SCORPIO

Shayne’s World: How R1.8bn in UIF cash vanished in Coast2Coast debt hole

How does one lose nearly R2bn in public money? One way, it seems, is to invest it in a business with loads of debt buried beneath an insanely complex corporate structure. We unpack how the Unemployment Insurance Fund, and others, got burnt in the Bounty Brands debacle.

On paper, the case for investing public monies in a group like Bounty Brands might have seemed solid.

First, there was the ever-growing basket of well-known consumer brands in Bounty’s stable. Think Diesel, Hurley, Vans, Haägen-Dazs ice cream and Tuffy homeware products, among many others.

Add to this the prospect of an international footprint, driven through acquisitions of consumer goods businesses in Europe. And, finally, there was the promised dual listing on the Johannesburg and London stock exchanges, which could have unlocked great value for the group’s shareholders.

But the listings never happened, and Bounty Brands has come close to total ruin.

Instead of holding a valuable stake in a promising business, the UIF has effectively lost R1.8-billion.

Other victims in this debacle are a host of individuals and businesses who all lost a heap of money. This includes the owners of some of the vendor businesses that had been bought by Bounty Brands. Several Bounty Brands executives and employees held shares in the business and also suffered losses.

Many of those familiar with the saga blame businessman Gary Shayne and his private equity firm, Coast2Coast Capital, for the costly mess.

Gary Shayne, Coast2Coast Capital’s CEO. (Photo: Supplied)

As the equity firm behind Bounty Brands, Coast2Coast was responsible for securing the financing necessary for growing the group. Somewhere in the process, Coast2Coast ran into trouble, and it started defaulting on some of its debts.

Had it not been for these defaults, the UIF’s investment would possibly still be safe.

But Shayne denies that he or Coast2Coast Capital are responsible for the fiasco. According to Shayne, the blame lies with the management team Coast2Coast appointed to run Bounty Brands.

The parties involved in the affair have offered various alleged causes and counter-allegations as to the reasons for the Bounty crisis.

We’ve packaged their responses in this article.

