We're watching

‘Navalny’ – the tragic and inspiring story of a man who stood up to Putin

Daniel Roher’s CNN documentary of Alexei Navalny’s opposition to Russian President Vladimir Putin and the attempt on his life is a tragic and inspiring display of bravery with the terrifying intrigue of a spy thriller. On 12 January 2023, the film won the Oscar for best documentary feature.

The plight of those who oppose authoritarian rule is that, without international intervention, their weapons of choice – logic, evidence and protest – can so seldom overcome brute force and misinformation. Disruptors hope that incontrovertibly exposing corruption will topple a regime, but often it merely provokes suppressive retaliation and at best, international sympathy.

That political martyrs like Alexei Navalny are still willing to lead resistance movements against oppressive autocrats such as Vladimir Putin is an astonishing mark of courage.

Navalny picks up the story of the ex-opposition leader’s campaign against Putin’s Machiavellian, Borgian rule from shortly before Federal Security Service (FSB) agents attempted to assassinate him, but the interviews only began once Navalny had recovered.

The film begins with a short interview exchange that immediately sums up Navalny’s casual charisma and defensive confidence in the face of severe danger. Canadian film director Daniel Roher asks him what message he wants to leave the Russian people if he is killed. Navalny laughs, not because he isn’t worried, but because he hasn’t given up, and laughing is what it takes not to cry.

“Come on Daniel, no way – it’s like you are making a movie in the case of my death. I am ready to answer your question, but let it be another movie – movie number two. Let’s make a thriller out of this movie and if I am killed, let’s make a boring movie of memory.”

Navalny is still alive and the film is the farthest thing from boring, but Roher does give us his answer at its end, sending a clear message about the events that have transpired since these interviews that have seen Navalny thrown in jail, which he may never leave.

Navalny poster. Image: courtesy of Encounters South African International Documentary Festival

Before his imprisonment, Navalny represented by far the greatest domestic political threat to Putin. He has a number of qualities of the “political strongman” which many populist leaders have used to market themselves over recent years. He’s confident, projects strength, always has something witty to say, and it doesn’t hurt that he’s good-looking and 23-odd years younger than Putin.

Roher’s footage of Navalny and his family is intimate and casual. He comes across as vibrant, friendly and passionate. Roher is never lacking in material: footage of protests, arrests, and even the assassination attempt itself are seamlessly integrated so that there’s never an empty moment.

Along with all the deserved flattery, Roher also confronts Navalny about the criticisms he has often faced about having flirted with the radical right-wing earlier in his political career. Navalny is surprisingly bold in saying that he is comfortable sharing the stage with neo-Nazis, basically taking a hard stance that he cannot afford to turn away support and is willing to make coalitions with scum if that’s what it takes to usurp Putin’s tyranny. Charitable supporters would chalk it up to pragmatism, while sceptics would surely be unsatisfied by his vague answer.

It makes no difference to the Kremlin of course, because to them a liberal is already worse than a Nazi anyway. Recognising the threat that Navalny posed, they had him banned from television, radio, rallies – everything they could. Indeed, his support base was so intimidating that Putin refused to refer to him by name – as if he were Voldemort – instead, using farcically wordy titles like “the character in Berlin whom you have just mentioned”.

These prohibitions and avoidant methods of suppression vindicated his resistance in the eyes of the Russian public and evidently were not enough to silence him. Navalny was able to rally support with nothing but a small team and strategic use of the internet, capitalising particularly on young people’s engagement with YouTube and social media platforms like TikTok.

Navalny welcomed the flashing cameras and phones that swarmed his every move – as claustrophobic and overwhelming as it appears, he saw them as a shield. He believed that as he acquired more fame, it would be more problematic to kill him, so he would become safer. Instead, it just made him more threatening – a bigger target.

