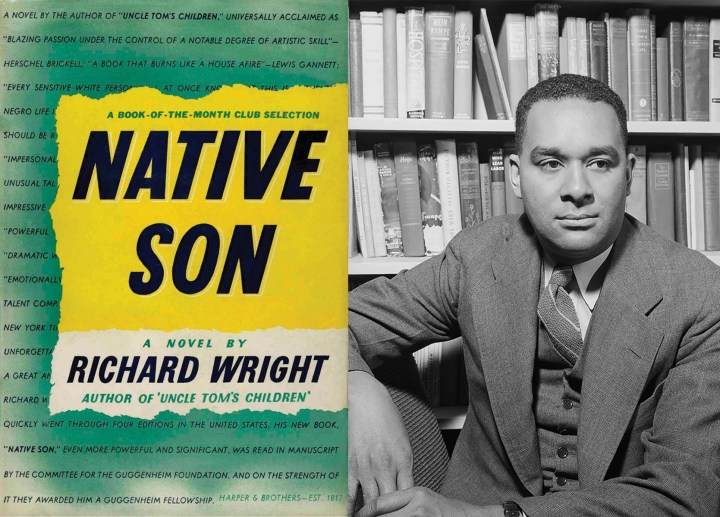

BOOKS REVISITED

‘Native Son’: A searing classic about racial violence

Though more than 80 years old, ‘Native Son’ speaks loudly to South Africans and the generation of Black Lives Matter.

When I first read Native Son, its atmosphere followed me for days. Rereading it half a century later, I again felt scorched by its dragon’s breath of burning intensity.

Richard Wright, its African-American author, died in self-imposed exile in Paris in 1960, 20 years after the work was first published.

Why review it now?

Although largely unknown in South Africa, Native Son was a publishing sensation in the US. More importantly, it passes the test for great literature: despite its shocking violence — the New Yorker wrote that it “was not for sentimentalists” — it has cast a long shadow.

The work, described by one critic as “disturbingly contemporary”, still speaks to the age of Black Lives Matter and race-haunted South Africans.

It is, perhaps, the most brutally honest fiction ever composed on the psychology of racial oppression. The Modern Library placed it 20th on its list of essential English-language novels of the last century; Time magazine included it in its top 100 novels of 1903-2005.

