DAYS OF ZONDO, PART THREE

‘Bosasa simply had no shame’ – Watson brothers’ company hammered in State Capture report

The fact that the Zondo Commission devoted the entirety of the third instalment of its State Capture report to Bosasa is an indication of the breathtaking scale of the company’s corrupt activities. It is also a reflection of the extraordinary evidence given by the tainted witness Angelo Agrizzi.

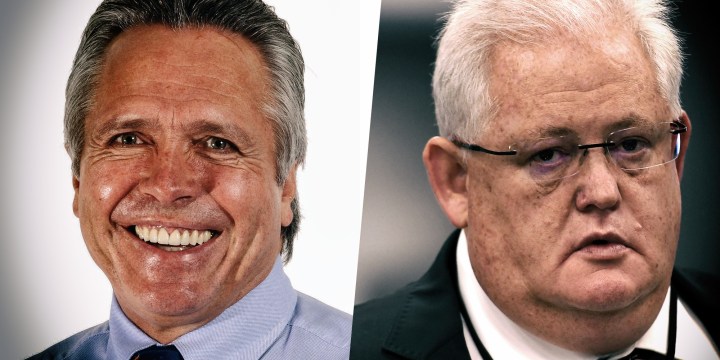

Bosasa Chief Operating Officer Angelo Agrizzi was the first witness before the State Capture Commission to set proceedings on fire. Agrizzi’s testimony laid bare the astonishing reach of a private company of which many South Africans had previously only been vaguely aware – and has provided the foundation for a third instalment of the State Capture report that surpasses its predecessors in the decisiveness of its findings.

Agrizzi was in many ways an unusual witness: one who gave deeply self-incriminating evidence and testified openly that he was both aware of and involved in corruption throughout his time at Bosasa. He captured public attention due to his unexpected candour and the unambiguous nature of his evidence: he told the commission, for instance, that there was no contract with the South African state won by Bosasa for which the company did not pay bribes.

As the latest State Capture report reminds us, his testimony was peppered with jaw-dropping details. That the unquestionably corrupt Bosasa founder and CEO Gavin Watson would lead the company in morning prayer meetings, for instance. That one of Bosasa’s many office money vaults contained a secret “drop safe” concealed beneath a picture. That Bosasa was shelling out between R4-million and R6-million monthly in bribes, helpfully recorded in Agrizzi’s “little black book”. That Bosasa paid for former Cabinet minister Nomvula Mokonyane’s 50th birthday party with the theme “Break A Leg”. (It turned out to be Mokonyane’s 40th birthday party, which she said she did not recall because she “would have preferred a better [venue]”.)

The fact that Agrizzi was able to supplement his testimony with corroborating evidence in the form of paper records, videos and photographs was an astonishing gift to the commission. But in other respects he was a less than ideal witness. Most notoriously, in a video played before the commission, Agrizzi could be heard referring to two black colleagues with the k-word.

“I am a racist. Judge me on that. I have admitted it and I am sorry,” Agrizzi told the commission at the time. He was taken to the SA Human Rights Commission thereafter. But his self-confessed racism left an indelible stain, and would later be used by Mokonyane in her defence: she argued that his testimony should be viewed through the prism of one who might be driven by his own bigotry to impugn the reputation of black Africans.

In Zondo’s latest report, he gives no sign of taking this claim by Mokonyane seriously. Indeed, the judge makes no mention of Agrizzi’s racism at all, which has to be considered a potential misstep given the number of critics eager to dismiss the State Capture findings on any basis whatsoever.

That is not to say that Zondo viewed Agrizzi as an unimpeachable witness. Zondo notes that Agrizzi’s evidence was both “contradictory in certain instances” and sometimes “fallible on detail”. Zondo also highlights the fact that the reasons for Agrizzi’s unusually candid testimony were not “exclusively public-spirited”, but probably motivated to a significant degree by Agrizzi’s fallout with his former boss Watson.

Since Agrizzi’s appearance before the Zondo Commission he has attempted to restyle himself in the fashion of a whistle-blower, publishing a book titled Surviving the Beast: The Ugly Truths about State Capture and Why They Tried to Kill Me. Zondo makes it clear he has little time for this Damascene conversion, writing that the least convincing aspects of Agrizzi’s commission testimony were the moments “where he tried to portray a less corrupt version of himself”.

On the “main pillars” of Agrizzi’s evidence, however, Zondo found there was “substantial corroboration”. This took the form not just of the supplementary records supplied by Agrizzi but also of confirmatory testimony to the commission by other former Bosasa employees.

“The evidence revealed that corruption was Bosasa’s way of doing business,” the report states succinctly.

“It bribed politicians, government officials, President Jacob Zuma and others extensively. Bosasa and its directors and other officials simply had no shame in engaging in acts of corruption.”

