THE LAST SOVIET PRESIDENT

Mikhail Gorbachev (1931-2022): The mysteries of a revolutionary reformer revealed in death

Former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev has died three decades after he lost power, even as the reforms he initiated led to unimaginable changes on the international scene.

Just short of his 92nd birthday, the former leader of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev, died on 30 August 2022. His career had carried him from the obscurity of a poor, rural childhood to the pinnacle of the Soviet Union’s most powerful position. Ensconced in the corner office of Moscow’s Kremlin, he led what ultimately became a doomed effort to reform and revitalise the creaking Soviet system.

Former US president George HW Bush (left) and former Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev (right) during their meeting in Moscow on 23 May 2005. EPA-EFE/SERGEI CHIRIKOV

His reforms ultimately helped set off an economic free fall inside the Soviet Union/Russia and a chain of events that ultimately cleared the way for the ascension of Vladimir Putin as Russia’s president. But along the way, to his great credit, Gorbachev took those extraordinary, decisive steps — with US presidents Ronald Reagan and George HW Bush and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher — to bring the Cold War to an end, without bloodshed. For that, if nothing else, the world must be forever grateful.

The change of heart by the Soviet government, along with Gorbachev’s reforms, also ended up allowing the peoples of Eastern Europe to shuck off the repressive hold the Soviet Union had on them since the end of World War 2. That loosened straitjacket, in turn, opened opportunities for the respective rising nationalisms of the 14 other Soviet republics, besides Russia, to declare their independent statehoods, thereby bringing to an end the Soviet Union that had been heir to the earlier czarist empire.

Gorbachev was born and raised in the deep poverty of the southern Russian countryside in 1931, before attending Moscow State University to study law in the years soon after World War 2. Entering government, he rose steadily through the ranks of the Communist Party and government (the two were tightly linked, of course, for anyone harbouring ambitions to ascend to greater power) and eventually he was promoted on to the party’s Central Committee.

By the time he reached the top of the pyramid in 1985 in the aftermath of the sclerotic premierships of Yuri Andropov and Konstantin Chernenko, he represented a new generation of politicians and savvy bureaucrats, years younger than the many politicians, bureaucrats and generals Gorbachev rusticated or retired from service once he had the power to do so.

Already by the early to mid 1980s, Gorbachev seemed to have come to the realisation that the Soviet Union, as it was then constructed, would be increasingly unable to compete successfully against its western antagonists.

He correctly saw this competition as a multifaceted one comprising the need for national economic growth, technological development and military spending, as well as the challenges to international political order as the Soviet Union continued to suppress its increasingly restive empire in Eastern Europe.

Afghanistan and Chernobyl

Moreover, there was also the Soviet Union’s catastrophic intervention in Afghanistan, a brutal war that had been ongoing since 1979. By the time it ended in 1989, some 15,000 Soviet military personnel had died trying, unsuccessfully, to support a communist government in Kabul. And, of course, there was the effect on public trust (and international regard) in the Soviet system from the explosion at the Chernobyl nuclear plant.

By 1985, when he had become the Soviet leader, he was already looking for ways out of the morass he realised his nation was in, as its citizens yearned for more and better quality consumer goods, along with the liberalisation of artistic, cultural and communications freedoms.

In response to these challenges, Gorbachev conceived the initiatives of glasnost and perestroika — openness and restructuring — to attempt to meet the growing hunger for goods and services, and a more open cultural world, as well as better and more effective access to an often-impenetrable government decision-making system.

