OUT IN AFRICA (PART TWO)

‘We exist’: Photographic project sees Maputo’s marginal ‘others’ stepping boldly into the spotlight

A series of four articles examine issues of policy, laws, rights, culture, popular culture, language, stigma, crimes, discrimination and individual experience of the queer community in four African countries.

On a balmy day in October this year, the front lawn of Maputo’s German Cultural Centre was a hive of activity as a small team of people went about assembling an outdoor exhibition. Caio Simões de Araújo, who headed up the team, remembers inquisitive folk walking by — “actually coming over, asking us, ‘Where are these pictures from?’ Because they don’t really imagine that this exists in Maputo, you know. They don’t really know.”

Titled “Outros Corpos Nossos (Other Bodies of Ours)”, the exhibition — which also served as the launch of the eponymously titled book — was, certainly by Mozambican standards, not run-of-the-mill art world fare. It featured images of Maputo’s marginal ‘others’ — the city’s queer folk.

By way of introducing the project, the book’s sleeve notes read: “Other Bodies of Ours follows a group of queer artists and activists as they carve out for themselves a space in the world, and in the city. The texts, photographs, portraits and testimonies comprise a living and lived archive of queer narratives in Maputo.”

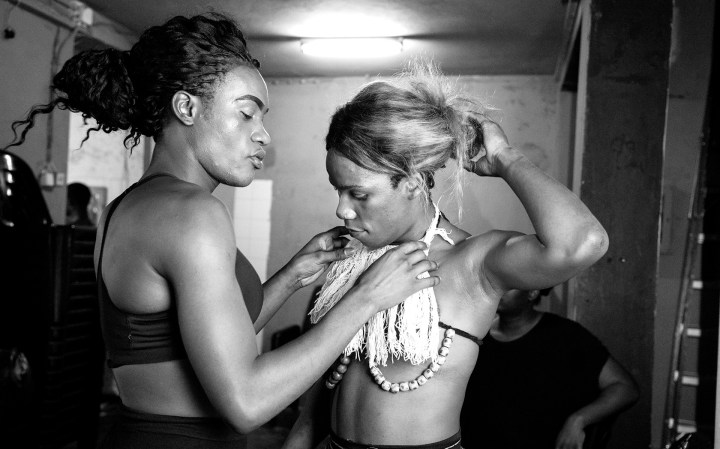

One of the images from the book, ‘Other Bodies of Ours’, which celebrates Mozambique’s queer communities. (Photo: Aghi)

Fielding the questions of curious passers-by was something that Simões de Araújo and his team were more than happy to do. The decision to exhibit the work outdoors was, after all, taken for more than merely having to adhere to Covid-19 protocols. There was also, behind this decision, a more political motivation.

“A very powerful aspect of the project is to try to encourage this kind of visibility,” says Simões de Araújo. “This is actually something that Lambda [Mozambique’s oldest queer rights organisation] has been working on for many years. They call it ‘positive visibility’. It aims to kind of reorient the ways in which queer life is represented. To take it away from the negative tropes of disease, suffering, death and things like that.

“So, this was a very integral part of the project and very much what the book intends to achieve in a more kind of, you know, political sense. That is the purpose.”

Although same-sex relations in Mozambique were decriminalised in 2015, the book asserts that, for the country’s queer communities, the need “to affirm ‘we exist’ remains as important as ever”.

A 2020 report by Human Rights Watch found that, although a 2017 court decision declared the government’s refusal to register Lambda as an organisation “unconstitutional”, the government has yet to do so.

The report also found that “despite authorities showing some tolerance for same-sex relations and gender nonconformity, LGBT people continue to experience discrimination at work and mistreatment by family members”.

Simões de Araújo says the project was initiated in 2019 as part of a broader oral history project, “Archives of the Intimate: Queer Oral Histories of Maputo, Mozambique”, which was carried out in partnership with Wits University’s Governing Intimacies Project and the GALA Queer Archive.

“I did my PhD on Southern African history with a focus on Mozambique,” he says. “So I’ve been going back and forth [between South Africa and Mozambique] for research for some time.”