Bosasa’s reach was extraordinary. The company ran catering services, mining hostels, and youth development facilities. It won security contracts, fencing contracts, IT contracts, training contracts, transport contracts and more. It was involved in fracking and water quality audits. Even the Guptas’ South African business empire could not dream of such wide-ranging tentacles.

Other than through bribes – “bread rolls”, in Agrizzi’s mafia-style parlance – Bosasa won its contracts in some cases by writing the specifications for government tenders before being awarded them. In other instances, the company was given months of forewarning before tenders were advertised to carry out relevant research as an unfair advantage over other bidders. Emergency procurement loopholes were exploited; contracts were illegally extended.

The fact that Bosasa continued to be given state contracts despite media exposés, concerns from Parliament and a damning Special Investigating Unit report issued in 2012, Agrizzi attributed to the network of politically influential people receiving Bosasa’s patronage.

The attempts at influence by Bosasa, wrote Zondo, “were carried out at what may fairly be characterised as an industrial scale”.

Bosasa paid off the ANC, influential MPs and members of the executive. But the commission also heard how Bosasa’s favours extended beyond politicians to encompass the criminal justice sector. Agrizzi alleged that monthly payments were made to two key figures within the National Prosecuting Authority – advocates Nomgcobo Jiba and Lawrence Mrwebi – and at least one jurist, magistrate Desmond Nair, allegedly benefited from a Bosasa-sponsored security upgrade.

Zondo’s report finds that prima facie cases against all three of these individuals can plausibly be made.

Bosasa’s success also owed much to the networking aptitude of the Watson brothers, marshalled by Gavin, who died in a still mysterious car crash in August 2019. Gavin Watson’s voice was never heard by the Zondo Commission: Zondo notes that Watson did not seek leave to testify, never responded to a notice instructing him to file an affidavit, and none of Watson’s siblings have stepped forward to respond to allegations against him.

From the evidence presented at the commission by Agrizzi and others, we know that Watson enjoyed such an intimate friendship with former president Jacob Zuma that he considered himself “bulletproof”. He had quasi-paternal relationships with various ANC politicians’ children; as Energy Minister Gwede Mantashe eventually grudgingly acknowledged, Watson had even been awarded the “clan name” of Radebe.

Watson and his siblings were memorably described by MP Vincent Smith before the commission as members of the “patriotic bourgeoisie” who sought to assist politicians and activists to “re-establish their personal lives” after years devoted to the Struggle.

Behind closed doors, however, it seems that Watson had a more transactional view of his comrades. Code names used by Watson, Agrizzi and other Bosasa officials attest to this. Advocate Jiba was “Snake”, because she was fast and poisonous. Mrwebi was “Snail”, because he was slow. Mokonyane was the “Energiser Bunny”, because, in Agrizzi’s words, “whatever we needed done would be done”.

Cash was to Watson merely “Monopoly money”, to be used to secure Bosasa’s own “monopoly” over state contracts.

Zondo makes no findings against Watson, presumably because he is dead. Prosecuting the Bosasa CEO might, in any event, have been tricky business: he boasted about mistrusting paper and leaving no evidence of dodgy deals. Although Agrizzi was arrested on corruption charges shortly after his Zondo Commission testimony, Watson had not been arrested before he died. (Zuma gave the eulogy at his funeral.)

Also read: Dudu Myeni loved Louis Vuitton, especially when stuffed with R 300,000 Bosasa cash

To the corruption charges Agrizzi already faces, Zondo recommends adding potential charges of money laundering, fraud, and failure to report suspicious or unusual transactions. The report makes the same finding against a number of other former Bosasa employees.

Ultimately, wrote Zondo, there is “clear and convincing evidence pertaining to Bosasa of attempts to influence persons in the categories of office-bearers, functionaries and officials”.

For much of that evidence, South Africa has Angelo Agrizzi to thank: the deeply compromised witness who was arguably the best the Zondo Commission ever had. DM

Don’t miss our coverage of the first two State Capture reports.

Part 2 of the State Cape report – All about corruption at Transnet and Denel

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/9226″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

This surely should give the NPA enough leverage to start prosecuting.

The NPA has had enough evidence for months, even years. No high ranking anc deployee/cadre will ever be prosecuted, found guilty and jailed for anything. Maybe, just maybe one or two small-fry thieves may be sacrificed ‘for the greater good of the anc’ though.

All these cash donations are going to be hard to prove.

The auditor of Bosasa during that time ought to be ashamed of themselves.

D’Arcy-Herrman & Co – the auditors at the time. Mr Venter of D’Arcy-Herrman & Co admitted assisting in illegal payments from Bosasa through his own shelf company to a number of ANC hoods, and in fact through various intermediaries R500,000 to Cyril Ramaphosa for his 2017 ANC election campaign. Do not expect Cyril to lead the prosecutorial charge.

Angelo did the right thing