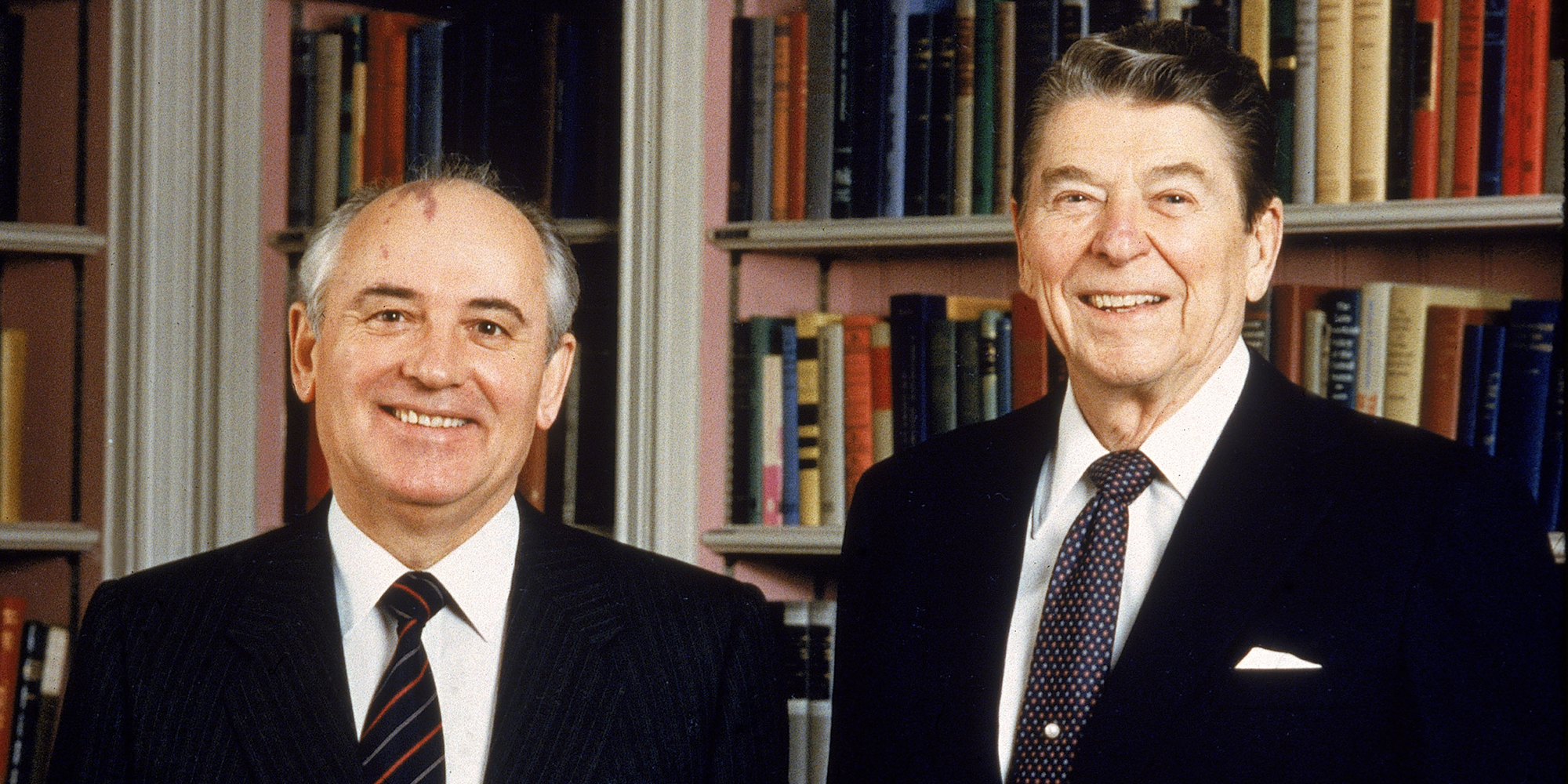

Concurrently, he recognised there was an opportunity to renegotiate the terms of the accelerating, increasingly ruinous arms race of the Cold War that presented itself through the persons of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher (she had apprised Reagan that Gorbachev was someone they could do business with). Following several one-on-one summits with Reagan that did not follow the usual formulas, the two achieved agreement on the withdrawal of an entire class of intermediate range nuclear missile weaponry from Central Europe — somewhat to the surprise (and even dismay) of some officials on both sides. Through those acts, it became possible to see a world without the constant escalatory cycles of the East-West arms race.

Back in the early years of his rule, Western opinion among Russian specialists was optimistic about his efforts. For example, American scholar Peter Juviler and Japanese expert Hiroshi Kimura, in a joint introduction to a collection of international studies entitled “Gorbachev’s Reforms”, would write in early 1988:

“The evidence seems pretty clear that Gorbachev intended his reforms not to be primarily a public relations stunt, for all the media ballyhoo about them, but rather, a means to preserving the status of the USSR as a world power into the 21st century.”

