COMBATING GRAFT

The Case of Mozambique’s Manuel Chang: Civil society holds the corrupt to account

This is the first in a series of articles in which Maverick Citizen will examine how organisations in several countries across southern Africa are using the law to assert human rights, fight corruption and advance accountable governance.

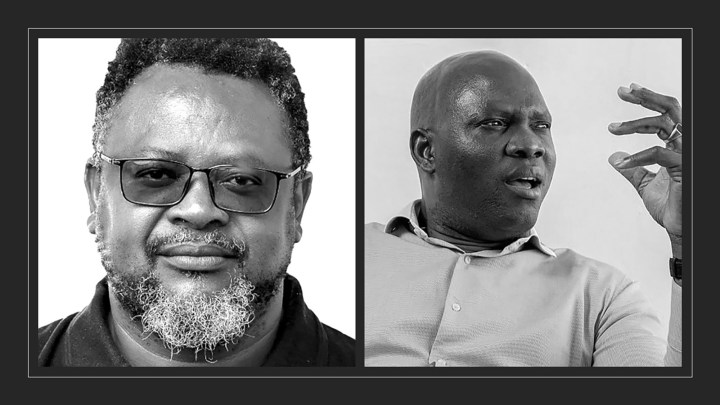

In this interview, we talk to leading Mozambican human rights defender Professor Adriano Nuvunga, the director of Mozambique’s Centre for Democracy and Development (CDD) and chairperson of the Fórum de Monitoria do Orçamento (FMO) (Forum for Monitoring the Budget, a coalition of 21 organisations), as well as Arnold Tsunga, the chairperson of the Southern Africa Human Rights Defenders Network.

They discuss the extradition case of former Mozambican finance minister Manuel Chang and the risks activists in Mozambique are facing in using the law to seek justice in a corrupt and captured state.

Mozambique’s former finance minister Manuel Chang. (Photo: IMF / Ryan Rayburn)

During 2021, one of the most interesting stories in the news was about the tug-of-war between the governments of Mozambique and South Africa over where Chang should be extradited to face corruption charges. The latest chapter ended in November 2021 when a High Court in Gauteng overturned the decision of Justice Minister Ronald Lamola to extradite him to Mozambique and ordered that Chang be extradited to the US instead.

Since then the Mozambique government has brought an appeal directly to the Constitutional Court, as well as an application for leave to appeal to the High Court. But in the meantime, Chang remains in prison in South Africa.

Mark Heywood: Can you tell us about the background to the case and the reasons you got involved?

Professor Adriano Nuvunga: When Manuel Chang was detained in Johannesburg en route to Dubai in 2018, human rights activists in Mozambique immediately saw an opportunity to seek justice.

It was the very first time that a politically exposed person from Mozambique was detained outside our country. When we learnt that he was detained as part of a request from the US, we didn’t think that the US justice system is better, or that we automatically want him to be tried there, but that this is a unique opportunity to have Manuel Chang face a serious and independent trial.

Mark Heywood: Who were the organisations that decided to bring an application before a South African court to try to prevent Chang’s extradition back to Mozambique? And what did you hope to achieve?

Adriano Nuvunga: The case was started by Fórum de Monitoria do Orçamento (FMO), an umbrella organisation of watchdog NGOs. FMO is a collective entity for Mozambican organisations who are pushing for accountability, transparency, human rights and fighting corruption.

In this case we have benefited from the regional networks and the support of the Open Society for Southern Africa.

To take advantage of an opportunity to ensure Chang faces justice, we needed to have lawyers.

But at the beginning, we have to admit, a mistake was made; that mistake was to use a commercial firm, rather than exploring public interest entities like the SADC Lawyers’ Association.

We only recognised this when we came across the Southern Africa Human Rights Defenders Network.

But at the beginning that knowledge was not there.

Arnold Tsunga: I think we have to look at it in context.

