RULES OF THE GAME

Rugby’s quest for mass appeal is compromised by ever-changing laws

Wildly altering law interpretations and different laws in different competitions are frustrating the game’s fanbase.

Confusion is commonplace in the press box nowadays. Every five minutes or so, a colleague will tug at your arm and ask you to explain why a particular penalty or card has been given.

As you consider the laws, or rather how they are being applied in a particular tournament, you ask yourself whether this is good for the game. You look out into the stands and wonder what the fans must be thinking.

The more dedicated among them may be up to speed with the latest law variations. They may know why a particular penalty has been awarded, or why a particular player has been shown a red or yellow card.

Most fans, however, wear expressions of confusion and frustration, as if they don’t understand what is unfolding before them. Without the benefit of an explanation, they remain in the dark.

Simplification over interpretation

Rugby demands so much of its fans nowadays. We’re encouraged to accept that the interpretation of the law-set will vary from referee to referee.

We’re told that referees shouldn’t blow the game to the letter of the law, as that would result in a stop-start contest and the spectacle would die an agonising death.

Often it feels as if our intelligence is being insulted, as if the powers are instructing us to forget about the intricacies of the laws and to just enjoy the show. But rugby is not WWE. It’s not about bringing a few athletes together for entertainment purposes. Every action, decision and result has a consequence.

Games, seasons and careers can swing on specific moments. If rugby wants to grow its fanbase, it needs to ensure that the big moments leave little to interpretation, and that they are clear enough for the casual observer to appreciate.

Indeed, there are many lessons that rugby can take from football, a relatively uncomplicated game that is followed throughout the world. You certainly don’t need to have a PDF of the latest law book at hand when attending a local football derby or when you’re watching the English Premier League on TV.

The current law-set is overly complicated, as many former players, coaches and referees have opined. Officials are encouraged to pick and choose which law to enforce – particularly around the breakdown – and to strike a balance between managing the contest and the spectacle.

The referees are publicly criticised for missing certain transgressions, but later, behind closed doors, they are praised by their bosses for their attempts to keep the game flowing. This is not a critique of referees, but rather a critique of a system built on flawed priorities. Again, you have to wonder whether this system is doing more harm than good in terms of growing the game.

