CORRUPTION ANALYSIS

How State Capture led to human rights abuses — the case of Bosasa and the prisons

The impact of State Capture has to date mainly been assessed in financial terms. But the effects of endemic corruption are also directly felt in ways that amount to greater suffering on the ground — as Bosasa’s capture of the Department of Correctional Services illustrates.

Starting in 2004, and extending until 2019, the logistics company Bosasa won numerous contracts to supply services to South African prisons under the management of the Department of Correctional Services (DCS).

It began with a training contract. From there, Bosasa’s relationship with DCS expanded to include catering contracts, contracts for IT, TV and CCTV, fencing contracts, guarding contracts and more.

A number of these services — most notably, catering — had never previously been outsourced by the department. Former Bosasa COO Angelo Agrizzi told the Zondo Commission that company founder and CEO Gavin Watson had simply decided that he wanted to move away from providing catering to mining companies because the bribes involved were getting too big.

So Watson set his target instead on South Africa’s prisons, having identified two senior DCS officials — Patrick Gillingham and Linda Mti — who were ripe for bribing.

Although Bosasa would do lucrative business with a number of other state entities, it was the DCS that would prove the company’s real cash cow. Gavin Watson was no fool: in many ways the DCS was the perfect government department to target for widespread corruption.

Prisons researcher Dr Lukas Muntingh, from Africa Criminal Justice Reform (ACJR), told Daily Maverick that in some senses the DCS is “not really under control of the state”.

Muntingh described the department as notoriously “opaque”; report-backs to Parliament have long been criticised for being insubstantial, and in general, says Muntingh, it’s “hard to find out what’s going on”.

The Judicial Inspectorate for Correctional Services (JICS), currently headed by retired judge Edwin Cameron, does vital work investigating inmate treatment and prison conditions. But as JICS spokesperson Emerantia Cupido pointed out to Daily Maverick, “JICS doesn’t have insight into contractual and financial obligations between DCS and its suppliers”.

What the Bosasa saga reminds us, however, is that a more or less direct line can be drawn between corruption and the human rights abuses that often follow.

DCS: A history steeped in corruption

Agrizzi put it succinctly to the Zondo Commission: Bosasa ended up having “captured the department”.