This case has always had an urgency. Most recently, on 17 August 2021, the decision (in terms of the Extradition Act No. 67 of 1962) issued by the minister of justice in South Africa, Ronald Lamola, to send Chang back to Mozambique created a sudden emergency from a public interest litigation perspective.

At that point there was a very minimum amount of time to consult on who could be the best entity to initiate the extremely urgent case. If minister Lamola’s decision to return Chang to Mozambique had been executed before it was challenged in a court of law, then challenging it was no longer going to be useful as it would become an academic exercise. The leverage of having him in a South African prison pending resolution of the litigation made the application necessary on an urgent basis.

This is the reason FMO saw taking public interest litigation as a necessary emergency measure.

People should understand that the idea of public interest lawyers is not something that is common outside of South Africa. The sudden emergency created wittingly or unwittingly by the minister’s decision to send Chang back to Mozambique made our Mozambique colleagues in civil society settle for the nearest available and accessible lawyers in South Africa to challenge minister Lamola’s decision.

In making a decision to extradite Chang to Mozambique, it appeared like the minister had not taken into account the responsibility of South Africa to contribute to fighting impunity from corruption in the Southern African Development Community (SADC) region. We felt the minister’s decision was reviewable and challengeable.

Because of that sudden emergency, we then asked ourselves: Which lawyers were closest to us to be able to do this? The legal costs factor did not rank as high as the question of the essence of time.

So the reality of the impact of high costs balanced against the beneficial value of litigation, and the amount of pressure that is put on a person like Professor Nuvunga as head of the Mozambican civil society group that worked to use litigation creatively, was not evaluated before the litigation.

It then brings about the question of the cost-benefit analysis before one chooses to settle for public interest litigation as a means of strategic advocacy — especially where defenders are put in a situation of potential exposure to costs that are personal while the benefit of litigation is public.

It kills the enthusiasm.

Mark Heywood: How has this case unfolded?

Arnold Tsunga: In terms of the key events: It started with the request by the US via a warrant for his arrest which led to his detention in November 2018 in Johannesburg.

After he was arrested the Mozambique government tried to be clever. They also said, “No, no, no, we also want him [to face corruption charges in Mozambique]”.

So that way they created a semblance of contestation around jurisdictions as to who has the better right to extradition. It created an impression that South Africa had a choice between either extraditing Chang to the US or to Mozambique.

Immediately in the minds of simplistic persons, the mentality would be, “no, no, no, no, no. Why [extradite an African leader] to the US and not to an African jurisdiction?”

But deep down the Mozambican human rights defenders were saying, “what we want is for Chang to be extradited to a country where he will be genuinely held accountable for his role of stealing money from public coffers through an independent judicial process”.

So it was about accountability. The choice between US or Mozambican jurisdiction became an incidental component of the decision-making process.

The Mozambican defenders came to the conclusion that since Mozambique had not issued a warrant for his arrest, and had not shown any prior interest to prosecute him, it therefore meant that their issuance of a request for his extradition (after he had been arrested in South Africa) was a political as opposed to an accountability tool. Their aim was to facilitate impunity and prevent Chang from being able to account for his role in the stealing of huge sums of money from public coffers.

In the minds of the Mozambican defenders, it was a choice of how best to get Chang to account. They settled for the US as the best option for accountability since Mozambique has been proven to be a geography of impunity when it comes to political corruption.

So when minister Lamola made his decision in August 2021 that it is extradition to Mozambique, it was clear that Mozambique was a choice of impunity. While Mozambican defenders do not support Africans being tried in Western countries as a matter of principle, or may not support the US justice system per se, they were convinced that the US was the jurisdiction where there was a reasonable prospect of Chang being made to give a blow-by-blow account of his role in stealing billions of dollars from Mozambican public coffers.

In short, it was a choice for accountability rather than a choice of the American judicial system. That was the only reason Mozambican defenders challenged Justice Minister Lamola’s decision. And that’s the reason it’s still being challenged.

It’s not that African defenders don’t believe in African justice or that American justice is superior to justice in Africa.

