MATTERS OF OBSESSION

A stitch in sacred time – exhibition weaves our oceans back into the realm of the divine

A far cry from the traditional fist-pumping activism of the past, this vibrant exhibition expresses narratives about the sacred relationships with the sea.

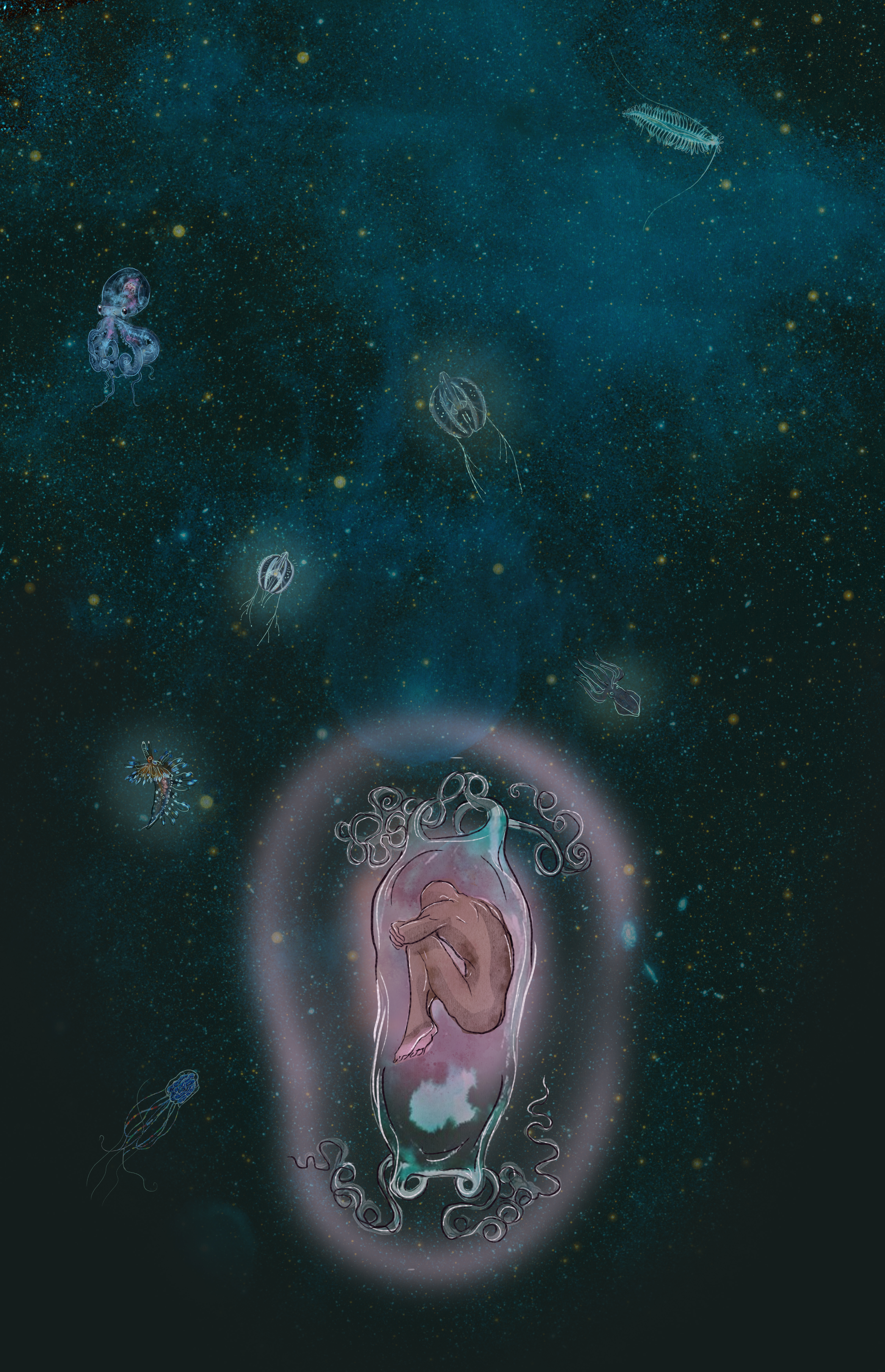

The bloom and thrust of the vibrant – and sexily suggestive – artwork titled The Crochet Coral Reef, with its bobbing penile and frill-lipped labial constructions, was 12 years in the making. Showcased in the exhibition Our Ocean is Sacred, You can’t Mine Heaven, it is a wonder to behold.

