A HERO'S LEGACY OP-ED

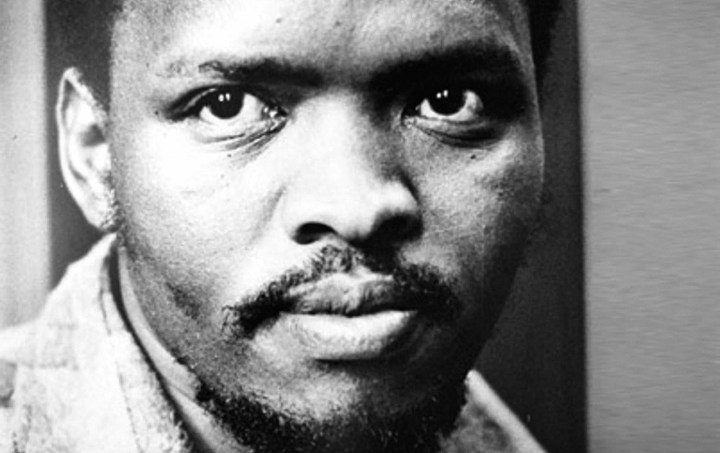

The moment Stephen Biko became a symbol in international human rights law

Stephen Biko’s death became a symbol for the debate at the United Nations on expanding the global fight against torture. His stature as a well-known civil society activist, the brutality of the murder and the apartheid regime’s attempted cover-up meant that Biko came to symbolise countless unnamed victims of similar crimes of torture and extrajudicial killings. It led to a remarkable outcome at the 1977 UN General Assembly.

Today, 12 September, marks the 45th anniversary of the brutal murder of Stephen Biko by the apartheid regime. His death caused an immediate outcry in South Africa and all around the world. His funeral on 25 September 1977, which witnessed 20,000 people marching and singing freedom songs, has been called “the first big political funeral in South Africa”.

There is no doubt that Biko’s life and death are still worth remembering almost five decades on. We can still add new dimensions to Biko’s legacy, dimensions that are worthy of our attention.

I would argue that the aftermath of his death in September 1977 can reasonably be labelled as “the Stephen Biko moment in international human rights law”. This understanding carries his legacy beyond that of anti-racism and black consciousness — which remains critically important — to also include the decadeslong worldwide fight against torture, thereby instilling his legacy with further global significance.

Biko’s death had a striking impact on the United Nations. Already on 13 September, the day after his death, the chairperson of the UN Special Committee on Apartheid issued a statement expressing his shock at the death, calling it “a crime against the oppressed peoples of South Africa and, indeed, against the United Nations”.

On 23 September 1977, the African group of states organised a tribute at the UN Headquarters in New York. UN Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim contributed a statement explaining that Biko had: “left a deep mark on the South African scene as a leader of the black consciousness movement and by his vision of an egalitarian society in South Africa. He was not only respected by the black people of South Africa, especially the youth, but made a great impression on liberal-minded South Africans, as well as many people from other countries who had occasion to meet him. That is why there is today so much grief, and so much resentment, both in South Africa and abroad.”

This was two days before Biko’s funeral. A direct statement of this kind by the UN secretary-general was noteworthy in and of itself. The UN’s high-level emphasis on Biko, however, could have ended here. Instead, it was what happened next that became the most remarkable part of the story.

At this exact point in time, the 1977 United Nations General Assembly was in session during what was a critical time for the international human rights project.

The UN covenants on civil and political rights and on economic, social and cultural rights had at long last entered into force in 1976. Alongside the UN’s International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, this gave human rights a much stronger standing in international law than ever before.

Protection against torture

However, as the United Nations struggled to find effective ways to address the gross human rights violations that were occurring across southern Africa as well as in the Middle East, Chile and Argentina, the question of ensuring adequate legal protections to prevent torture moved to the top of the agenda for many states. So did the resistance from some perpetrator states that were against expanding international legal obligations and investigatory mechanisms.

The ground was shifting but the decisive next steps were falling short. The jury was still out as to whether real progress was possible to achieve.

It was in this international context that Biko’s brutal murder entered the United Nations in an even more substantive way than the tributes mentioned above. Biko’s death became a symbol of the debate on expanding the global fight against torture. This is evidenced by a number of member states explicitly referring to Biko’s death in their statements to the UN General Assembly’s Third Committee — the committee that deals with human rights. They spoke on this under the agenda item “Torture and Other Cruel, Degrading and Inhuman Treatment or Punishment.”

The combination of his stature as a well-known civil society activist, the brutality of the murder and the apartheid regime’s attempted cover-up actions meant that Biko came to symbolise countless unnamed victims of similar crimes of torture and extrajudicial killings. It led to a rather remarkable outcome at the 1977 UN General Assembly.