But in the meantime, those other pressures for change were unrelenting. The slow-motion resistance by Eastern Europeans and the beginnings of a deeper rebellion against the Soviet satellite regimes of Eastern Europe was picking up steam. The Solidarity labour movement in Poland was gaining popular support (bolstered by the Catholic Church and the pope’s visit to Poland). Then the Czechoslovak and Hungarian regimes both declined to stop East Germans desperate to visit or emigrate to West Germany from crossing their borders en route to Austria, and then on to West Germany.

Berlin Wall breached

Moreover, pressures were growing on East Germany to end its strict border controls for direct passage to the West, and the Berlin Wall was eventually breached by eager Berliners on 9 November 1989. On that night, the regime’s border guards simply declined to stop East Berliners from crossing through the border gates.

Then US president Ronald Reagan (right) poses with then Soviet Union president Mikhail Gorbachev in the White House library, Washington, DC, on 8 December 1987. (Photo: White House Photos / Getty Images)

Ultimately, in a response to Ronald Reagan’s widely remembered 1987 call during his visit to Berlin for Gorbachev to tear down the Berlin Wall, Gorbachev himself stated that the Soviet Union would no longer attempt to bolster the satellite regimes, if they could not maintain the backing of their people.

There would be no events like Berlin in 1953, Hungary in 1956 or Czechoslovakia in 1968. Suddenly, from Poland to Bulgaria, all those regimes imploded, largely bloodlessly, save for the Romanian one, where Nicolae Ceaușescu and his wife were sentenced to death and executed.

By then, nationalist pressures within the Soviet Union were increasing as well, as the Baltic republics, then the rest, from Ukraine to the Caucasus and Central Asian republics, were beginning to search for a pathway towards independence. At this point, the old guard’s response to Gorbachev’s economic restructuring and the political and social disruptions of glasnost led some Russian generals to attempt a coup d’etat against the president while he was resting at a Black Sea resort, working on a major speech.

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

Boris Yeltsin

The poorly planned coup failed, but not before Boris Yeltsin, a political supporter of Gorbachev, was able to lead a popularly backed resistance to the plotters and their tank forces, famously clambering atop a tank to lead those opposing the coup. But the ultimate result was the full collapse of the Soviet Union into the 15 separate republics — and the end of Mikhail Gorbachev’s political power just a few months later, once the country he was president of no longer existed.

On a personal note, the writer’s family — just as those events were taking place inside the Soviet Union — was on vacation in the Kruger National Park. This was before cellphones, and the rented car’s radio was a seriously reluctant bit of poorly performing gear. We went into the park, enjoyed ourselves, watched cheetahs catch a buck right in front of us, saw all the Big Five (minus a leopard) and enjoyed our time thoroughly. But once we left the park, the radio suddenly sprang to life and we heard our first newscast in a week — learning that a coup against Gorbachev had failed and it seemed the Soviet Union itself might be about to disintegrate.

It was a lesson in the potential fragility of a nation’s unity that we could not forget. Given South Africa’s contested circumstances at the time, we could only wonder what was next for this place. And it was almost certainly true that the opposing elements of South Africa’s own shifting political world were astounded, and taking careful notes about what was happening in a big, powerful nation with an imposing military.

Vladimir Putin

In an irony of history, Yeltsin’s power grab eventually led to his promotion of a former KGB operative — Vladimir Putin — a man who had witnessed first-hand the collapse of East Germany. Putin, of course, would in time replace Yeltsin, with all that such a power grab meant for Russia and the world.

Looking back at that dissolution of the Soviet Union, Putin would cite it as the biggest catastrophe of the 20th century, placing the blame for that extraordinary collapse firmly on Gorbachev and all his works for this outcome. And that view led Putin’s Russia to its invasion of Ukraine.

Of course, Gorbachev’s economic reforms also had their share of problems. There were major dislocations and price rises, job losses and the collapse of various state enterprises, as well as triggering the rise of the oligarchs as they carried out their seizures of major chunks of the formerly government-held economy — especially in the primary commodities — amid the spiralling chaos.