Lighting up Zero Gallery, this crocheted frenzy of lip and tip is as tall as a wall and wider than a corner. The Crochet Coral Reef has what James Joyce called “aesthetic arrest”, or in layman’s terms, the wow factor. It’s a magnet to the curious gazes of passers-by, from children, lawyers, car guards, unhoused people, priests, to informal traders. Stopping them mid-sentence – like a siren luring a lonely, horny sailor with her song, and inciting the lust of many who longed for a pattern for these undulating marine creatures so they too can stitch their own. Bear in mind that many people have never seen (and will never see) the beauty of an underwater coral world. But this is only one artwork on exhibit.

‘Our Ocean is Sacred, You Can’t Mine Heaven’ exhibition. Image: Jhono Bennett

In many traditional myths, the world was woven into being. The Hopi Spider woman sang the world into existence. The thread of life was spun on the spinning tool of the Ancient Greek Moirai or three fates who controlled destiny, as did the Norse fates. The Ancient Egyptian word for being and weaving share the same root. And on our own continent there is Anansi the storytelling trickster spider god from West African mythology who is also regarded as a resistance figure and precursor of the spider man.

We’ve been stitching since palaeolithic times when we roamed Earth as hunter-gatherers, in a time when we lived as a part of the natural world. Before we took the fateful fork in the road and settled when our mindset underwent a tectonic shift, and we began to act as separate from and in charge of the natural world. The outcome: domination and ownership. Of nature, livestock, women and children, and other people. A bitter harvest that we are currently reaping.

‘Our Ocean is Sacred, You Can’t Mine Heaven’ exhibition. Image: Dylan McGarry

This is an intense, dense, multifaceted, integrated affair conceived fittingly in waves. Or as lead curator Dr Dylan McGarry says, it’s “an exhibition of many parts” and one that finds itself perfectly placed in our current climate of brutal seismic surveys off the Eastern Cape’s Wild Coast by Shell and the pushback by communities who recognise not only the irreparable harm to the environment and livelihoods but also to the cultural and spiritual practices of communities. Any economic expansion needs to honour the experiences and knowledge of customary rights holders. This approach to the ocean as a commodity has its roots in the colonial concept of terra nullius, nobody’s land or wilderness where land deemed unoccupied, or not recognised as belonging to a sovereign state and was regarded as up for grabs. So that the ocean, like outer space, “is seen as the next frontier and in many ways, it’s become the next frontier in colonial practice and materialism”.

This exhibition talks in particular to the spiritual practices of people. In this interpretation, the ocean is not just a place of recreation and resource but a place of the divine and the sacred. In keeping with honouring the sacred, each work in the exhibition expresses narratives about the sacred relationships with the sea.

Scene H. Image: Dylan McGarry

The first wave includes: The Crochet Coral Reef from the Woodstock Art Reef Project which was begun by Maria van Gass and Leonie Hofmeyr and inspired by the Wertheim sisters; the Tapestry: Our sacred Ocean a massive dream catcher-type structure that references the map tables used to carve up Africa during the Berlin Conference (1884-1885) made by the Keiskamma Art Project; Emptheatre’s The Blue Blanket, a short movie which explores the impact of oil and gas exploration on our oceans, referencing the spiritual; Songs of the Ocean comprises two audio projects, Songscapes and Stories, focusing on the role the ocean plays in Xhosa music and storytelling. Cleo Droomer’s (Life) Jackets, Intangible Heritage fashioned from fabrics from his family’s past, flotation devices that bring to the surface haunted histories of oceans and slavery; Intangible Heritage is an exhibition of photographs that encompass heritage and spiritual practices associated with the ocean, curated by Luke Kaplan; Purification is an installation using antique chemistry beakers and seawater used in an “ukubuyisa” ritual by Dr Dylan McGarry. A theatre project by Empatheatre titled Lalela and uLwandle. And Aaniyah Martin’s Hydro-rug featuring collaborative stitchings of Brown and Black histories into a rug.

‘Our Ocean is Sacred, You Can’t Mine Heaven’ exhibition. Image: Jhono Bennett

‘Our Ocean is Sacred, You Can’t Mine Heaven’ exhibition. Image: Jhono Bennett

Aaniyah Martin with her Hydro-rug. Image: Traci Kwaai

Martin will also be “rewalking” the coastline at full and new moon, gathering debris to rework into collaborative artworks. Her “artwalk” echoes author Ursula K Le Guin’s The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction which posits that even before the masculine spears appeared in our evolution there was the feminine carrier bag, which some considered our ancestors’ greatest invention. Martin’s rewalk is an antihero’s journey or rather a heroine’s journey which is not so much getting from A to B but rather the journey itself. Le Guin’s Carrier Bag Theory suggests that all heroes were at one point contained in carrier bags whether in their mother’s womb or in a carrier bag, in other words, carried by the feminine. And it’s this vulnerability, this defenselessness, this dependence on a woman which McGarry points out is always the part left out of the hero’s journey and one which Martin’s rewalk seeks to readdress.