Minister Lamola’s decision appeared to show clearly that South Africa was not taking into account its serious responsibility of fighting corruption inside and outside South Africa and holding leaders to account for their role in use of public funds. Mozambican defenders felt this case needed to be challenged in South African courts for a second opinion. When South Africa was almost on the verge of extraditing Chang to a geography of impunity, Mozambican defenders thought, “it can’t be on our watch!” They rushed to the nearest available lawyer. The lawyers got the result they wanted. But the pain of looking for money to pay legal fees is now suffered by a few defenders like Professor Nuvunga.

The development partners seem not to have wrapped it around their heads, how important it was to support this case in order to create an example that even if Mozambique is a geography of impunity for corrupt officials, a safe environment for thieves, it is not the same in countries outside Mozambique.

Mark Heywood: How much public support and understanding for the work that the FMO has done on this case is there locally? Is there a lot of media interest in it?

Professor Adriano Nuvunga: The media here is highly polarised.

The mainstream media is dominated by the Frelimo establishment, directly and indirectly, including the privately owned media. You have ministers who have bought shares with the independent media. It is not independent, as they claim to be.

But even in this context, we still have media covering daily the FMO, you have people supporting this. So, FMO is a popular entity. But it is more supported by the ordinary people in the streets, in informal circles; we have a whole lot of people saying, “well done, well done, keep it up”.

We feel the support. We feel encouraged by the wider public. But the small, elite-centric media and commentators, of course, say all sorts of things.

Mark Heywood: Are there threats to your personal safety?

Professor Adriano Nuvunga: We have used the legal avenues, we have used the courts, in a context where we know — particularly in Mozambique — this means going against an entrenched system. The political elite want Chang brought home as a matter of their national interest.

We are going against it. By demanding that those who control public resources should be held accountable, we were really putting ourselves in situations of being persecuted, including being shot at any time. There are a number of threats that were made last year, including threatening to put bombs in my house.

As I’m speaking, my family is temporarily relocated out of Mozambique for their safety. It creates a difficult personal social and economic environment as I have to travel each and every time I want to meet them.

But leadership is a choice. We have made the choice of doing the right thing, of pushing things in the right direction. Being a human rights defender is a choice. Once you have made that choice you have to bear the consequences of that.

But at the moment we are feeling that we are left on our own.

The costs to keep the Chang case going are beyond our capacity.

The Mozambique government will appeal and they can easily pay and our attorneys will ask us to make the payments we do not have and I don’t know where we get that money.

So this is really frustrating.

We have the capacity to utilise the existing infrastructure, the law and the courts, but the costs of litigation are beyond our capacities.

There is an aspect of personal risk. One day I will invite you here to take you through the security system that I have in place. This is very expensive and I have to take that from my own pocket.

We were keen to participate in this interview because it may help to put this case in the global domain. We want it to be known, we want this case to encourage other charities globally, to use the law and use courts to pursue justice for their people and societies.

But we also feel that this can be used to strengthen our protection a bit.

Mark Heywood: What is the cost of the litigation so far?

Adriano Nuvunga: The initial fee was around $20,000. Initially an agreement was reached for a one-off payment, but that was not knowing that we would have all these appeals and that all these appeals would mean new payments had to be made. Each and every time the amounts are going higher and higher.

We thought, as is the case in Mozambique, that if you agree on a fee structure that covers the whole case, even if there are appeals, those appeals are covered in the framing of the agreed payments. We did not know that each and every time that would require new payments. Now the outstanding bills are more than $50,000.

Arnold Tsunga: For the preparation of the papers to oppose the appeal we have to pay a deposit of R325,000. The lawyers have told us that to go to the Supreme Court it’s R700,000. And then if the matter goes to the Constitutional Court it will be another R700,000. So the costs are coming to about R1.7-million, which is well over $100,000.

Mark Heywood: Does that mean that if you can’t raise this money, you can’t oppose the application for leave to appeal? And that then jeopardises everything that has been achieved so far and Manuel Chang has a better prospect of avoiding justice?