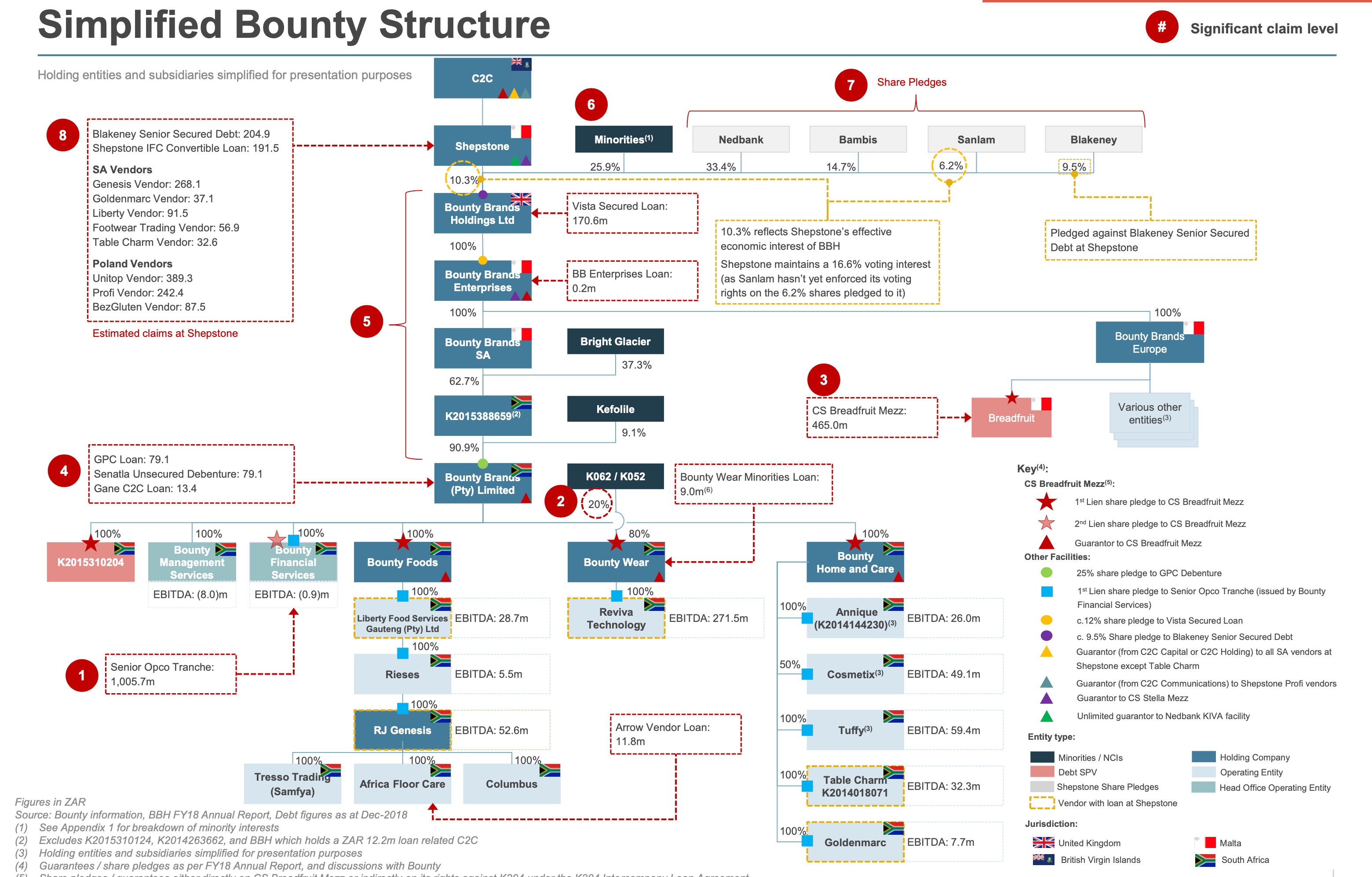

To understand how the UIF and others lost their money, we need to look at Bounty Brands’ origins and its relationship with Coast2Coast. We also need to unpack the convoluted corporate structure that tied the groups together.

Want the short version? Read how the UIF lost R1.8 billion – in a nutshell

This investigation is buttressed by documents filed in ongoing court proceedings, additional records provided to Scorpio, and information sourced during interviews with several individuals familiar with developments at Bounty Brands.

Genesis

Bounty Brands was founded by Shayne’s Coast2Coast Capital in 2014.

This was about a year after Coast2Coast had listed another of its creations, Ascendis Health, on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE). Ascendis, essentially a holding company for a basket of health and wellness businesses, scored a considerable equity injection in 2016.

The boon came via businessman Lawrence Mulaudzi, one of the key roleplayers in alleged malfeasance involving deals with the Public Investment Corporation (PIC).

As the UIF’s investment manager, the PIC invested R1.4-billion of UIF cash in Mulaudzi’s company, Kefolile Health Investment Holdings. Kefolile subsequently bought a stake in Ascendis, giving the UIF an indirect share in Coast2Coast’s JSE-listed health group.

This investment turned out to be the PIC and the UIF’s first folly involving Mulaudzi and one of Shayne’s creations. Shortly after the investment, the Ascendis share price started to plummet.

From a peak of more than R28 per share, the Ascendis share price has fallen to below R1, meaning the UIF’s investment has largely been wiped out.

Below is Shayne’s full account of the reasons behind the Ascendis collapse.

Chris Dillon (left) and Dr Karsten Wellner (middle) with Gary Shayne during the listing of Ascendis Health on the JSE in 2013. Dillon was Shayne’s partner in Coast2Coast, and Wellner was Ascendis Health’s CEO. Through investments in Ascendis and Bounty Brands, the UIF has lost more than R3-billion. (Photo: Supplied)

Bounty Brands, meanwhile, was established on much the same principle as Ascendis.

The idea was to acquire a wide range of businesses in the consumer goods sector, bundle them together in a holding company and then list the holding company on the stock exchanges.

If this approach sounds familiar, it might be because it is very similar to the Steinhoff playbook.

In fact, Bounty Brands’ principals were the first to liken their group’s “aggressive buy-and-build strategy” to the one implemented by Markus Jooste’s infamous conglomerate.