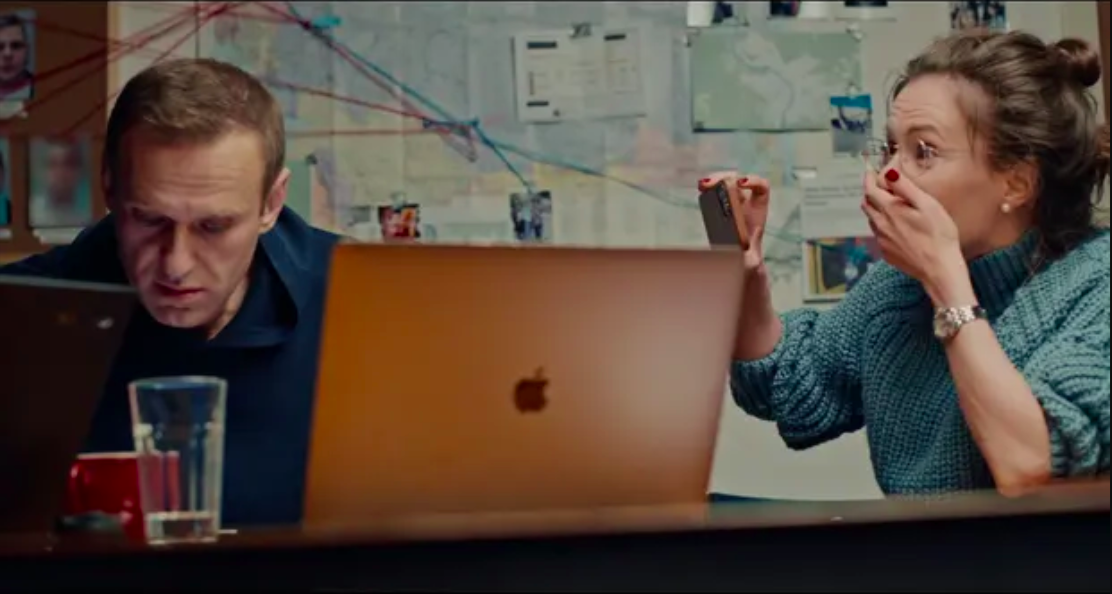

Production still from Navalny. Image: courtesy of Encounters South African International Documentary Festival

The poisoning of Navalny during a flight from Tomsk, Siberia, to Moscow on 20 August 2020 is the core around which the film is built. Knowing that he survived is not enough to ease the tension of this part of the film, edited with empathy in a way that positions the viewer at the scene, in the moment.

Watching the kleptocracy-controlled spin doctors’ (the worst of whom is literally a doctor) flailing attempts to cover up the botched assassination would be funny if they weren’t so blindingly infuriating. A doctor suggests Navalny spontaneously developed a metabolic disorder that lowers his blood sugar, a Kremlin puppet news broadcaster spreads a rumour that he overdosed on moonshine or hallucinatory drugs, and a talk show even blamed his condition on the “endless homosexuality of liberals”.

After two days, Navalny’s family was allowed to take him from the state-controlled hospital to a medical facility in Berlin, but it was thought it would be pointless to investigate the attack since it happened on Russian soil – nobody would share CCTV footage and government agencies would block the inquiry at every junction.

But, astonishingly, the poison that was used was a nerve agent known as Novichok which Leonid Volkov, Navalny’s chief of staff, describes as Putin’s signature poison – the same toxin which had been used before in the attempt to assassinate Sergei Skripal, a former Russian military officer and double agent for the British intelligence agencies.

The documentary imparts a sense of the sheer stupidity of the Russian oligarchy and never is that clearer than when Navalny’s team speak about the decision to use Novichok. Navalny’s first words upon hearing about the poison were apparently: “What the fuck?! That is so stupid.” He was dumbfounded by the idiocy of the attempt. “If you want to kill someone, [publicly] just shoot them.”

Sensing the sloppiness of the operation, Christo Grozev, a Bulgarian journalist from the Netherlands-based online investigative journalism group Bellingcat, begins using Russian back-channels to look into it. He walks you through the fascinatingly innovative yet simple online process he took to track down the manufacturers and players in the poisoning.

Watching Navalny aid Grozev in the investigation of his own attempted murder is utterly surreal, culminating in the flabbergasting highlight scene in which Navalny “prank-calls” a suspect and uncovers crucial information about the Kremlin’s assassination network.

Production still from Navalny. Image: courtesy of Encounters South African International Documentary Festival

The tragedy is that no amount of evidence was going to be enough to save Navalny – if anything, every action he took to expose Putin’s crimes brought him closer to imprisonment or death. The film ends with his greatest act of defiance – returning to Russia after the attempt on his life. In the past few days, at the time of publication, he has been moved to a maximum security prison and had years slapped onto his sentence… nails in the coffin.

Navalny is inspiring, enthralling and devastating. One knows going into it that there is no happy ending, and maybe the message to take out of it is that there never can be until there is international intervention. DM/ ML

This story was first published on 17 June 2022.

Navalny is available in South Africa at select screenings through the Encounters South African International Documentary Festival Official Website: Labia: 24 June, Bioscope: 25 June, Cinecenter Kilarnay Mall: 1 July.

You can contact This Weekend We’re Watching via [email protected]

In case you missed it, also read Welcome to the wheel world – Richard Hammond’s new TV show was a harsh reality check

Welcome to the wheel world – Richard Hammond’s new TV show was a harsh reality check

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

This man is an inspiration considering the people that are now leading most of the world.