BOOK EXTRACT

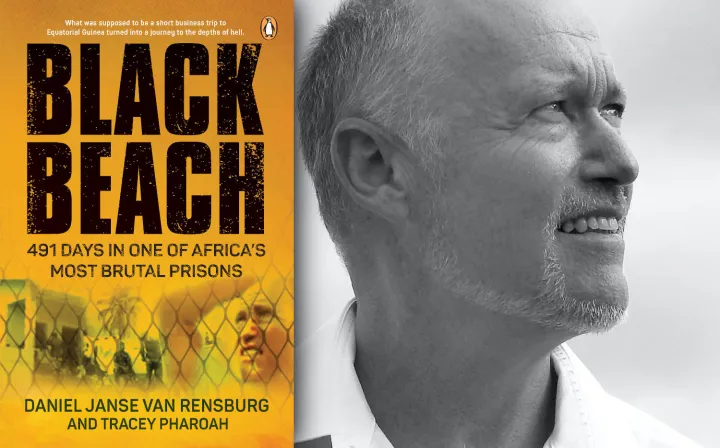

Black Beach: 491 Days in One of Africa’s Most Brutal Prisons – ‘a place of fear, torture, abuse and humiliation’

In 2013, South African businessman and consultant Daniel Janse van Rensburg set off to Equatorial Guinea for what was meant to be a short business trip. Then he was arrested.

Within days of his arrival in the country, Janse van Rensburg had been arrested by the local Rapid Intervention Force and detained without trial in the island’s infamous ‘Guantanamo’ cells. He was later illegally incarcerated at Black Beach, a prison located on Bioko island off the mainland, notorious for its brutality and inhumane conditions.

Black Beach: 491 Days in One of Africa’s Most Brutal Prisons is his remarkable story of survival over nearly two years. Read an excerpt here.

***

Until We Meet Again

Black Beach Prison, Malabo

January 2014

Over the past few days, the mood at Black Beach has been tense, and I’m filled with a sense of foreboding. My brothers who have spent years behind these walls tell me to prepare for the worst, certain that a riot is looming. Everyone is on edge, and I struggle to suppress my feelings of uncertainty.

My recovery has been slow, and although I am much stronger and getting better each day, I know that to recover fully I will need more medication, better sanitary conditions and a few decent meals. The odds of me surviving a riot are slim. You have to fight to protect yourself in a riot. The warden and prison staff are indifferent to my cause and have done nothing to aid my convalescence, most likely as per their orders from above. I know that in my present state there is no way I can fight off an angry mob, so I decide that in case things go horribly wrong, I should at least write a last will and testament, which will hopefully find its way through the prison network to the embassy in the event of my death.

Sitting in the gloom of my tent, I stare at the blank page for a long time, wondering how to put my final thoughts and emotions into words on a scrap of paper torn from a notebook. How do you say goodbye to the ones you love, the ones you have shared your life with? My wife, my children … My parents have already suffered so much, losing my brother when he was just a toddler and my sister as a young adult, and now perhaps me too. Surely this is more than one mother, one father, one family should endure?

I begin putting pen to paper, writing my name at the top of the page and addressing it to the South African embassy. I start with the practical issues, advising them that in the event of my death I want to be buried in Malabo. There is no point in adding financial and bureaucratic strain to my family’s pain and suffering by getting my remains all the way back to South Africa. I add that they will meet me again someday in heaven. I include a message of unconditional love and gratitude to Melanie, my children and my parents for being a part of my journey in this life.

It feels better to have made a start, and writing it ultimately takes longer than I anticipated. I pause often to reflect on the life I’ve had with my family, the times when we’d just talk and laugh, doing the mundane things that everyone does. All the important moments, too: getting married, seeing my children for the first time, their first day at school, school prize-giving, our dog Bubbles, bike rides in the mountains, Christmases, birthdays and holidays … There are so many precious moments that are woven together to form the tapestry of our lives, reminding me just how much I cherish every one of them. Once I’ve finally finished writing, I fold up the document carefully and push it between the grubby pages of my Bible, hoping that they will never have to read it.

I head out of my tent. If I hurry, I can join the church group in time for morning prayers and then do a mid-morning gym session at ‘Virgin Active’, followed by tea with Amadou in his cell. Although I never truly feel safe and don’t drop my guard for one moment, my life behind bars is slowly evolving. It seems that no matter where you find yourself, life takes on its own rhythm. More and more, I am discovering that finding structure in the little tasks and appointments undertaken each day brings a sense of order in a chaotic world.

But today is different. I can’t seem to shake my feeling of unease as I make my way to the cell where the church services are held. Something just doesn’t feel right. I go in and find everyone settling in for prayers. I join the circle, linking hands with the others, and bow my head, and together we recite the Lord’s Prayer. As the prayer comes to an end, we share a moment of silence, offering up our own private communion with our saviour.