One trait of this model is that it generates high levels of debt, mostly driven by acquisitions.

In its first year, Bounty spent about R500-million on the first collection of businesses it bought. This included Chappers Sports Direct, the South African distributor of VANS footwear and clothing.

The acquisitions drive continued in 2015 and 2016, when Bounty Brands parted with more than R700-million for new acquisitions. It bought RJ Genesis, a distributor of homeware and cleaning products, and Musgrave, the local distributor of Jeep clothing, among others.

By 2017, Bounty Brands held 12 businesses, or vendors, in its South African portfolio. It had also begun buying companies in Poland.

The debt that arose from these acquisitions took on several forms:

First, the owners of some of the businesses Bounty bought weren’t compensated in full at the point of sale. They received only a portion of the monies owed to them. The outstanding amounts for these acquisitions were taken up in the broader Bounty group’s balance sheets as “deferred vendor liabilities”.

In other words, Bounty undertook to repay these vendors somewhere down the line.

To be more precise, obligations to these vendor businesses sat with one of the entities in Shayne’s Coast2Coast group. We’ll unpack this dynamic in more detail further on.

By March 2019, these “vendor obligations” had risen to roughly R500-million, according to one of the documents we have obtained.

“We sold our businesses to Bounty, and the group was earning revenues from our companies, but we were never settled in full,” lamented one owner of a company Bounty bought.

Like other vendors we have spoken to, this person asked to remain anonymous.

R3.4-bn debt pile

Bounty Brands’ debt also consisted of much larger liabilities than the monies owed to the vendor businesses.

To fund its acquisitions and cover other costs, the Bounty group naturally had to raise funding and obtain hefty loans.

As the private equity business that had founded Bounty, this responsibility fell to Shayne’s Coast2Coast.

This is where the PIC and the UIF, along with a host of other lenders and investors, fit into the picture.

In 2016, the same year in which the PIC channelled UIF monies to Ascendis Health via Lawrence Mulaudzi, another of Mulaudzi’s companies obtained a 9% stake in Bounty Brands (Pty) Ltd.

The latter entity had been established to house the South African consumer goods businesses in the group’s stable.

As with the Ascendis transaction, this deal was facilitated by the PIC, which had made R406-million in UIF funds available to Mulaudzi’s company to bankroll the investment.

Another UIF deal followed in 2018, again involving Mulaudzi and the PIC.

This time, the PIC injected nearly R1.4-billion of the UIF’s cash into a company called Bright Glacier Trading.

Bright Glacier used the funds to buy a 36% stake in Bounty Brands’ direct holding company, K2015388659. We’ll refer to the latter entity simply as K659.

The Bright Glacier deal saw one of Mulaudzi’s companies pocket a R50-million transaction fee.

As we previously revealed, nearly R6-million of this fee was seemingly channelled to a property deal that benefited then ANC treasurer-general Zweli Mkhize’s family trust.

Exposed: Zweli Mkhize’s R6m ‘cut’ from PIC’s R1.4bn deal using Unemployment Insurance Fund money

Bounty Brands’ top executives, CEO Stefan Rabe and CFO Peter Spinks, emphasise they were in no way involved in Coast2Coast’s negotiations with Mulaudzi.

“The first time I met Lawrence Mulaudzi was in the room on the day we signed the [investment] documents,” Spinks told us in a recent interview at Bounty Brands’ Cape Town offices.

Shayne has also denied any knowledge of an alleged kickback.

“No, I was not aware of it and I do not know anyone who was aware of it. The first time I became aware of it was when I read the press article,” he states.

Businessman and PIC dealmaker Lawrence Mulaudzi. (Photo: Supplied)

Meanwhile, the wider Bounty group, which included Coast2Coast entities, also secured loans and other forms of funding from a range of large banking groups and financiers, including Nedbank, Absa, Sanlam and Credit Suisse.

It also relied on funding from smaller investment outfits and private investors.

In due course, the Bounty group’s debt stood at a hefty R3.4-billion, according to a document in our possession.

This was made up of all manner of debt instruments, including loans, debenture subscriptions and mezzanine finance, along with the outstanding payments owed to the businesses Bounty had acquired.