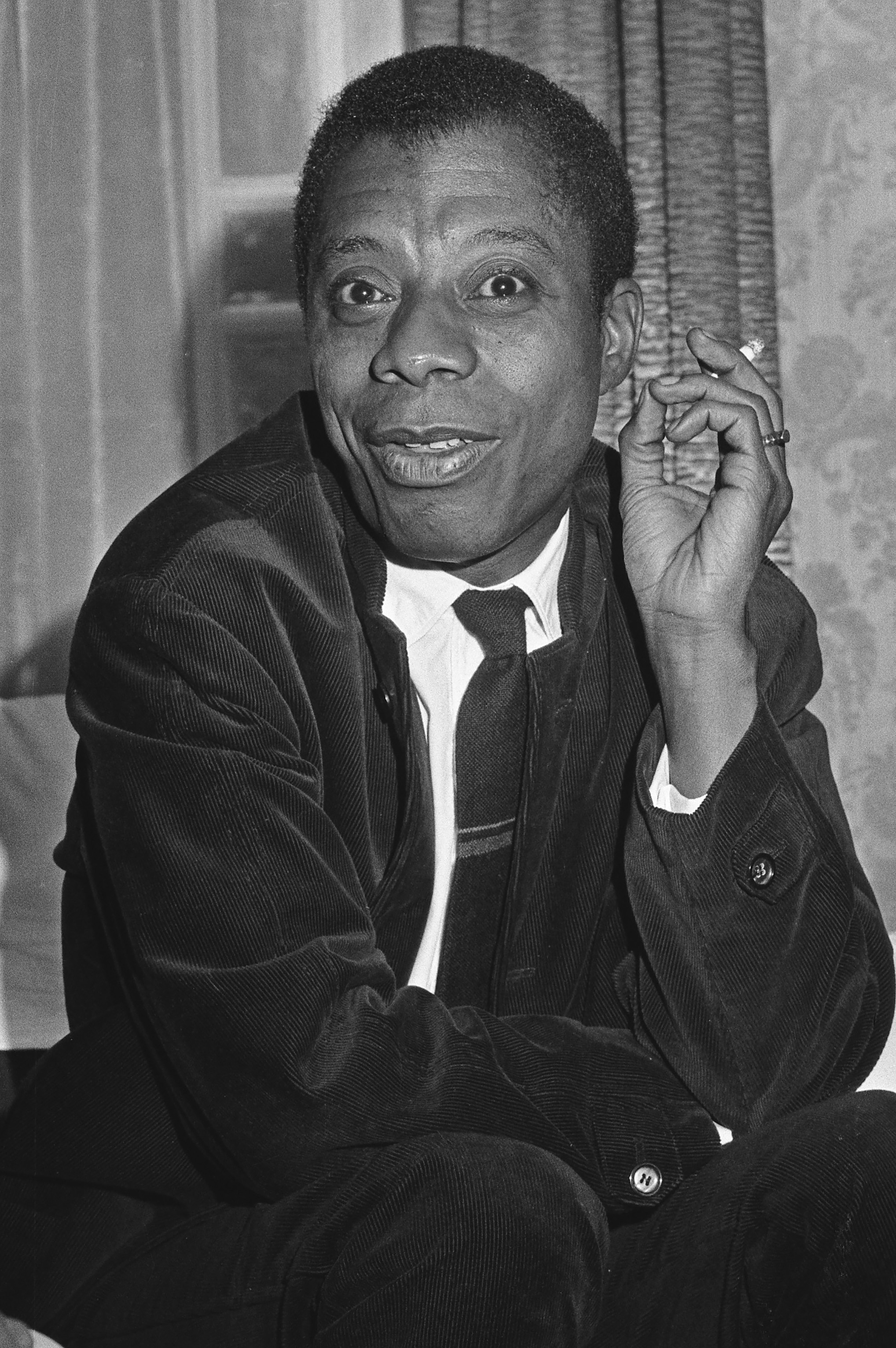

Famously, it also drove a wedge between Wright and the US’s best-known black novelist, James Baldwin, who in an essay that ruined their friendship, Everybody’s Protest Novel, attacked it as a pamphlet with cardboard characters. Baldwin later recanted, explaining that “at a carnivorous age … he had sharpened his sword to kill his literary father so that he could take his place”.

American novelist, playwright and activist James Baldwin (1924 – 1987), UK, 3rd September 1964. Image: Evening Standard / Hulton Archive / Getty Images

Born in a sharecroppers’ shack in Mississippi, Wright lived a childhood of extreme poverty, losing both parents by the age of 10. He later moved to Chicago, where, as a Post Office employee, he went to bed every night on a full stomach for the first time.

Native Son is centrally about the two cities of Chicago — its “Black Belt” and the exclusive white suburbs of the North Shore — and an explosive interaction “across the line”.

Unlike Cry, the Beloved Country, whose perspective is that of a village priest rather than his condemned son, it looks through the eyes of what in South Africa would be considered a young skelm.

Bigger Thomas is a 20-year-old petty gangster who hates his impoverished family, their rat-plagued single room and above all, the overpowering world of whites who, he tells his friend Gus, “make us live in one corner of the city” and “don’t let us do nothing”.

With bitter envy, the two men watch an aircraft in the sky. “God, I’d like to fly up there,” muses Bigger. “God’ll let you fly when He gives you your wings up in heaven,” scoffs Gus.

This is, indeed, protest writing, but psychodrama soon replaces the deadening hold of sociology. Wright points to the socioeconomic causes of violence but is more interested in its psychic roots.

Rage and fear drive Bigger: whites live “right down here in my stomach … every time I think of ’em, I feel ’em,” he complains.

He has been toying with robbing a Jewish store-owner, but is held back by “the ultimate taboo” — crime against whites, who are experienced as “a great natural force”. In a charged scene in a poolroom, he vents his consuming anxiety over the approaching heist by accusing a tearful Gus of being “yellow” and forcing him to lick the blade of his knife.

Then comes the hinge event: Bigger resentfully accepts charity from a wealthy white property developer, Mr Dalton, who hires him as a chauffeur. Dalton owns property across the Black Belt, including Bigger’s decaying tenement. But this irony is not intended as a quid pro quo for the horrible crime that follows, born of panic and fury.