Adriano Nuvunga: Exactly, this is where we are today.

Mark Heywood: There is another anti-corruption case you are involved in, challenging toll gates on roads in Maputo. Can you tell us what this case is about?

Professor Adriano Nuvunga: This is one of Mozambique’s biggest corruption cases.

The government has decided to build toll gates throughout the country. Just to give you an example: we have a ring road in Maputo that is 50km long. It goes around Maputo city and connects with what we call the “corruption bridge” (the longest suspension bridge in Africa that links Maputo and Katembe) that the government has built. They put four toll gates in an area of 50km. These toll gates are within Maputo city.

How can we have toll gates within the city? The population is already impoverished by the illegal debts.

This is part of the story.

The second part is that they have created a private entity. They have moved the management of the toll gates from the state entity to a public-private partnership entity with no money! They haven’t invested a single coin yet they have given 20% of the shareholding of that entity to themselves! So this is a case where they will collect people’s money daily with zero investment. This money goes to the pockets of the ministers.

So we are saying it should be stopped, this cannot continue, and this is the fight.

When we went to court to deliver the petition, I found 110 heavily armed police escorting me, stopping me from talking to the media and threatening me. I told them, “You want to shoot me, shoot, but I will enter this building to file our case against the state. This is incorrect.”

We went to the Administrative Court because that is the level of the legal system where you start with the process. To bring an action aimed at building a public interest enterprise you start with this court.

We are concerned that the case will not be successful because in the Mozambican context, the public perception is that the judiciary is undermined by Frelimo. But at least we are not stopped from using the judicial infrastructure.

Mark Heywood: In conclusion, what lessons would you like people to draw from your use of the courts for social justice?

Arnold Tsunga: It is important to look at how the Mozambique Human Rights Defenders’ Network, and FMO, the organisation on anti-corruption that Professor Nuvunga is leading, have been creatively trying to use litigation inside and outside Mozambique.

Their aim is to try to achieve results around public accountability. Therefore, they are using public interest litigation as a strategic tool for transformation of our societies.

But it has been a very lonely situation for the professor at the level of costs. Because it’s one thing to say that impact litigation is very useful to bring about public accountability. But in real terms, you must understand the sleepless nights and the headaches that the professor has been going through in terms of just getting development partners to support FMO to be able to carry out that type of work.

He has absolutely no personal interest in it. The results and final beneficiaries are not just the people of Mozambique, in terms of accountable governance, but also a better SADC region, both in terms of the role of the judiciary and in supporting human rights defenders to be able to entrench a culture of accountability and accountable governance.

Ordinary people, in particular human rights defenders, suffer at two levels.

The first level is that when you confront power you run the risk of the consequences associated with speaking to power. This can include great personal sacrifice, attacks and some people get killed.

But you also then run the risk of liquidation because the amount of legal fees that have now been asked for causes sleepless nights.

It’s an existential threat in a way, an institutional existential threat because to be asked to pay $50,000 just for one case is quite a shock to the system. Then donors are not willing to come across to support that. But they expect human rights defenders to be impactful and effective.

How do we deal with that?

Development partners need to account to us on how much they’re committed to defending and strengthening democracy and accountable governance. How much are they committed to supporting human rights defenders like Professor Nuvunga who take the risk to handle the bull by the horns in an environment where we have a history of defenders being attacked and executed on the roads of Maputo?

So that is why I thought this is an important conversation. It may achieve wider publicity of the strategy of using the law to protect communities. But it also shows the risks that defenders face. But also the costs, in terms of financial costs and also in terms of the risk.

So that’s where we are and I want to place that on record!

Mark Heywood: I agree, I don’t think international development partners can talk about supporting clean governance and accountability, and then not be prepared to help pay for struggles that pursue those objectives. DM/MC

The extradition of Mozambique’s Manuel Chang: A timeline

Here are the events leading up to and after the arrest of Mozambique’s former finance minister Manuel Chang – who remains in a South African prison while a far-from-finished court case unfolds that will determine where and whether he faces justice.