These liabilities were held within a variety of entities that formed part of the expansive corporate structure that is Bounty Brands.

The web of Bounty Brands and Coast2Coast entities, described as “highly complex” in some group documents, consisted of companies registered in South Africa and in foreign jurisdictions like Malta, the British Virgin Islands and the UK.

Entities in Shayne’s Coast2Coast group were plugged into the string of Bounty Brands businesses.

In fact, through this complex structure, Shayne’s Coast2Coast was effectively the majority shareholder in Bounty Brands.

Shepstone Capital, one of Shayne’s entities registered in Malta, owned most of the shares in Bounty Brands UK, the business that was going to be listed on the Johannesburg and London bourses.

The group’s debt arrangements were as complex as its corporate structure.

This is the ‘simplified’ rendering of the wider Bounty Brands corporate structure, which included entities in Gary Shayne’s Coast2Coast group.

Some senior loan facilities from the likes of Nedbank and Absa were housed in a South African entity called Bounty Brands Financial Services.

Further afield, the Bounty group had incurred big debts that were held in some of the offshore structures.

For instance, Breadfruit Holdings, a special purpose vehicle (SPV) registered in Malta, sat with a R465-million loan from Credit Suisse.

This loan had been used for the acquisition of consumer goods businesses in Poland.

Another Credit Suisse loan of about R170-million was held within Stella Pack, another Polish business Bounty had bought in 2017.

Yet more of the group’s debt sat with Shayne’s Shepstone Capital, including the deferred liabilities for the businesses Bounty had acquired.

This Byzantine structure of interlinked entities and related debts is a lot to process.

But the key takeaway is this: The Bounty group, a collection of local and foreign entities partly made up of structures in Shayne’s Coast2Coast group, generated a hefty pile of debt during its acquisitions drive circa 2014 to 2018.

Some of these debts, although located in offshore entities, were structured in a way that had far-reaching implications for Bounty’s South African shareholders and creditors, including those financed by the UIF.

This is because shares in the group’s valuable operating entities had been pledged as security for these loans.

Read in Daily Maverick: UIF’s R1.8bn loss: Here’s how it happened – in a nutshell

If, for instance, Bounty defaulted on the Breadfruit SPV’s loan from Credit Suisse, Credit Suisse could have laid claim to stakes in some of the businesses in Bounty’s South African portfolio.

This would have had an adverse impact on the value of the stakes in the group that were held by the likes of Kefolile Consumer Brands and Bright Glacier Trading.

Were this to happen, the UIF, as a shareholder in Kefolile and Bright Glacier, would also have taken a knock.

In the end, the Bounty group’s mountain of local and foreign debt indeed came crashing down.

It sparked a crisis that saw the UIF’s R1.8-billion investments effectively rendered worthless.

The R100-million ‘oversight’

“I am concerned about these issues that crop up out of the blue. This was never disclosed to us as the board,” wrote Dr Moretlo Molefi, Bright Glacier Trading’s managing director, in an October 2018 email to Spinks.

This was only five months after Bright Glacier had pumped nearly R1.4-billion in UIF funds into Bounty Brands, and already there was trouble on the horizon.

Bright Glacier’s stake in the group was held in K659, the holding company for Bounty Brands (Pty) Ltd.

Molefi sent the email in her capacity as a board member of K659.

Her frustration stemmed from a R100-million liability that had suddenly fallen into K659’s lap.

In 2015, a South African entity called Ganefin6 — one of the myriad structures in Shayne’s Coast2Coast universe — had obtained a R100-million loan from Greenpoint Capital, a private investment firm headquartered in Cape Town.

The loan was due to be repaid in August 2018, but Ganefin6 didn’t have the money to pay.

This was a problem for Molefi and Bright Glacier, for the following reason:

At some point after Ganefin6 secured the loan, Coast2Coast pledged 25% of K659’s shares in Bounty Brands (Pty) Ltd to Greenpoint Capital as security.

Seeing as the penniless Ganefin6 had now defaulted on the loan, Greenpoint Capital was within its rights to perfect the guarantee, meaning it could gobble up a quarter of Bounty Brands’ shares.