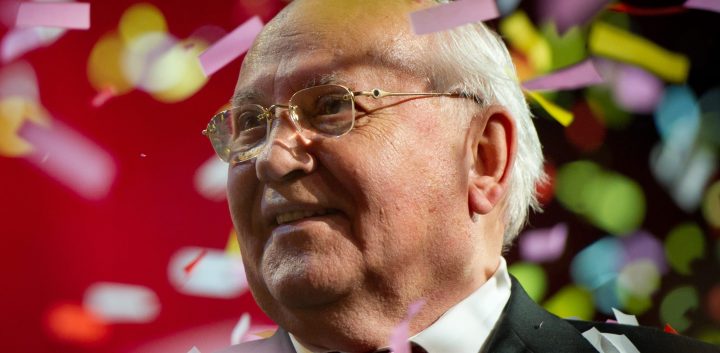

Towards the end, in various public events inside the country, Gorbachev was even booed by marchers who clearly placed the blame on him for the circumstances — actions virtually unheard of in Soviet life previously. Despite this disdain domestically, Gorbachev’s international reputation had continued to grow as outsiders saw him as a man carrying out the Herculean task of recreating his nation.

Post presidency

When his political power had vanished, Gorbachev moved on to become a fixture of the high-level international conference circuit; an author of well-received memoirs, the founder of various foundations and institutes focusing on important international issues, as well as a foundation dealing with cancer — a personal response to the passing of his wife, Raisa, from that disease.

Subsequent to his fall from power, unlike the standard practice of so many authoritarian regimes, Gorbachev was never treated to arrests, imprisonment or public humiliations. Instead, in his daily life, he received petty insults such as the replacement of the state-supplied limousine in recognition of his status as a former president — with a standard sedan. And he certainly was not invited to the swankiest parties in the Kremlin or the flashy, vulgar ones hosted by the nouveau riche oligarchs either. This was despite the reality that his reforms had actually opened the gates for their newfound acquisitions.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel and former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev attend the opening of an exhibition on Gorbachev’s life at The Kennedys museum on 24 February 2011 in Berlin, Germany. (Photo: Henning Schacht-Pool / Getty Images)

But even as his reputation in Russia sank, his approval continued to soar abroad with many. He had been a Time magazine Man of the Year and had won a Nobel Peace Prize. It was often said, based on his international reputation as a clear-eyed yet inspirational reformer, that he could have been elected president of practically any country on the globe — save Russia.

A comparison with FW de Klerk

Gorbachev’s rise and fall cries out for comparison with the fate of another leader closer to home for South Africans. That, of course, would be the circumstances of the late South African president, FW de Klerk.

As South African political scientist Peter Vale (a senior research fellow at the Centre for the Advancement of Scholarship at the University of Pretoria and a visiting professor at the Federal University Santa Maria in Brazil) described it, “Both (were) young (and) ambitious; both lawyers; both positioned at a key moment in history; both probably recognised that this demanded a risky decision; both knew that their respective parties were moribund and intellectually weak; both probably were encouraged by (western) interlocutors that market-inclined discourse would carry their respective choices.”

Once both leaders had made their respective decisions to force political change (and in Gorbachev’s, major economic reforms as well) there was no turning back, even as there was probably not an initial realisation that they would be unable to control the unravelling of their respective earlier systems.

American scholar Elaine MacKinnon, examining the two men’s choices through a study of their memoirs in, “Grasping at the Whirlwinds of Change: Transitional Leadership in Comparative Perspective. The Case Studies of Mikhail Gorbachev and F.W. de Klerk”, had written that both men could “… initiate monumental change in their respective systems, but then could not hold onto power in the new political environments they helped to create.

“Each thought that he could construct a system that could blend old and new without negating the entire legacy of the past. Yet, each reached a point where the momentum of change pushed beyond the limits of his outlook and experience.

“What made Gorbachev and de Klerk able to launch change in the first place eventually made it difficult for them to function as leaders for the new age and made it difficult for people to accept them as such.”

At least for Mikhail Gorbachev, it is possible that at some point in the future, once Vladimir Putin’s terrible revanchist dream ends, there may yet be a newfound respect for the “revolution” that Gorbachev brought to life — and maybe even a monument in his honour.

Maybe, this second time around, Russians will embrace a new chance of a more democratic and open state, without the worst excesses of Putin’s authoritarianism and its military misadventures, and the rapaciousness of the oligarchic class.

The world can but hope. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.