What we’re watching

Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power — a documentary analysis of the male gaze in film

Director Nina Menkes’ ‘Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power’ – now screening at Encounters – uses clips from 1896 through to the present to examine how the visual language of cinema is interlinked with a global culture of discrimination in the workplace and sexual abuse.

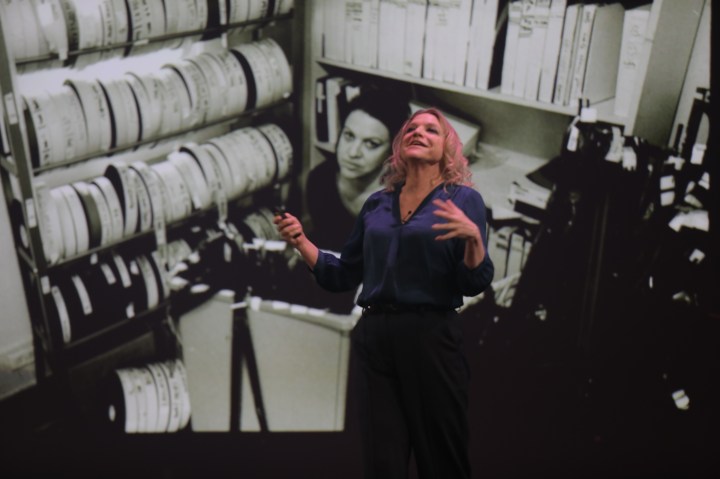

Nina Menkes’ documentary feels a lot like a TED Talk without a time limit that got a cinematic facelift. Large portions of the documentary are made up of clips from famous films and interviews with a host of female theorists, actresses, directors and psychoanalysts; but the footage that guides the narrative takes place in an auditorium with a sauntering Menkes presenting to a large audience.

Her overarching theory of cinema is built around the work of “the original gangster film theorist”, Laura Mulvey, whose 1975 paper Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema popularised the concept of the male gaze and helped form a framework through which films are still psychoanalysed today.

Mulvey herself does pop up briefly as a talking head to explain her belief that part of her pleasure of watching movies as a young person came from her watching them as if she were a male spectator. Menkes reiterates this idea constantly throughout the presentation: “Through time, the woman’s body becomes more and more sexualised but the basic structure of looking remains the same. This visual language dictates to us ways of seeing that are so specific that it almost feels like a law.”

Other professionals in the film sum up how these ways of seeing are damaging with potent clarity: “In a visual culture such as ours, in which there is a ravenous appetite towards the female as object, if the camera is predatory, then the culture is predatory as well.”

The simplest and most ubiquitous way that people tend to think about sexism in film is how power is reflected in the writing of characters of different genders — whether a woman or a man is cast as a labourer or a CEO and whether their dialogue implies helplessness or agency and capability. This inequality in the writing of characters is one of the easiest things to change about a film while still conforming to male-centric film culture, which is why even superheroines like Wonder Woman and Black Widow still perpetuate the objectification of women despite their characters having been written as powerful.