Bounty Brands, of course, housed all of the group’s valuable South African operating entities.

Were Greenpoint to have perfected its guarantee, it would have severely diluted K659’s stake in Bounty Brands. As a shareholder in K659, Bright Glacier, along with the UIF, would have taken a knock.

In another email to Spinks and Rabe, Bright Glacier claimed it had been kept in the dark about this crucial matter.

The 25% share pledge was a “material liability”, one that had not been “disclosed in full” to Bright Glacier before it invested the UIF’s money in Bounty Brands, complained Rachel Mphephu, Molefi’s partner.

In a replying email, Spinks said the matter had been disclosed in K659’s annual financial statements and that these had been provided to Bright Glacier at the time of the UIF deal.

However, Rabe seemingly conceded that Bright Glacier may have had a point.

“I accept that the share pledge and guarantee could have been more clearly defined in the agreements,” said the Bounty CEO in another email in this chain of exchanges.

This had been “merely an oversight”, he had added.

Bright Glacier Trading’s managing director, Dr Moretlo Molefi. (Photo: Supplied)

The emails were filed in an ongoing court spat involving Bright Glacier, Kefolile and Bounty Brands.

Molefi and Mphephu may have had good reason for feeling aggrieved, but it appears as if Rabe and Spinks themselves were equally blindsided by Coast2Coast’s default.

By this point in time, there was palpable tension between Bounty Brands’ executives and Shayne’s Coast2Coast, judging by the emails.

“The reality is that none of us work for C2C [Coast2Coast], and unfortunately we are not kept informed by C2C of its circumstances at all times and often only become aware of events as they impact us,” Spinks told Molefi and Mphephu in one email.

Spinks added that the Greenpoint Capital default had caused them “enormous frustration”.

This issue was ultimately resolved by moving the R100-million Greenpoint Capital liability onto K659’s books, instead of having Greenpoint take up the 25% stake in Bounty Brands (Pty) Ltd.

As part of this arrangement, Greenpoint Capital was also set to receive a partial payment of R25-million, which would be funded by the monies Bright Glacier had received from the UIF.

In other words, the UIF’s money was now effectively being used to help mend the damage caused by the Coast2Coast default.

Seeing as this new liability affected K659’s shareholders, Bright Glacier was “made whole” by being given a few extra shares in K659.

Shayne had only this to say about the default: “The Greenpoint Capital loan was dealt with and essentially refinanced.”

That may have been true, but the group’s wider problems were far from over.

Debt doom

As things turned out, the default on the Greenpoint Capital loan was merely a harbinger of the Bounty group’s real woes.

Starting in around October 2018, entities in Shayne’s Coast2Coast group also began defaulting on obligations to other creditors, including to vendors who had sold their businesses to Bounty Brands.

These defaults were like sparks to a pyre.

Because of cross default provisions, some of the group’s other loan facilities were immediately in default too, explained Spinks.

The initial defaults also set off “a cascade of security enforcements”.

Creditors who were owed money could lay claim to certain shares that had been put up as security for the loans.

Shepstone, for instance, had pledged its shares in Bounty Brands UK as security for some of its debt.

When Shepstone defaulted on these debts, creditors took up their beneficial rights to the shares Shepstone owned in Bounty Brands UK.

This brought about a change of control at Bounty Brands UK, which, in accordance with the provisions of certain loan facilities, accelerated the maturity dates for those debts.

This is a lot to take in, but what it boils down to is this:

The entities in both the Bounty Brands and Coast2Coast groups were intimately related to one another, and so were the debts spread across this vast network of businesses.

Because of Coast2Coast’s initial defaults, a snowball of accelerated claims from other creditors came hurtling towards Bounty Brands.

“The effect of all of this was that the aggregate amount called up for repayment over the period October 2018 to April 2019 was approximately R923-million,” explained Spinks and Rabe in a written response.

In other words, the Bounty group suddenly needed to find nearly R1-billion to placate its creditors, or it risked going under by way of liquidation.

This figure included the monies owed to Credit Suisse.

These events in late 2018 hit Bounty Brands like a sucker punch to the gut.

“You go from this world where there is no pressure on your balance sheet to immediate pressure,” Spinks told us.