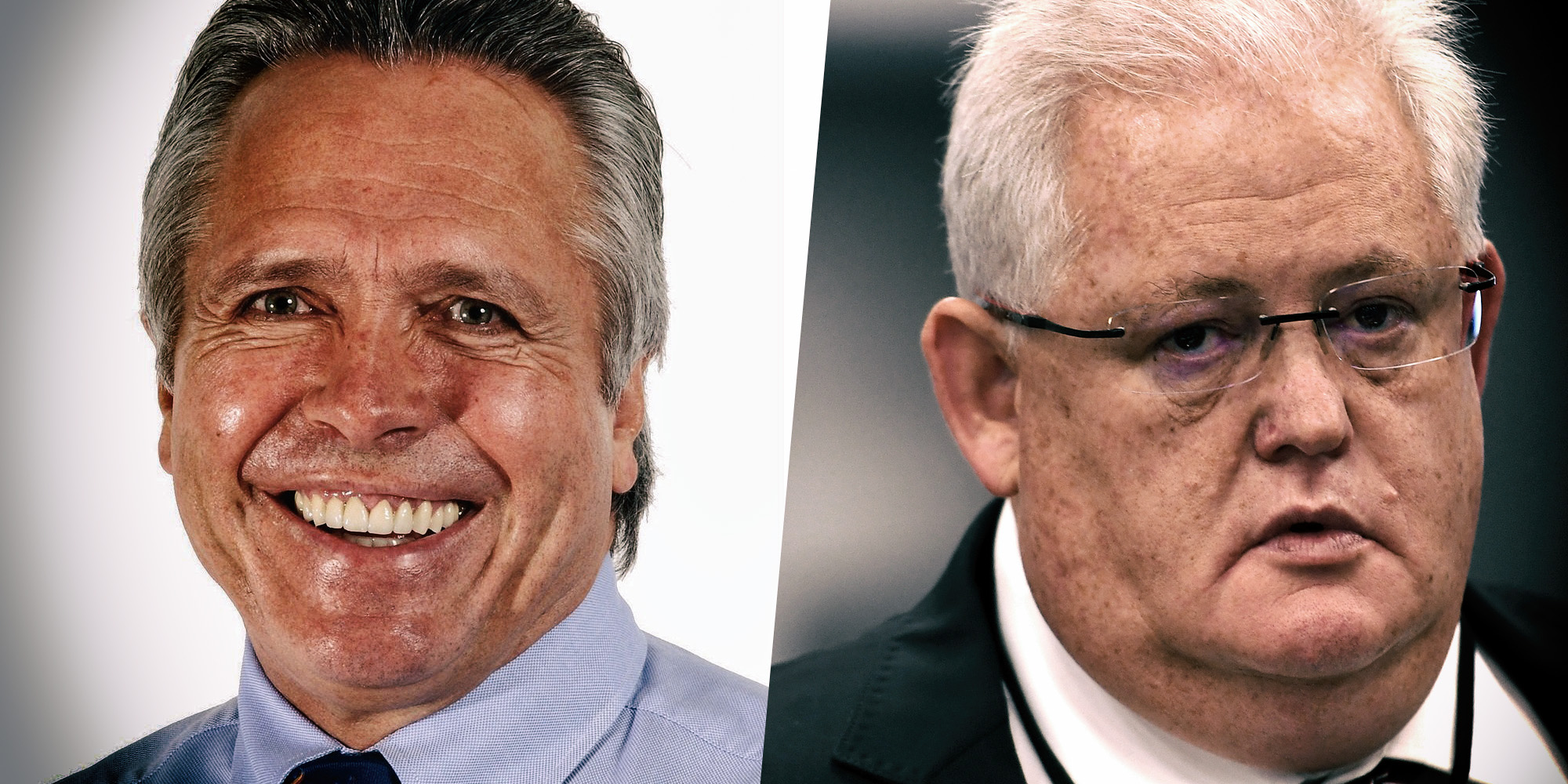

Bosasa CEO Gavin Watson. (Photo: Supplied) | Former Bosasa COO Angelo Agrizzi. (Photo: Gallo Images / Netwerk24 / Felix Dlangamandla)

One of the most astonishing things about this, Muntingh says, is that the Bosasa contracts “represent the second capturing of DCS within a few years”.

Muntingh was referring to the findings of the Jali Commission of Inquiry into Corruption and Maladministration in the Department of Correctional Services, which was established by former president Thabo Mbeki in 2001 following concerns raised as early as 1996 regarding corrupt activities occurring within the department.

The Jali Commission would end up releasing its final report in 2005, a few months after Bosasa’s first contracts with the DCS were inked, but well before Bosasa’s contracts would begin being illegally extended.

The commission found evidence of 20 previous investigations into the affairs of DCS, but the department had failed to implement recommendations made by bodies like the Public Service Commission concerning issues including overcrowding, the parole system and general corruption.

ACJR summarised the corruption-related findings of the Jali Commission as follows: “It was found that certain companies were consistently being awarded tenders… the required number of quotations for work was not adhered to, and officials were issuing orders without them having the authority to do so. The commission found that the department suffered substantial financial losses.”

But the Jali Commission also felt there was reason for hope: the national prisons commissioner at the time of the report’s release had not been in place when the major corruption occurred, and he was “endeavouring to reverse the situation”.

Sadly, the report could not have been more wrong.

Prisons commissioner Linda Mti — with the department’s chief financial officer Patrick Gillingham — would turn out to be the primary enabler of Bosasa’s corruption.

Mti’s support was viewed as so critical to Bosasa that the Zondo Commission heard he was still being paid off by Watson’s company a decade after Mti’s resignation from the top job in prisons.

Gillingham was eventually receiving R110,000 a month from Bosasa, and was “entitled” to an overseas holiday each year. Bosasa paid Gillingham’s divorce settlement and threw money at the problem when Gillingham’s son Patrick was implicated in fraud by his employer.

Both Mti and Gillingham received extras from Bosasa in the form of specialist golf clubs, imported Italian shoes, home furnishings, renovations, cars and even houses. Bosasa could easily afford this largesse due to the amount it was skimming off DCS contracts, Agrizzi’s testimony illustrates.

The cash cow catering contracts

When Watson set his sights on DCS in earnest, one of his primary targets was to get Bosasa involved in prison catering. Just one problem: South African prisons had always produced their own meals.

Muntingh says that this was one of the legacies of the apartheid government, which had “an obsession with the self-sufficiency of the prison system” due to its “sanctions mindset”.

But Watson had Gillingham and Mti on-side. Agrizzi testified to the Zondo Commission that at the beginning of 2004, Bosasa officials toured prisons “in plain clothes” — they were warned not to wear anything associated with the company — to do research to draw up the “blueprint” for an outsourced catering contract.

Agrizzi said he thought at the time that Bosasa was merely acting as a consultant for the DCS. But the research undertaken would actually become a specifications document, released by the DCS to invite bids for the outsourced catering of seven large prisons. Bosasa, of course, would win the contract.

The catering contract had what Agrizzi estimated was a 35% net profit for Bosasa baked into it. Pricing was manipulated, records the latest State Capture report, “by doubling the price of a special meal (the exact same as a normal meal, but prepared differently) and running the normal and special meals at a 70/30 ratio, instead of the [previous] 90/10 ratio”.

By 2013, when the contract was illegally extended for a third time, the value had risen to more than R420-million per year.

The outsourcing of prison catering raised eyebrows in Parliament’s portfolio committee, with members pointing to the fact that in terms of both the Constitution and the Correctional Services Act, the responsibility of feeding prisoners lay with the DCS and not private companies.

But the department always had excuses. Officials told Parliament that the relevant seven prisons did not have the resources or facilities to provide their own food.

One of the most outspoken critics of the practice was Cope MP Dennis Bloem, who told the Zondo Commission that from the outset he regarded the outsourcing as a “money laundering scheme”.