The stillness is shattered by the clear sound of a name being called. Usually, a single voice would go unnoticed amid the clamour and commotion of Black Beach – the prison is so noisy that usually nothing can be heard above the din – but a strange silence has fallen across the entire prison. As I hear the name called again, my heart plummets. We look at one another in shock and the person to my left tightens his grip on my hand. They are calling for one of our Christian brothers, a man sentenced to death for witchcraft and the brutal slaying of his wife.

From the moment the first name is called, we realise what’s going on. Throughout the prison, the silence is absolute. For the first and only time since my arrival, everything stops and the inmates talk in hushed whispers. Everyone is still, contemplating their own fragility against the dark forces that control this evil place.

The next name is called and I go cold. Amadou. My barber, my tea maker, my friend. A prickling sensation runs like a million spiders over my scalp, shivers race down my spine and my skin tingles as goosebumps erupt on the back of my neck and ripple down the length of my arms. I sink heavily onto a bench, feeling weak all over, tasting bile in my throat as I struggle not to throw up. There is no way to explain the depth of my emotions. I know that Amadou has been stoic all along, accepting his fate and telling me that he is ready for his punishment, but I can’t imagine how he is feeling as he faces the reality of it in this moment, standing somewhere in the prison, hearing them calling his name and knowing that this is the end. Today will be his last on this earth.

I’ve heard that firing squads are the preferred method of execution in Equatorial Guinea and AK-47s are the weapon of choice. This shoulder-mounted semi-automatic assault rifle is simple to use and, in Africa, a popular option for the military and terrorists alike. The common AK-47 magazine holds thirty rounds. I am familiar with it on an all-too-personal level, having grown up on the continent.

My mind is a dark place picturing Amadou standing alone in front of a squad of soldiers, weapons cocked and loaded, waiting for a hail of bullets to rip through him, puncturing, mutilating, killing him. I can only pray that his death will be quick and that he won’t suffer too much.

We abandon the church service and hurry outside to join the crowd at the fence to watch as the men, seven in all, are lined up and handcuffed at their hips – a method reserved for the most violent prisoners. The guards are taking no chances as they march them out of the gate and hand them over to a group of soldiers.

As I watch the prisoners leaving, I spot Amadou. Directly behind him is Tadeo (aka Rocky), the man who almost beat another prisoner to death right in front of me on Christmas Eve. Their faces are blank, devoid of any emotion. The last thing I see as they are shoved into a truck is their eyes, downcast, as the door slams shut and the truck winds its way up the hill.

We’re all in shock. These are the first ‘official’ executions since 2010, when four political opponents were sentenced to death by a military court for treason and attempting to kill President Obiang, who himself came to power after his uncle was executed. Those men had their sentence carried out in secret within an hour of the court delivering its verdict, depriving them of their right to seek clemency or appeal to a higher court. They were denied the right to see their families, to say goodbye, just as these men that I know, men who have shared their meagre possessions with me, cut my hair and whose wisdom and generosity have kept me alive, have today been denied. Although they have done terrible things, they still have families and have been given no warning, no opportunity to communicate with them or their lawyers, no last goodbyes.

Later, as information starts filtering through the bush telegraph, we hear the gory details and are especially shocked to hear that Rocky did not die easily. The prisoners were taken to the naval facility nearby, led into the compound and lined up against a wall. At an officer’s command, the soldiers had taken aim and fired, a system bound to fail as the firing squad was untrained, overexcited, and at least a few of them were drunk. Apparently, even after being hit several times, Rocky did not go down until, finally, the officer in charge delivered the fatal shot by walking up to him and putting a bullet in his head using his standard-issue pistol. Their bodies were then loaded up and buried by soldiers at the Malabo cemetery.

A subdued atmosphere settles like a fog over the prison, and I feel an intense and overwhelming loathing for this dark and wretched place and the men that police it. It’s a cage that serves no purpose other than to breed more hatred and rage against each other and the injustices of the system, a soulless pit of sadistic cruelty and oppression where the men in charge literally have our lives in their hands.

As we turn and walk back inside, I’m distinctly aware of the heavy silence hanging over us. There is no music, no pots clattering on the cooking fires, no shouting or arguing, no youngsters playing football on the Esplanada, just an endless hush that continues throughout the day as we reflect on the fate of our friends and what it really means to be trapped behind these walls.

This is not a place of behavioural rehabilitation or skills development, unless you count apprenticeships in drug dealing, prostitution, stealing, rape and murder; this is a place of fear, torture, abuse and humiliation – a toxic mix guaranteed to poison minds and souls. As I sit huddled in my tent, struggling to come to terms with the brutal and unexpected slaying of these men and trying to make sense of things, I am willing to risk anything to get out of here. DM/ ML

Black Beach by Daniel Janse van Rensburg and Tracey Pharoah is published by Penguin Random House SA (R320). Visit The Reading List for South African book news, daily – including excerpts.

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Eeeish, Its better to just stay entirely away from doing business in certain places in the world, especially when it involves doing business with politicians.