Peter Spinks, CFO of Bounty Brands. (Photo: LinkedIn)

One way in which the group would have been able to generate enough funds to avoid its debt-driven demise was through its intended dual listing on the London and Johannesburg stock exchanges.

Unfortunately, this was no longer an option, mainly due to the defaults on the Coast2Coast entities’ debts, explained Rabe and Spinks.

“To the best of our knowledge, the decision to abandon the planned listing was taken by C2C in or about November 2018,” they told us.

Shayne has identified the non-listing as “probably the biggest factor” leading to the Coast2Coast defaults.

“As an investment holding company, Coast2Coast’s primary means of funding was either dividends or the sale of equity,” said Shayne in a written response.

He added: “The liquidity event being the sale of Bounty Brands equity via its planned listing was delayed and before that could take place Bounty’s lenders prevented any dividends flowing to its shareholders including Coast2Coast causing a funding squeeze.”

Shayne blames Bounty’s management for the aborted listing, but Rabe and Spinks have strongly rejected his assertions. Click here for a fuller account from each of the two parties.

One former Coast2Coast insider said the group may have taken way too big a gamble with the planned listing.

“Everything was riding on the listing being successful,” said the source.

“The build-and-list play only works until it stops working. It was all debt, the business model was always going to collapse, if you ask me,” the former Coast2Coast employee added.

Facing possible liquidation, and with the intended listings no longer an option, the Bounty group was in desperate need of a solution.

Rabe and Spinks make no secret of the fact that they blame Coast2Coast for the calamitous defaults.

“I wouldn’t say we’re friends,” Spinks wryly joked during our interview.

“There is very little to no contact [between Bounty Brands and Coast2Coast]. We parted in an extremely bad way,” added Rabe.

Restructured

To save the group, Bounty Brands started looking at options for restructuring the group’s near-fatal debt.

This gained momentum in around March 2019.

The restructuring would be done without Coast2Coast, which had effectively “disappeared” after the defaults, according to Rabe.

Bounty Brands could try to find new lenders or investors, or it could borrow even more money from existing creditors.

Several options for a possible restructuring were tabled throughout 2019 and 2020.

Meanwhile, from March 2020, Covid-19 had also become a factor. Because of lockdowns and dire economic conditions during the pandemic, the group’s apparel and other businesses weren’t doing as well as before.

This made it doubly difficult to entice investors to risk putting even more money into the ailing group.

In December 2020, Bounty Brands’ executives finally approved and implemented a restructuring plan called Project Victoria, also known as the second alternative deal.

This restructuring would have severe consequences for pretty much anyone with a financial stake in the group.

At the time of the debt defaults, Coast2Coast’s Shepstone Capital owed the South African vendor businesses roughly R500-million altogether. This was on top of obligations to some of the foreign businesses the group had bought.

Through the restructuring, the owners of these businesses received only a portion of the monies owed to them.

The remaining debt to the South African vendors totalled roughly R300-million. This was converted into equity in Bounty Brands.

Several of these vendors are far from happy with this arrangement.

“The shares are worthless,” claimed one owner of a vendor business sold to Bounty.

Rabe and Spinks aren’t unsympathetic to the vendors’ plight. But they still believe the restructuring was the only way in which Bounty Brands could be saved.

“Every single shareholder, bar none, lost their value in that whole process, us included,” said Rabe.

Coast2Coast also got hurt in the process, Shayne told us.

“It’s important to note that Coast2Coast lost in excess of R3.5-billion in equity value in Bounty as a result of this.”

Mere crumbs

The UIF, of course, is one of the biggest losers.

And it didn’t just lose equity value, but a fortune in public monies.

Thanks to the restructuring, the fund’s R1.8-billion investment has effectively evaporated.

This is because the shares Bright Glacier Trading and Kefolile held in Bounty Brands were severely diluted as a result of the restructuring.

Here’s how it happened:

The restructuring raised more than R900-million in new funding from a suite of new and existing creditors.

In the process, a new entity, Newco, was established to house the group’s valuable vendor businesses.

In exchange for the injection of new funds, the suite of investors received an 80% stake in Newco.

