AFTER THE BELL

Do we worry too much, or too little, about corporate social warriors?

Almost all corporations, at least nominally, support the notion of corporate social responsibility, and that idea is now more explicitly expounded in the idea of ESG — environmental, social and governance factors.

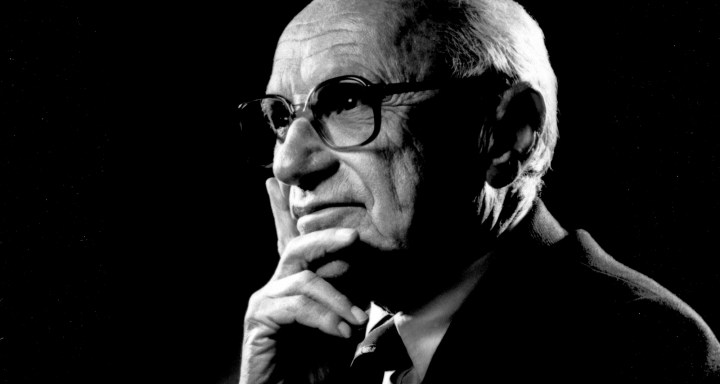

In 1970, economist Milton Friedman wrote a famous op-ed article, which was headlined “Responsibility Of Business Is to Increase its Profits”. Friedman’s view was challenged then, but is now almost universally regarded as a relic.

Very few people think in such stark terms these days. In 2019, the Business Roundtable, the premier organisation of chief executives in the US, explicitly endorsed stakeholder capitalism, putting the interests of employees, customers, suppliers and communities on a par with shareholders. The board at the time included the chairs of Walmart, General Motors, Apple and Cisco.

The tide has definitely turned, yet, it’s important to understand exactly what Friedman was arguing and why. I think the key statement in Friedman’s article is this: “What does it mean to say that the corporate executive has a ‘social responsibility’ in his capacity as businessman? If this statement is not pure rhetoric, it must mean that he is to act in some way that is not in the interest of his employers.”

Friedman used the analogy of a tax, saying if executives were acting in the furtherance of a social good, they were effectively imposing a tax on either shareholders, by producing less profit, or on consumers, by producing a more expensive product. And how were they to decide on which special social interest to spend that tax? It just made more sense and better accountability, Friedman argued, for the government to make those decisions and for business executives to refrain from making them.

Criticism

In response to the Business Roundtable statement, there has been plenty of criticism too, along much the same lines.

“Focusing on shareholder value is the highest social cause because it leads to the greatest amount of wealth creation. As corporations and their shareholders maximise wealth, resources flow into the economy in ways that necessarily increase overall social welfare,” argued George Mason University’s Professor Donald Kochan just last year.

Yet, my guess is that this view is now in the minority; almost all corporations, at least nominally, support the notion of corporate social responsibility, and that idea is now more explicitly expounded in the idea of ESG — environmental, social and governance factors.

I think the change happened for a number of reasons.

First, there has been a new realisation about the extent of “externalities”, particularly as part of climate change. Externalities are the consequence of the production of goods that result in costs to unrelated third parties. This is most obvious with the climate crisis, where climate change is the external consequence of, for example, oil companies’ narrow pursuit of profit.

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

The second reason for the change is the increased scepticism about the ability of governments to adequately deal with all the myriad challenges of modern society, which was Friedman’s solution.

Third, the democratisation of the investment sector and particularly the increase in retail investors has meant the constituency in favour of companies acting in ways commensurate with citizens’ interests has broadened and intensified.

Fourth, the investment industry, which largely represents pension funds, has an interest in extending the time perspective of corporate executives to match its longer-term obligations. It’s no accident that some of the most ardent supporters of ESG are investment houses.

But the mainstream-isation of ESG doesn’t solve all the problems, and, in fact, it does somewhat highlight Friedman’s objections.

I recently took part in a webinar on the topic of ESG (see it below) with JSE’s chief sustainability officer, Shameela Soobramoney, and Xolisa Dhlamini, a certified ESG analyst with Sanlam.

I put to them the famous recent tweet by entrepreneur Elon Musk. Musk’s company Tesla had been removed from the S&P 500 ESG Index. To Musk, this was certifiably bonkers: the whole point of Tesla is to offer a meaningful contribution to lowering greenhouse gas emissions through sustainable transport.

“ESG is a scam. It has been weaponized by phoney social justice warriors,” Musk wrote, mocking the inclusion of six oil companies on the index, and claiming that a good “ESG score” amounts to a business’s compliance with “the leftist agenda”.

Well, Soobramoney, Dhlamini and I all confessed to the social justice warrior charge.

“If we don’t have social justice, everything we are trying to build will not be sustainable,” Dhlamini said. It’s impossible to live in a country like South Africa and ignore these issues.

It all depends, said Soobramoney, on your theory of change. Different indexes are seeking slightly different outcomes, so the weighting process for each of the different outcomes does make a difference. Obviously, there are plenty of efforts to find convergence. At root, what the JSE is trying to drive is better information in the public domain, she says.

Is ESG too broad a measure?

What I wonder is whether the E, the S and the G are really compatible measures in a unitary system. Isn’t it too broad a measure to expect everything even vaguely related to corporate ethics to fit into a single box? Is it really functional to compare in the same index something as huge and as global as environmental compliance with something much more specific to a particular national and corporate context, like a company’s free float?

My other criticism goes back to Friedman’s original issue: ESG should not become a way of reducing the accountability of the government for its part of the bargain. You see this often in SA, where the responsibilities of the government are legislatively piled on to corporations. It’s a kind of backhanded acknowledgement of government inadequacy. But if that’s the case, then it’s the government’s responsibility to improve its adequacy, not hand its responsibilities to some other institution.

In any event, I think ESG is here to stay, and the next frontier is measuring it accurately and honestly, because we have a new challenge in “greenwashing”, as Deutsche Bank recently discovered.

So, in answer to the question: “Do we worry too much, or too little, about corporate social warriors?” I think the answer is “yes” in both cases. DM/BM

Comments - Please login in order to comment.