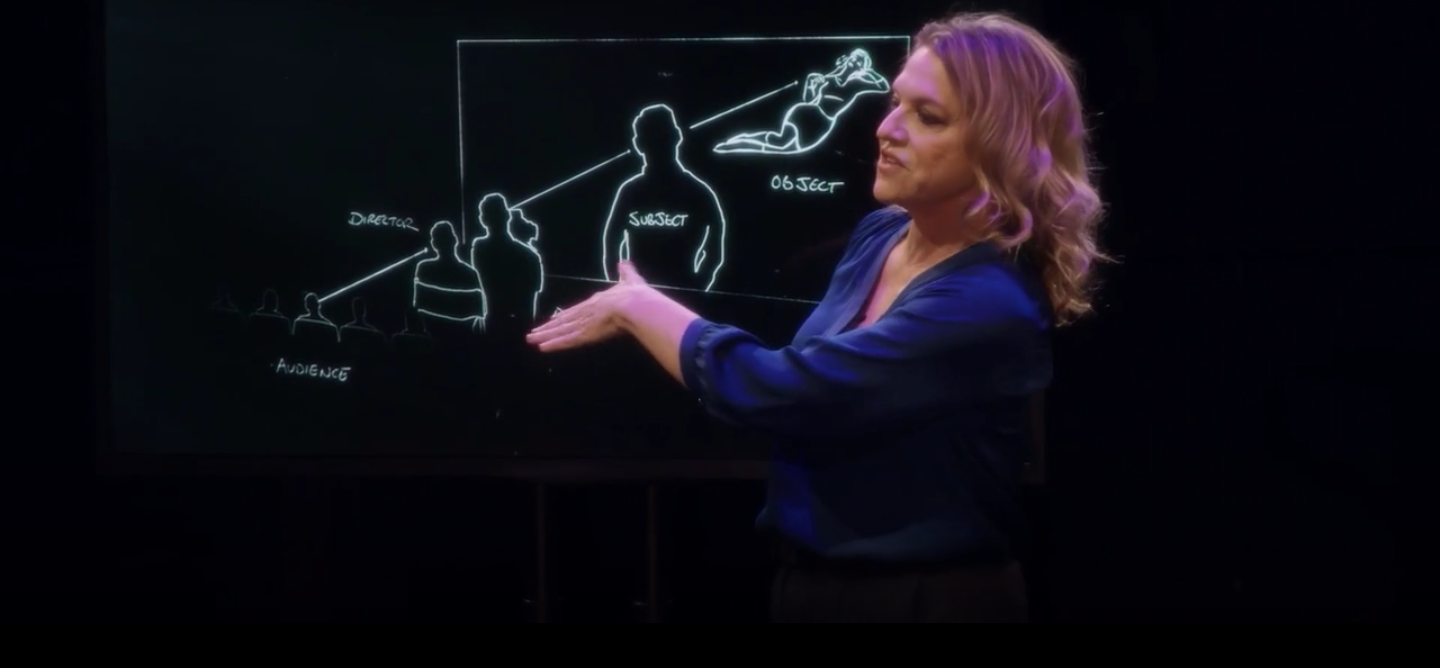

Menkes barely touches on this type of inequality — her interests are subtler and more technical. She starts by assessing how shot design is gendered — the ways in which lead actors and actresses are filmed differently.

Because the vast majority of people in powerful positions in the production of a film are typically male, it’s unsurprising that films often assume a male point of view. The positioning of the camera to suggest a man’s perspective tends to make a woman the object in a scene rather than the subject, even when she is written as the main character.

Even films that contend to be speaking out about the objectification of the female body often employ traditional sexist cinematography and benefit from the gratification of the male gaze. The example given in Brainwashed is Bombshell, an ostensibly feminist 2019 film that rode the “Me Too” wave. It’s about women who are sexually harassed on the job (at Fox News) and take their abusers to court, yet the sexual harassment depicted in the film is still shot from the harasser’s point of view.

Menkes draws upon trope camera techniques that have been used over and over in history indicating the differing ways in which a female character should be seen in contrast to a male character; for example, the filming of fragmented body parts or immobility of a woman during a scene.

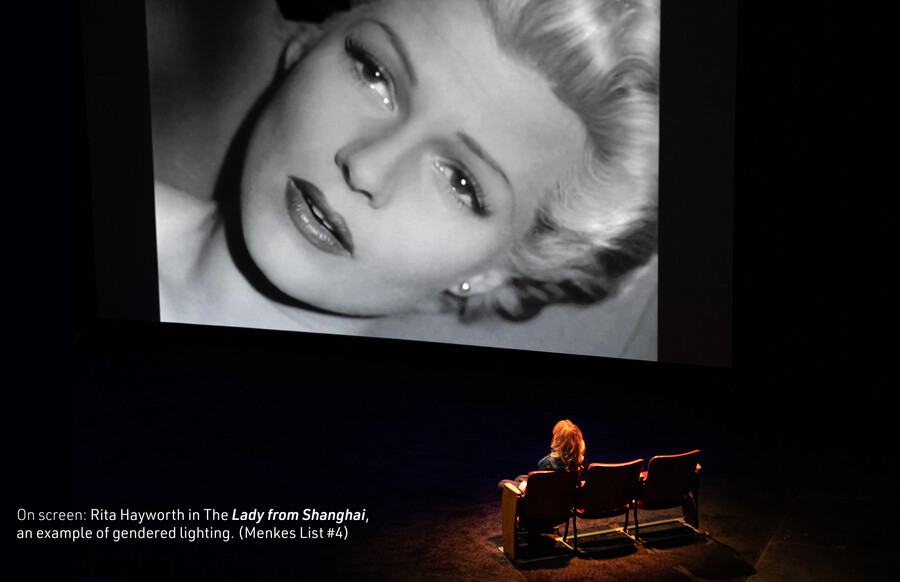

Menkes notes how gendered use of camera movement shows how characters are to be valued, with body pans and slow motion being used on women for the purpose of sexualisation, while for men, slow motion is typically reserved for action military shots. She even suggests that lighting is gendered in film – a more abstract concept that points out how (especially in early films) men are often lit three-dimensionally and positioned in a real space, while women are lit two-dimensionally with abstract backgrounds.