Bounty Brands (Pty) Ltd’s stake in Newco, however, was limited to a measly 20%.

This had grave consequences for both Bright Glacier Trading and Kefolile, who — directly and indirectly — held their stakes in the group through Bounty Brands (Pty) Ltd.

Their combined effective shareholding in the valuable vendor businesses were consequently diluted from 28% to just 5%, according to Molefi’s court filings.

As a shareholder in Bright Glacier and Kefolile, the UIF ended up with an even smaller piece of the Bounty pie.

Bright Glacier Trading and Kefolile subsequently launched a legal bid to declare the restructuring unlawful. The applicants allege the solution was forced upon them in a dubious manner.

They claim they, as shareholders in the group, were not afforded an opportunity to vote on the resolution that approved the deal, among other grievances.

Rabe and Spinks won’t comment on the restructuring because of the ongoing court case, which is currently being heard in the Cape Town High Court.

However, in one of his affidavits filed in the matter, Rabe strongly denies Molefi’s allegations.

Bright Glacier and Kefolile were kept well informed of all aspects of the restructuring process and it was ultimately passed in a lawful and transparent manner, Rabe argues.

Even though Bright Glacier and Kefolile have maintained small stakes in the group, it is doubtful whether their investor, the UIF, will ever recover any of its money.

People queue at the Department of Labour in Cape Town in May 2020 to claim money from the Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF). (Photo: Gallo Images / Nardus Engelbrecht)

The UIF, for its part, has apparently made peace with the fact that the entire R1.8-billion investment has gone down the drain.

As we’ve previously reported, the UIF’s R1.37-billion investment in Bright Glacier has been impaired by its own auditors.

And the R406-million investment in Kefolile is now worth less than R3-million, according to the fund’s 2019/20 annual report.

As for Bounty Brands, the 2020 restructuring has apparently returned the group to a “financially stable position”, Rabe states in one of his affidavits.

Nothing is certain, but with improved economic conditions the business may yet yield the bounty its original investors had set their sights on.

But that won’t materially benefit the UIF.

Despite investing a staggering R1.8-billion in the group, the fund’s indirect stakes in Bounty Brands are now so small that any possible returns are sure to be nothing but crumbs. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

What a disaster and more tax payers money stolen and people in need of UIF will suffer. A few questions: Why and how is public used to speculate on the stock market? How did they manage to secure these huge loans? Different rules obviously for people who need a mortgage or a business loan. Is anyone in the bank going to be held responsible? And what does “down the drain ” mean practically? If something is put in the drain it goes somewhere, but where? And lastly, will these crooks be living the high life a year from now or will they be stripped of all they have? This is what happens to ordinary people when they lose their job or their small business.

The biggest mystery is why owners of a business would sell it and allow the income to accrue to the purchaser without being paid in full. The only way that it makes sense, assuming the Seller is half intelligent, is if the part purchase price paid was actually the full value of the business and the deferred sum over and above the true value.

Fraud appears to be South Africa’s GDP!

Here are a whole bunch of people using other people’s money for hare brained money-making swindles. What concerns me most is we dont really know where our financial assets are being deployed, and there is no shortage of greedy dishonest “financial advisers” on the loose in our world!

Its certainly a case study for the old adage “bullshit baffles brains”!

Exactly, there needs to be a full investigation as to where the funds went. It doesn’t sound like there was much business activity, just lots of borrowing.

This is one complicated article! all I would like to know is how did the leaders of this pack compensate themselves and what financial gain have they afforded themselves during the couple of years they ran this “scheme” are they affected as they claim or ………. are they walking away only a little poorer than very rich!

‘Private equity’ is a curse of modern economics. Take a short-term loan. Purchase company. Saddle said company with a huge (balloon) loan which (a) liquidates the short-term loan & (b) pays the partners of the ‘private equity’ entity a dividend. The leveraged company is responsible for- & has to pay off the debt. In addition, the ‘private equity’ entity charges said company monthly ‘management fees’. If all works out, the company is sold & the partners, once again, take a clean profit. Should the company fail, the partners have theirs & can walk away. (Undiscussed is how the PE entities degrade corporations by squeezing value – cutting costs – to maximize cash flow…)