Denmark was the first country that mentioned Biko in this debate. It happened in a speech on 1 November 1977 that critically self-reflected on the Nordic country’s changing approach to international human rights. As the Danish delegate explained, “In the past, his delegation had expressed its views on human rights in general, without concentrating on specific issues, such as torture. A turning point had, however, been reached in United Nations’ handling of the torture issue, which had now become a matter of moral urgency and should therefore be given top priority. If priority was not given to the issue, the general effort to promote and secure human rights might be jeopardised.”

And then he continued by weaving Biko into this equation.

“The exposure by the news media of the circumstances surrounding the tragic death of the South African youth leader, Stephen Biko, in a prison in Pretoria … had illustrated the reality behind the various reports on the practice of torture. His Government [Denmark’s] considered that the use of torture was unquestionably the most cruel encroachment on the dignity of man and on fundamental human rights and could never be justified by reference to political needs or to any form of religious or social ideology.”

The speech stated that the protection of human rights needed “legally binding conventions and appropriate instruments for international control”. It was a call for the UN to start drafting an international convention against torture.

There were 10 other countries — Syria, Sierra Leone, India, Benin, Cyprus, Liberia, Togo, China, Canada and the Netherlands — that also referred directly to Biko in this debate. Some of them linked this directly to the call for drafting a convention against torture. Others, like Canada, called on South Africa “to destroy the whole practice and philosophy of apartheid”.

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

‘The Stephen Biko resolution’

The emphasis on Biko subsequently found concrete expression jointly by the whole of the Third Committee. On 9 November, Togo presented a draft resolution to the Third Committee — backed by 15 states — that was essentially a Stephen Biko resolution. It is hard to describe General Assembly Resolution 32/65, passed in plenary on 8 December, in any other way.

Yes, the resolution condemned the South African regime for the deaths of detainees, police brutality, torture and violence against peaceful demonstrators that defined the apartheid. However, it did this through repeated mentions of Biko.

First, the resolution declared that the General Assembly was “deeply shocked by the cowardly and dastardly murder in detention of Stephen Biko”. Second, the General Assembly “strongly condemns, in particular, the arbitrary arrest, detention, torture which led to the murder of Stephen Biko by agents of the racist minority regime of South Africa”.

The resolution concluded with the following paragraph where the General Assembly: “expresses its conviction that the martyrdom of Stephen Biko and all other nationalists murdered in South African prisons and the ideals for which they fought will continue to enrich the faith of the peoples of southern Africa and other parts of the world in their struggle against apartheid and for racial equality and the dignity of the human person”.

That paragraph was drafted in a way that still speaks to us today, 45 years on. It should be noted that it is extremely rare that the UN General Assembly passes a resolution focusing on a single person — even more so when the person in question is a young civil society activist. I cannot remember seeing this in 12 years of doing research on UN history. This makes GA Resolution 32/65 a stand-out UN document. It still deserves, however, to be put in the proper historical context.

The Biko resolution came out of a rich General Assembly debate where attention had also been paid to a “code of conduct for law enforcement officials” and where medical ethics for doctors in the context of torture had also been raised — two issues that were also critical for the Biko case (and remained so for decades after his death with attempts to bring those responsible for his murder and its cover-up to justice).

The Biko resolution was passed alongside three other resolutions under this same agenda item. The first of these resolutions finally secured the backing for the United Nations to begin drafting an international convention against torture. A decision on this had been one of the major human rights battles at the UN during the 1970s.

The decision would prove a turning point for the international efforts to combat torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, despite negotiations on the convention taking seven years until its adoption in 1984. The significance of this adoption cannot be adequately presented here, but the convention did, for example, determine universal jurisdiction as a principle in international law.

The 1977 decision also helped facilitate a change in the UN’s approach to human rights violations from a more selective approach — where it was only politically possible to focus on a limited number of violating countries — to a more universal approach that focused on violations where they happened. This was a major change — also backed by parallel work on enforced disappearances — and the significance of this should not be underestimated.

It was a historical turning point that had the imprint of the Biko case all over it during the decisive weeks and months in late 1977. This is why it is fair to label this “the Stephen Biko moment in international human rights law”. The role that Biko came to play at this pivotal moment in the UN debate on torture was clearly beyond his own control, but it still forms part of his legacy.

This moment reflects what he fought against and why he died. His role here was symbolic but also visceral because his brutal death helped make the international community more fully aware of the barbarism not just of the South African regime but of torture as a global practice of states while finally reaching a point to be willing to act on this more concertedly.

That makes the story of this global historical moment relevant today when remembering Biko on the 45th anniversary of his death. His legacy is perhaps more widespread than we think and where our imagination has taken us. The Stephen Biko moment in international human rights law is something we have been building on for 45 years. Today, we should acknowledge this foundation — even if it was birthed in pain, suffering and devastating loss. DM/MC

Steven LB Jensen is a senior researcher at The Danish Institute for Human Rights. He is the author of the prize-winning book The Making of International Human Rights. The 1960s, Decolonization and the Reconstruction of Global Values. His most recent publication is the co-edited volume Social Rights and the Politics of Obligation in History. He is currently working on a history of social and economic rights in 20th-century international politics.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.