OP-ED

Reflections of a Wayward Boy: The bitter battle to free Moses Mayekiso

Our final nearly nine-year exile in London included involvement in the lost battles of the last great miners’ strike and the fight at Rupert Murdoch’s digitised Wapping plant. But the bitter learning experience was in initiating and coordinating what was probably the biggest trade union-based anti-apartheid campaign, the Friends of Moses Mayekiso.

When Barbara and I launched the Friends of Moses Mayekiso (FMM) campaign in 1986, we expected that we would face some animosity from the SA Communist Party (SACP) – dominated by the “official” Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM) and the ANC in London.

They had ignored the detention of one of South Africa’s leading trade unionists and continued to demand that all anti-apartheid activity be “officially” approved by them. The ANC-aligned and self-exiled SA Congress of Trade Unions (Sactu) also still claimed to be “the only true representative of South Africa’s workers”, something the emerging South African unions refuted.

However, we thought that this exile cabal had learnt a hard lesson two years earlier when David Kitson, one of the longest serving white political prisoners in South Africa, was released after serving nearly 20 years. His wife, Norma and children had launched an officially unapproved non-stop picket outside South Africa House in London, organised by the City Anti-Apartheid group (City AA), demanding the release of David and all political prisoners.

Although harassed by the police and reviled by the “official” movement, this picket lasted and became after years of demonstrating day and night in all weathers, an icon of anti-apartheid solidarity. Pop groups, including UB40, performed on those pavements where MPs and men and women in city suits often stood shoulder-to-shoulder with punks in tattered jeans, sporting multi-coloured Mohican haircuts.

In a rather meaningless gesture, because no authority existed, the AAM executive announced that City AA was expelled. We, through our local group and along with about a third of the groups nationally affiliated to the official AAM, continued to support City AA and the picket.

Then, in May 1984, Kitson, an SACP member, was finally released and arrived in London where he was instructed by his party to denounce his wife and call for an end to the picket. He refused – and was expelled from the SACP. He was also suspended from the ANC which he had never joined since he had gone to prison before non-black South Africans could be ANC members.

Worse was to come: he lost a “job for life” at Oxford’s Ruskin College that was promised – and funded – by the engineering union, Tass, headed by British Communist Party member Ken Gill. Kitson proved a great success among students and staff at Ruskin but, in less than six months, after refusing to condemn his wife’s actions and the picket, Gill withdrew the funding. The outcry was fierce and at least ensured that there were never again such expulsions.

However, the attacks we faced were also nasty – and at a level we never expected. Not only because of the backlash over the Kitson affair, but also because we thought our FMM campaign would not be much more than a cottage industry of protest involving ourselves, our children, a few friends and the local Greenwich and Bexley AA group.

But within weeks, it was obvious we were in danger of being overwhelmed. Demands for protest postcards that we had printed and offers of help poured in along with money; petitions were being drawn up and protest letters written. Unions from as far afield as Brazil and Japan made contact, along with the mighty automotive workers’ union in the United States. We could clearly continue to act as a “switchboard” and coordinate with the South African unions and the International Metalworkers’ Federation (IMF), but we needed help.

When I explained the situation to National Union of Journalists general secretary Harry Conroy and his deputy, Jake Ecclestone, they agreed that the NUJ would house the campaign. They also seconded an administrator, Joan Amory who, with the aid of volunteer assistants, handled the mail, the receipting and banking. A former Labour Party MP, Ernie Roberts, agreed to act as treasurer. At that stage, Mawu/Numsa had also asked for funding to assist the sacked strikers at BTR-Sarmcol, near Howick.

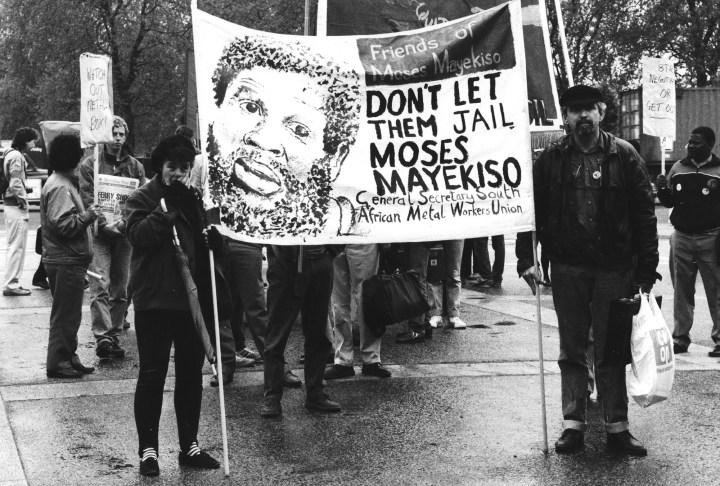

Terry Bell picketing for the release of SA Metalworkers’ Union General Secretary Moses Mayekiso. (Photo: Supplied)

There were volunteers galore, many from the Socialist Workers’ Party (SWP) who agreed with us that the FMM should be a single-issue campaign, whereas some groups saw it as a vehicle on which to build a “non-sectarian AAM”. The largest of the revolutionary Left parties, with an excellent industrial organiser, Sheila McGregor, the SWP argued that countries such as the Soviet Union were not socialist, but state capitalist. I agreed and eventually joined the SWP which was later to expel me.