Our Ocean is Sacred, You can’t Mine Heaven has its roots in an outreach to organisations by One Ocean Hub in an attempt to better understand our “intangible heritage” and the sea and how we humans can make better decisions. The overall ethos of the exhibition is a far cry from the traditional fist-pumping activism of the past. Instead, it reflects the gentler, post-activist approach of Nigerian philosopher, writer, activist and professor of psychology, Dr Bayo Akomolafe, who said:

“In these times of weaponised fundamentalisms, depleted philanthropic coffers, tired policy-makers and exhausted policies, waning trust in establishment politics, colonial knowledge and painful interpellations, touchy skins, and prickly attitudes, it’s probably wise to retreat. To seek sanctuary. To heed the call of the edges. The edges in the middle.”

‘Our Ocean is Sacred, You Can’t Mine Heaven’ exhibition. Image: Dylan McGarry

From the exhibition’s earliest curation stages, Akomolafe’s post-activist approach of creating sanctuary informed the discussions. Lead curator McGarry explains how the exhibition follows Akomolafe’s thinking of how “in the height of urgency and difficulty we need to slow down and create spaces of refuge”; or what the multispecies ecofeminist theorist and Professor Emerita in the History of Consciousness and Feminist Studies departments at the University of California, Donna Haraway, refers to as “staying with the trouble”. McGarry goes on to explain that according to Akomolafe spaces of refuge or sanctuary refer to the space that sits between patriarchy and capitalism, a space that encourages “people to come together carefully and gently with each other and actually just sit with the problem”. It’s a wonderfully counterintuitive approach, the antithesis of the masculine and a celebration of the feminine as inclusive and collaborative.

McGarry explains that Our Ocean is Sacred, You can’t Mine Heaven is structured in three parts. One part is a public storytelling project, one part an archive of new customary rights evidence, and one part the creation of a space for various contributors to spend time together with no other agenda than to build relationships and shift the narrative in all its nuances of the “conflictual, messy, emotional, spiritual or esoteric”.

‘Our Ocean is Sacred, You Can’t Mine Heaven’ exhibition. Image: Dylan McGarry

While there is no doubt about the beauty of some of the exhibits, McGarry has what he calls a “critical relationship” with beauty, aesthetics, and art believing that artworks should be instruments for consciousness. For McGarry the artist’s job is to wake up and in turn wake others up too.

The goal for the space over the next five months is to be “multidenominational, multispiritual worldview space for people to come together and share how the ocean is sacred to them in an “embodied” way. The exhibition space expresses a wish and a hope to create a sanctuary in which you can move between doorways of knowledge systems, all of which are speaking to the ocean as sacred and are sacred for many different reasons”. As McGarry points out, what is sacred to a traditional Xhosa healer is very different to an African Zionist, small-scale fishers, or artists like Aaniyah Martin – hence the title Our Ocean is Sacred, You can’t Mine Heaven.

The exhibition is also a love letter to the small-scale fishers who are the defenders of the ocean from the bullying tactics of those in positions of power and powered by greed. DM/ ML

Our Ocean is Sacred, You can’t Mine Heaven is a radical “an-archive” on intangible ocean heritage and a multigenre exhibition raising consciousness and celebrating the sacredness of the ocean. It’s on at Zero Gallery, corner of Church and Berg streets, Church Square. It was made possible by the support of EITZ, the One Ocean Hub’s Deep Fund, and the National Arts Festival 2022; co-curated by researcher, educational sociologist, and artist Dr Dylan McGarry, ethnomusicologist Dr Boudina McConnachie from the International Library of African Music, artists Michaela Howse from the Keiskamma Art Project and Luke Kaplan from Coastal Justice Network. The exhibition ends on 20 November 2022.

In case you missed it, also read The Unpacking of Janjaweed (devils on horseback), a sculptural assemblage by Kevin Brand

The Unpacking of Janjaweed (devils on horseback), a sculptural assemblage by Kevin Brand

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

I love this article. As a History teacher, I did an elective for gr 8 pupils on Hydro colonialism/voices across the ocean. I explored the spirituality of the ocean, the people who became victims as slaves, or identured labourers being carried across the dark waters, the current pollution – form plastic to noise from shipping, and the recent ceremonies carried out by communities, to honour their dead. At the end, the pupils wrote poems and they displayed a remarkable synthesis of the different aspects of why the ocean should be revered and protected. Prof Isobel Hofmeyr came and spoke about hydrocolonialism,and artists’ work in the ocean. Joanne Joseph spoke of the passage of indentured labourers across the ocean and the consequences. Finally my pupils spoke to pupils across the Atlantic ocean, in a school in Connecticut, and exchanged what they knew of slavery and its legacy. Creating their own voices across the ocean. Just another attempt at integrating education, spirituality, art, history and literature.