A timeline of events:

2005 to 2015: Manuel Chang serves as Mozambique’s minister of economy and finance in President Armando Guebuza’s Cabinet.

29 December 2018: Chang arrested at OR Tambo International Airport on allegations of diverting loan funds in a corruption scandal, based upon an indictment in the US.

29 January 2019: US submits a request to South Africa for Chang’s extradition. A few days later (1 February 2019), Mozambique submits its own warrant and request for extradition.

January 2019: South African judge confirms legality of arrest after application by Mozambique to declare arrest unlawful.

February 2019: Then International Relations and Cooperation Minister Lindiwe Sisulu tells Daily Maverick that the government has acceded to a request from Maputo to extradite Chang.

21 May 2019: Then Justice Minister Michael Masutha announces decision to extradite Chang to Mozambique, mainly on the grounds that since the alleged crimes were committed there, that was the logical place to put him on trial.

May 2019: Mozambique’s Fórum de Monitoria do Orçamento (FMO), a coalition of NGOs, launches a court application in South Africa to overturn Masutha’s decision.

13 July 2019: New Justice Minister Ronald Lamola’s office announces that he has halted Chang’s extradition to Mozambique and is seeking a high court order reversing Masutha’s decision. Lamola also announces that he is opposing Chang’s application to be extradited to Mozambique, and will not oppose the FMO’s application.

1 November 2019: A full Bench of the Gauteng High Court sets aside Masutha’s decision to extradite Chang to Mozambique as well his decision to dismiss the US’s extradition request. Both decisions are “remitted to the current minister for determination”.

2020: Chang remains in prison in Johannesburg.

May 2021: Reports surface of differences between factions in the South African Cabinet over where Chang should be extradited. Ministers associated with the former president support extradition to Mozambique.

May 2021: A protest by civil society calls on Lamola to speed up his decision on Chang’s extradition to the US. Lamola’s spokesperson, Chrispin Phiri, responds to questions from Maverick Citizen, saying:

“The Minister is considering various legal opinions on the interpretation of the various applicable laws. These laws vary from the African Charter on Human Rights and Peoples rights (sic), and the SADC protocol. Depending on the legal instrument at hand, one is required to determine the extent of the instrument’s domestication. The information at hand requires the Minister to consider various aspects of international and regional law alongside our Constitution.”

23 August 2021: Lamola announces that Chang will be extradited to Mozambique.

24 August 2021: The FMO launches an urgent application at the Johannesburg High Court for an order to prevent Chang’s extradition.

10 November 2021: High Court Judge Margaret Victor overturns Lamola’s decision.

December 2021: Mozambique seeks leave to appeal the high court’s decision on extradition to the US, and brings a separate direct application to the Constitutional Court. DM/MC

The November 2019 judgment in the Chang case, in which the Gauteng North High Court ordered the South African justice minister to reconsider the decision to return Chang to Mozambique, is here: Chang v Minister of Justice and Correctional Services and Others; Forum de Monitoria do Orcamento v Chang and Others (22157/2019; 24217/2019) [2019] ZAGPJHC 396; [2020] 1 All SA 747 (GJ); 2020 (2) SACR 70 (GJ) (1 November 2019)

The judgment of 7 December 2021, in which the court ordered that Chang be extradited to the US (and not Mozambique), is here: Press Release: Judgment Delivered In The Matter Of Manuel Chang’s Extradition — Helen Suzman Foundation

For further reading on the crisis of corruption in Mozambique and civil society’s response, see: Mozambique: Poverty and inequality fuel violent extremism (Part One); Mozambique: What next for Cabo Delgado — dialogue or disaster? (Part Two); Mozambique society sceptical of Manuel Chang facing justice over hidden debt scandal

The work to produce this article is supported by the German federal foreign office and the Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen (IFA) Zivik funding programme. The views in this article do not represent those of the German federal foreign office or the IFA, and these entities have had no involvement in the production of the content.

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/8976″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.