By then, I was co-editing the Africa Analysis newsletter which gave me access to an office and, with the support of publisher Richard Hall, the use of what were then the latest Apple computers. The internet had yet to dawn, but we were able to use the technology not only to design and print artwork for a series of newsletters, but also, using an acoustic coupler, to receive reports when the trial of what became known as the “Alex 5” began in September 1987. These were sent via call boxes in South Africa by volunteer journalists.

With the death sentence an initial possibility, it seemed imperative that something more dramatic be done to build support. The idea of a full-page advertisement in the liberal The Guardian newspaper immediately gained the backing of five trade union general secretaries, a host of Labour Party MPs and of fellow exile Lionel Morrison, president of the NUJ, who had been the youngest accused in the marathon 1956 treason trial in South Africa.

But as even more support poured in from further afield, Zola Zembe (Archie Sibeko) the Sactu coordinator, issued a public attack demanding that “there should be no support for, nor affiliation to” the FMM. We ignored this and, although it created a few problems, it flopped. There was such support for the ads that we were able to run a full page in The Independent newspaper as well. Christmas and May Day greetings advertisements were also placed in South Africa’s anti-apartheid press.

By November 1987 we had already been able to report that the campaign had “produced 35,000 photocopiable factsheets, 22,000 postcards, 20,000 badges, 20,000 stickers, 17,000 posters and more than 40,000 A4 leaflets”. Nearly £3,000 worth of silk-screened T-shirts had also been bought from the co-operative set up by BTR-Sarmcol strikers.

Six leading British graphic artists, members of the informal 032 Group, also produced sets of specially designed FMM greetings cards, two of which were banned by the apartheid authorities. Anti-apartheid members of the actors’ Equity Union, as “Performers Against Racism” then decided that a benefit concert would be a great way of showing support and raising funds. The 1,200-seat Hackney Empire was booked along with major acts, headlined by comedian Ben Elton.

Numsa, Cosatu and the “Alex 5”, along with Herman Rebhan, general secretary of the International Metalworkers’ Federation, “representing 14 million affiliated metalworkers”, together with Moses Mayekiso’s wife, Kola and the United Autoworkers of the USA sent solidarity greetings. And these were needed. Because, on the night of the sold-out event, in an apparent last-ditch attempt to sabotage the show, Ben Elton and several of the performers were contacted and told to withdraw as the benefit was not approved “by the South African unions or the AAM”. But we had the evidence and the show went on, raising £8,000 (then R31,000) for the Numsa relief fund.

Kola Mayekiso then came to England and we embarked on a two-week trip around the country addressing up to five shopfloor, union and AAM group meetings a day, culminating in a packed gathering in the Trades Union Congress auditorium in London. Change was clearly on the way in South Africa and it would also not be long before the Alex 5 were released. When they were, there was one last – and spontaneous – celebration attended by a jubilant TUC general secretary, Norman Willis.

Life then settled down to a less frenetic pace until 11 February 1990 when I heard officially that I was no longer a banned person. I decided to go home. “Not so fast. First check at the embassy if you need a visa,” said Barbara. I did, and was told – eventually and after some protest – that I could return, but should remain “in the magisterial district of Johannesburg and not engage in any journalistic activity”.

These were details I could obviously ignore, so I booked my ticket and my colleagues at Africa Analysis organised a farewell party on the same afternoon that a major demonstration was called to oppose the visit to London by the French ultra-right leader, Jean-Marie Le Pen. He was staying at the Charing Cross Hotel alongside Charing Cross railway station, on my route home.

When I got to the station, commuters had to walk between ranks of police to the single entrance left open. I couldn’t resist the temptation: I loudly addressed other commuters about the fact that the police were protecting a fascist. They were being treated by their bosses like zombies and this had been the case ever since the police strikes of 1918 and 1919. Following those strikes, trade unionism had been banned for the police force. I had barely got into my stride before the biggest policeman I have ever seen grabbed me by the collar and hoisted me into the back of a police van.

The only consolation, after I had been searched and locked up, was that I had finally got to see the inside of the famous Bow Street police station. Released in the early hours of the next morning I soon realised the police had discovered that I was scheduled to fly to South Africa in a matter of days: they had booked my day in court for the following week.

“Never mind,” said the long-suffering radical attorney, Jim Nichol. “You don’t personally have to be in court.” So I flew to Johannesburg, Nichol appeared on my behalf and the case was thrown out. At last, after 27 years of exile, I was home. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.