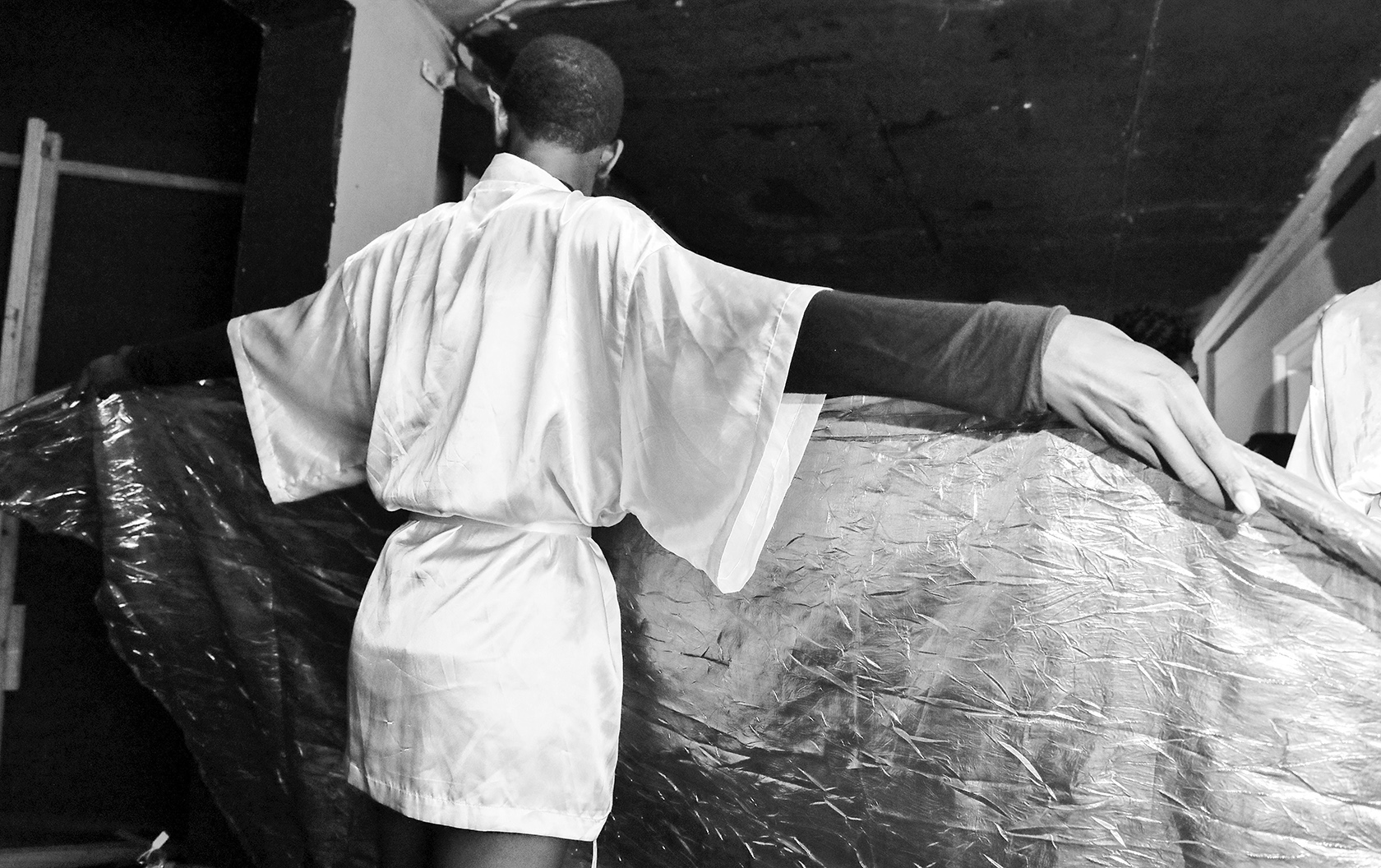

The parties and social gatherings put together by queer rights group, Lambda, are seen as ‘safe spaces for experimentation and self-expression’. (Photo: Aghi)

It was during one of his visits to Maputo that Simões de Araújo was introduced to an aspect of the city he had, until then, not been aware of.

“I was interviewing people and being part of events; being part of the queer cultural scene. And they had this event going on by the Lambda cultural group, which they call a cultural soirée. And I went to this event and, you know, it was very eye-opening for me because it was the first time I was seeing this type of event in Maputo, where they did drag shows and voguing and theatre and poetry and all of that.

“After that, I met the photographer, really very much by chance, because he was a friend of a friend. Anyway, I told him about the event I had just gone to and he was also very interested. He is also queer [but] had also never witnessed anything like that in Maputo. So that was very much how the project started: out of coincidence, frankly.”

These coincidences melded together to birth a 160-page book brimming with images and first-person testimonies (in Portuguese and English) that are, at once, insightful, tender, celebratory and, moreover, unapologetically political.

Divided into three sections, the book kicks off with behind-the-scenes shots of a performance by the queer cultural group, The Untouchables, at Maputo’s Teatro Avenida. Titled, “Onde Eu Me Encontrei (Where I found myself)”, this first chapter shows us queer boys, girls and gender-diverse in-betweeners applying make-up, doing last-minute sewing repairs to well-worn wigs, scoffing greasy take-aways from polystyrene holders, fixing each other’s outfits or simply staring proudly into the camera.

“It was through dancing that I had the courage to show society that I am trans,” Drica, one of the performers, reflects in the book. “People used to think it was a number; that I made it up… People would ask me, ‘What number was that?’ And I said, ‘No, that person you saw on stage is not a character, it is my identity.’ It was in dancing that I found myself; that I could free myself, and accept myself.”