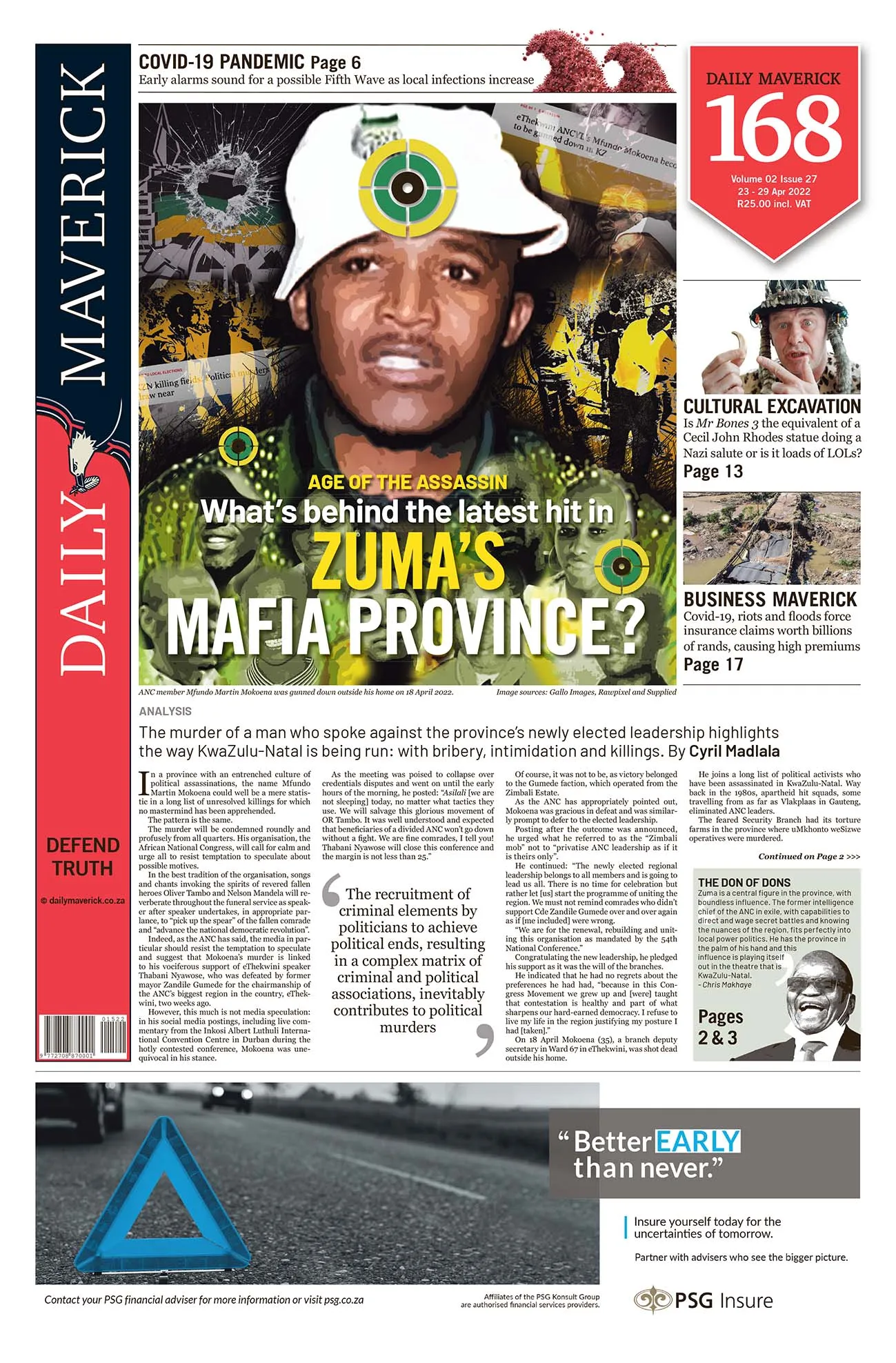

Moment of interest from Bismark du Plessis of the Vodacom Blue Bulls during the United Rugby Championship match between Vodacom Bulls and Munster at Loftus Versfeld on 12 March 2022 in Pretoria, South Africa. (Photo: Gordon Arons / Gallo Images)

Different strokes

Fans are being asked to work even harder when viewing tournaments staged across different regions.

Over the past few weeks, you may have watched the South African franchises in the United Rugby Championship (URC) and Currie Cup, the Australasian and Pacific island teams in the Super Rugby Pacific tournament, the European clubs in the Champions Cup, English Premiership and French Top 14, and the local universities in the Varsity Cup and Varsity Shield finals.

You may have noticed how the laws of the game vary from tournament to tournament.

Competitions such as Super Rugby Pacific allow red-carded players to be replaced after 20 minutes. The same law is in place for the Varsity Shield, whereas the Varsity Cup allows the ejected player to be replaced after 15 minutes.

The 50:22 law was initially implemented in the southern hemisphere competitions, and is now used in tournaments around the world. The Varsity Cup is trialling a new variation of this law that prescribes a quick tap instead of a line-out for the attacking team. The Varsity Shield, however, doesn’t feature the 50:22 law at all, nor does it include goal-line drop-outs.

The value of a try varies in the university competitions. The Varsity Cup awards seven points for tries that originate in the attacking team’s half, whereas the Varsity Shield favours the five-point value for all tries scored.

The seven-point try has proved difficult to monitor. This season, there have been several incidents where the final score of a Varsity Cup match has been changed a day later. Video analysis has confirmed where specific tries have originated, and thus what these tries are truly worth.

In round one of the 2022 Varsity Cup tournament, the University of Johannesburg secured a 44-42 bonus-point win against the Central University of Technology. The next day, it was revealed that one of CUT’s tries had originated in their own half, and was worth seven points instead of five.

CUT’s final tally was adjusted, and the result was changed from a UJ win to a draw.

The Varsity Cup has been used to trial various law variations since its inception in 2008. Lawmakers have used this tournament to innovate and experiment, with the long-term aim of implementing the more successful law variations at the higher levels.

Although a few misfires are to be expected, it’s hard to accept late changes to the scoreline and even to the results. It’s also a big ask for fans to monitor and understand these variations when the officials themselves are struggling to do so.

Red-card roundabout

According to reports in the UK, the 20-minute red-card sanction may be implemented in the European tournaments after the 2023 World Cup.

The news has been met with outrage in the northern-hemisphere rugby community. Many critics believe that players will push the boundaries – and compromise the safety of others and themselves – without a hardcore deterrent in place.

The proposal appears poorly timed and at odds with World Rugby’s drive to reduce head collisions and concussions.

The surge in yellow and red cards for high and reckless tackles has sparked another debate about the physical nature of the sport, and whether the spectacle suffers when one player is sent from the field. There’s a concern that defenders who make contact with a ball-carrier’s head by accident are suffering the same fate as perpetrators of blatant foul play.

World Rugby requires more data before taking a decision to implement the 20-minute red card across the board – hence the plan to stage further trials after 2023. This law has already been trialled in various South African competitions, and continues to be used in Super Rugby Pacific.

Different laws, different game

Although these issues are complicated, it can’t be good for the game to have so many tournaments favouring differing approaches to discipline and sanctions.

Right now, we have many versions of rugby playing out in various regions – and unless you’re keeping track of which tournament employs which law-set, you might not immediately recognise the ramifications of a particular action when it occurs.

If a player receives a red card in the first minute of a URC match, for example, that player’s team will be forced to compete with 14 men for the remaining 79 minutes. On the same day, in a match staged on the other side of the world in the Super Rugby Pacific competition, a player may commit the same offence at the same stage in the game, yet his team will be restored to its full complement of 15 men midway through the first half.

Rugby has been crying out for a global season for years. A move towards a more aligned calendar will have multiple commercial and player-welfare benefits.

A move towards a universal law-set – and a more consistent application of these laws – could also lead to a better understanding and appreciation of the game, and even a much-needed spike in interest. DM168

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper which is available for R25 at Pick n Pay, Exclusive Books and airport bookstores. For your nearest stockist, please click here.

Comments - Please login in order to comment.