“Camera design is not just optical, it’s perceptual, so that you aren’t just seeing what the character sees, you are aligned with them emotionally and in their thought process,” she says.

Menkes demonstrates these concepts with hundreds of clips from well-known films, which are accompanied by a grand and disquieting score that would suit a psychological thriller. Because of its focus on the objectification of women in film, Brainwashed features a lot of graphic nudity, and its ideologically loaded stylisation puts the viewer on edge. This turns previously familiar scenes designed to be pleasing to the male gaze into disturbing sites of insidious sexism.

Production still from Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power. Image: courtesy of Encounters Documentary film festival.

The constant mirroring of the dialogue with clips from the annals of movie history manipulates the viewer to notice their silent misogyny in exactly the way they are usually manipulated not to notice it. It’s uncomfortable for a viewer of any gender to realise how many techniques of sexualisation we have all internalised and taken for granted.

Menkes seems determined to regulate the viewing and praising of movies based on how they fare according to her theory of feminism in film, but she still claims that she doesn’t want to be “the sex police”. Director May Hong HaDuong suggests in the film that: “It’s okay to still love and to see a film and say it’s great, but that it has some issues, and I think without questioning it were doing a disservice to our humanity”.

A potential shortcoming of Brainwashed is a lack of credit given to modern films that have flipped the script and used cinematography to challenge the historic sexist phenomena Menkes speaks about. Of all the films featured, the ones Menkes lets off the hook are those that she herself has directed, and this self-promotion does a disservice to her fellow feminist creators who have done similarly disruptive work.

Furthermore, Menkes’ critical theory is equally reductive. Her analysis is based almost exclusively on the interpretation of single scenes, limiting the usefulness of her theoretical framework. This inflexibility simplifies the narrative she pushes but doesn’t account for competing theories such as the phenomenon of the abject, coined in the 1980 essay The Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection by the philosopher Julia Kristeva.

The abject refers to content that induces shock or horror in a viewer by breaking symbolic order or blurring the line between subject and object. Such theories complicate our understanding of how viewers interpret a misogynistic scene, allowing for cases when the problematic nature of a scene becomes a source of empathy for a female character rather than inviting complicity with a male perspective.

Rita Hayworth. Production still from Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power. Image: courtesy of Encounters Documentary film festival.

Something Brainwashed does well is illustrate the connection between the visual language of cinema, employment discrimination against women (particularly in the film industry) and an environment of pervasive sexual harassment, abuse and assault. It’s described as “a circle of violence in Hollywood” in that it takes in what’s toxic in our society, feeds it back to us as a “mirror” but in doing so, re-energises it, perpetuating rape culture and misogynistic tropes.

There is a large focus on the abuse involved in the making of films as well, in the form of disturbing anecdotal accounts from female professionals and an examination of the static statistics of female participation in the film industry.

Director and activist Maria Giese points out that: “People are really happy for women to be attending film schools 50-50 at parity with men, as long as they’re paying money into the system, but when we move into the professional playing field and we’re asking the industry to pay money out to women, that’s where the doors get closed.”

For those who have engaged with feminist film theory before, Brainwashed may seem reductive and possibly even outdated in some ways, considering that its primary theoretical base comes from the 1970s, but the well-edited presentation of basic concepts, with ample examples, should still prove valuable and entertaining. For those who have not, it is far more likely to be a thrilling (if not disturbing) experience, and you may never watch a film the same way again. DM/ML

Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power is currently available in South Africa at select screenings through the Encounters South African International Documentary Festival. Official website. Labia: 28 June, Bioscope: 29 June.

You can contact This Weekend We’re Watching via [email protected]

In case you missed it, also read ‘Navalny’ – the tragic and inspiring story of a man who stood up to Putin

‘Navalny’ – the tragic and inspiring story of a man who stood up to Putin

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.