Bloem also pointed out that despite all the money paid to Bosasa for the contracts, all the food-related labour in these prisons was being undertaken by inmates — something confirmed by Agrizzi.

By the end of the 2016/2017 financial year, when the Bosasa catering contracts had been running for more than 12 years, the spending was beginning to affect the entire prison system. The DCS annual report for that year notes that: “The challenges experienced during the 2016/17 financial year was due to limited budgetary allocation… mainly in relation to outsourced nutritional services under Programme Care.”

The report states: “Sub-programme Nutritional Services under Programme Care exceeded its goods and services budget by R97.359-million (7.2%)”.

Yet — astoundingly for a service for which no previous need existed, and which was invented by Gavin Watson to milk the DCS — the outsourcing may have continued beyond the liquidation of Bosasa in 2019. In that year, the DCS was reported to be scrambling for new catering contractors to replace Bosasa.

DCS spokesperson Singabakho Nxumalo told Daily Maverick: “There are [today] no correctional facilities with outsourced catering services in South Africa.”

He failed to respond to a follow-up query asking when the practice was officially dropped.

Prison outsourcing gone wild

With the catering contract raking in millions in profit for Bosasa annually, Watson rapidly succeeded in expanding the services being provided to the DCS.

The Zondo Commission heard that the value of a prison’s access control contract was “inflated from the start”. The pricing of a fencing contract was similarly manipulated from the get-go.

A television contract awarded to Bosasa by DCS in March 2006, worth R224-million, was supposed to be for “developing and training of inmates”, but Bloem told the Zondo Commission that to date no education programmes of that kind have been rolled out.

Former Bosasa COO Angelo Agrizzi during his testimony at the commission of inquiry into state capture on January 22, 2019 in Johannesburg, South Africa. (Photo by Gallo Images / Sowetan / Alon Skuy)

At one point, Gillingham and Mti alerted Bosasa to the urgent need to come up with a new outsourced service. The third State Capture report states that the two DCS officials told Bosasa “that the DCS had surplus funds in their budget that they needed to use quickly in order to prevent it from going back to National Treasury”.

By October 2009, Parliamentary minutes record that the portfolio committee was “extremely concerned over the extent of the functions outsourced by the DCS”.

But Bloem testified that portfolio committee members also felt there were “more urgent issues” demanding attention, such as low salaries paid to prison staff and the problem of overcrowding in prisons. In reality, the rampant outsourcing to Bosasa was exacerbating these other issues.

“In prisons, there is really no strong argument for outsourcing unless it concerns some security functions — which is also a minefield,” Muntingh told Daily Maverick.

The impact of Bosasa corruption

For a company whose founders prided themselves on their strong Christian ethos — running daily prayer meetings and monthly all-night prayer sessions — Bosasa seems to have had very few compunctions about how its corruption would affect the often highly vulnerable people reliant on its services.

Beyond the DCS, the Zondo Commission heard how Bosasa skimmed money off a halfway house that the company was building for abused children, registering “ghost employees” on the payroll.

Its activities around the Lindela Repatriation Facility, which it ran for Home Affairs as a facility where undocumented migrants were housed before being deported, were perhaps the most shocking.

It used the facility partly as a way to raise cash for bribes. Bosasa ran the only telephone facility and the only canteen there, with cash takings estimated at between R300,000 and R400,000 per month.

Because Bosasa was paid per person staying in the facility, the Zondo Commission heard how the company would drive around police stations to pick up migrants for Lindela. As a result, the facility was often massively overcrowded, with residents crammed into inhumane conditions. One source estimated to the Mail & Guardian that as many as 7,000 people were detained at Lindela at one point, far beyond its capacity.

Despite becoming notorious for its conditions and the number of inmate deaths — 21 within one eight-month period in 2005 — Bosasa continued to run Lindela until its 2019 liquidation.

Within the prisons system, the effects of 15 years of Bosasa-driven corruption — and the precedents pointed to by the Jali Commission findings — are still being felt in ways that directly impact on the humane treatment of prisoners and working conditions for staff.

In March 2021, Parliament heard that the DCS would have to cut 10,000 jobs over three years. Of all South African correctional centres, only 35% were at that point estimated to be in a “fair to good” state.

Muntingh cautions that not all the problems which continue to plague South Africa’s prisons today can be traced back to Bosasa-style corruption: he lists poor management, lack of skills, a paucity of effective oversight and few consequences for rights violations as also contributing to the challenges.

But JICS spokesperson Emarentia Cupido told Daily Maverick that “the impact of the evidenced Bosasa corruption” on inmates’ wellbeing “is not hard to imagine”.

Said Cupido: “JICS daily witnesses defunct surveillance systems — which, we are told, were supplied by Bosasa — degrading infrastructure and defective maintenance. The money lost in corruption to Bosasa has a practical, daily impact on inmates’ welfare, though it’s difficult for JICS to put a finger on this.”

She added: “There can be little doubt that Bosasa corruption has burdened the entire correctional system in South Africa and that its sharp edge has fallen most severely, as in other sectors, on the most vulnerable, in this case, the inmates, especially the remand detainees”. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.