Wright neither condemns nor excuses his antihero, but the portrayal of his inner life is unflinching. Bigger feels no remorse, but a “terrified pride that some day he would be able to say publicly that he had done it”.

He experiences a kind of release from fear and a strange clarity in which he sees others — his mother, the Daltons — as blinded by habit and “living without thinking”.

“The whole thing came to him as a powerful and simple feeling; that there was in everyone a greater hunger to believe that made them blind, and if he could see while others were blind, he could get what he wanted and never be caught at it.”

The Dalton crime was “the first meaningful thing he had ever done… He was living truly and deeply, no matter what others might think, looking with their blind eyes. Never before had he had the chance to live out the consequences of his actions.” To reflect such subversive thinking in the US of the 1940s, with such neutrality, took considerable literary daring.

Later, while on the run, Bigger commits a casual outrage against his girlfriend, Bessie. Decades before Frantz Fanon, Wright saw that black Americans internalised the contempt of their oppressors and projected it on to their fellow oppressed.

His sense of power is, of course, illusory. Wright divides his novel into three sections – “Fear”, “Flight” and the last, significantly, “Fate”.

Writer Richard Wright sitting at a table drinking a glass of wine, January 1951. Image: Keystone / Hulton Archive / Getty Images

The first two chapters are marked by an almost classical compression, loosely following Aristotle’s three unities of action, space and time. Bigger never leaves the stage and struggles to disentangle himself from his doom, but the Fates draw out and finally cut the thread of his short life.

Everything happens over two or three days in a symbolically icebound Chicago winter, with the climax a frantic chase over the slippery, frozen rooftops.

It has been said that in classical Greek drama the audience responds with tragic pity because the hero is felt to be superior to the forces that overwhelm him. Bigger is not a great man, like Oedipus or Lear, but we side with and pity him. In part, this is because his destroyers, the guardians of law and order, appear as more intrinsically inhuman.

The prosecutor, who is running for state office, whips up mob frenzy through a court address that repeatedly invokes the animal world and sets out to excite physical repulsion: “black mad dog”, “rapacious beast” …

Norman Mailer believed that white fear of black sexuality underpinned race prejudice; this and its alleged threat to white womanhood obsesses Bigger’s accusers. He is falsely denounced as a rapist, with animalistic references to “the marks of his teeth … on her innocent breast”. Despite everything, he retains a queer integrity — “he was lost, but would not cringe”. Pressed to confess the rape he did not commit, he refuses. And he spurns his mother’s otherworldliness and a black pastor’s pleas for him to admit guilt and repent.

“This worl’ ain’ our home,” intones Reverend Hammond in the “darky” speech of the Deep South, “ever’ day is a crucifixion.”

The same message, “steal away to Jesus”, rises dolefully from the singing of a black church. It whispers “of another way of life and death, coaxing him to lie down and sleep and let them come and get him”. He shuts his ears against the resigned enticement of the music.

The idea of eternal life is “for whipped folks,” he says — it is this life that he is groping blindly towards. Alone in the death cell, he starts to feel the desire to live.

And he glimpses the possibility of another existence. After being grilled by his left-wing lawyer, Max, when he speaks for the first time about his inner feelings, he feels the equality of a man who has something.

“He wondered if … after all everybody in the world felt alike? Did those who hated him have in them what Max had seen in him, the thing that made him ask those questions?”

For the first time, he attains “a pinnacle of feeling”, a sense that the mountain of white hatred might be others no different from himself. If that was so, “he was faced with a high hope … he never thought could be, and despair the full depths he could not stand to feel”. He sees himself standing amid a vast crowd of “…all men, and the sun’s rays melted away the many differences … and drew what was common and good upward …”

Native Son is a radical exploration of the psychology of powerlessness and chronic fear, and their links with violence. “Thwarted life,” Wright remarks, “expresses itself in fear and hate and crime.”

It is also a tragedy of lost human possibilities: “You whipped before you born,” says Bigger; his last mumbled words to Max are: “I always wanted to do something.”

The novel closes with the ring of “steel against steel as a far [prison] door clangs shut”. Beyond looms The Chair. DM/MC/ML

Drew Forrest is a former deputy editor and political editor. Native Son is published by Vintage Fiction.

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

Comments - Please login in order to comment.