taste great. I haven’t yet noticed the “superb feathering and enhanced colouring” that the budgie food bag promised but I have felt extremely well throughout my epicurean experiment. Only the truly bird brained would fail to recognise that our millets are marvelous.

Millet Flour Flapjacks

Millet flour flapjacks. (Photo: Anna Trapido)

120g milk

2 eggs

25g butter (melted)

170g millet flour

30g sugar

8g baking powder

Method

In bowl 1 combine milk and eggs.

In bowl 2 combine millet flour, sugar, baking powder.

Mix wet into dry then fold in the melted butter. The mixture will be dropping consistency.

Lightly oil a frying pan and warm over a medium heat.

Drop generous Tablespoons of mixture into the warm pan. When bubbles start to appear on the skyward side the flapjack is ready to flip over.

Cook until golden on both sides. DM/TGIFood

Become an Insider

Become an Insider