The second chapter, “Achados e Perdidos (Lost and Found)”, documents Maputo’s queer party scene. Although accurately capturing the joyful nature of all-inclusive queer events, the images go beyond the mere documentation of revelry. There is a strong sense of community here. Couples hold hands or stare coquettishly at the camera. On the dancefloor, there is laughter, bums are pushed seductively into groins, and hands are held aloft in glee. A person of indiscriminate gender twerks on a pool wall as others cheer them on.

“The first time I went to an LGBT party… that was impactful. Why? Because I realised that, in my country, there were many of us, and that we could meet, and live and share that moment together. And in the midst of all this fun, we talked [and] shared impressions [and] that contributed to the formation of my personality,” Paixão, one of the revellers, states.

The parties were initiated by Lambda as “safe spaces for experimentation and self-expression”. Frank Lileza, Lambda’s public relations officer, says the events were started in 2008 and are held annually on significant days in the queer calendar — International LGBT Pride Day (28 June), International Day Against Homophobia, Transphobia and Biphobia (17 May) and Lambda’s birthday (13 October) — as well as one end-of-year shindig.

Tyfane, one of the participants in the project, says: ‘My beauty is a protection, my shield, because I need it. If it wasn’t for this, I wouldn’t have the strength to get out on the street.’ (Photo: Aghi)

“You know, Mozambique is kind of, like, a place where LGBT people are very introverted,” says Lileza. “Having such spaces — and being LGBT generally — is not easy because people do not understand. So the parties are for getting all the LGBT people together in one event. Just for a safe environment.”

Titled, “Meu Espelho (My Mirror)”, the book’s third chapter is, by far, the most powerful. Featuring the portraits of queer folk on the streets of Maputo, this chapter offers the reader a closer look at the inner world of some of the individuals captured in the preceding two chapters. Removed from backstage antics and anxieties or dancefloor shenanigans, it is in these portraits and the accompanying text where they share with the reader moments of self-discovery, defiance, joy, vanity and pride.

“It was a unique experience,” Paixão reflects. “I had never had the opportunity to pose like this for the cameras. And I didn’t feel shy. I think people have to start realising that we [can] also do actions like this, out in the open. So, for me it was good that people could also see that we are in fact fighting for our rights through these photographs.”

For the photographer, Aghi, shooting these portraits on the streets of Maputo was “fantastic… nobody bothered us”.

“It has been a very powerful and creative expedition, taking possession of the city and animating it with our creativity,” he says. “Once, we shot in front of a laundry and the workers wanted to have a group photo with us. Shooting on the street has always been a blessing.”

Based between Maputo and Berlin, the Italian documentary photographer, says the most rewarding aspect of the project was getting to show the participants their images.

“I put together a dummy with all the pics and went throughout the city and surroundings on my motorbike to show the work to all the people in the book and ask them to sign authorisation. Everybody was looking at this notebook with such attention and emotion and saying they were satisfied because ‘everybody was there’. That was touching… such a good memory.”

For Simões de Araújo, conducting a second round of interviews with the participants in order for them to share their thoughts on their images as well as the experience of being photographed, was an essential element of the project.

“This was something that we really wanted to do with this project, and something that… is a bit unusual. And it’s unusual because it really does take a lot of work. It was very challenging because, you know, obviously it takes time, it takes effort. But for me, that is the most interesting part of the book, because you seldom see that.

“You seldom see people speaking back to the ways in which they are represented. But I also think that was the most rewarding part of the entire project. And I think those are the most beautiful conversations in the book: when people are speaking about their photographs.”

‘When I look at a picture like this, I feel like I’m a public figure. I think that my dreams are coming true, bit by bit,’ says Minaj. (Photo: Aghi)

Lileza says that, for the participants, being involved in the project made them feel “empowered”.

“They feel great,” Lileza says. “They feel somehow recognised. So it was a very nice way of empowering queer and trans people. Because many people don’t know that trans people exist. They always engage trans women as drag queen dancers, because they do dance and stuff. So it was important to show that it’s not only about the [dance] shows, but it’s about the identities.

“It’s about something that we have to embrace. It’s an identity we have to respect and we have to empower them to be as they are. So I think the exhibition helped with that.”

“I really hope,” says Simões de Araújo, “that the book gives people a sense of what queer life in Maputo is like in a very visceral manner. Because the pictures speak about this dimension of affection, sentiment, community and viscerality. Because they always speak from the point of view of the body.

“You know, you have the body dancing, you have the body posing. There is this friendship, this joy. And I think that is really important. Because those are images that people do not often associate with queer experiences and queer lives and biographies on the continent — and especially not in Mozambique.” DM

To order a copy of “Outros Corpos Nossos (Other Bodies of Ours)”, email [email protected] Alternately, download the PDF here.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.