#BRINGBACKOURBONES

Remains to be seen: Zimbabweans believe Britain can help solve the mystery of the missing skull

For years Zimbabweans have been calling on Britain to return the skulls of a former spiritual leader, Mbuya Nehanda, and several chiefs who were killed during the First Chimurenga, an Ndebele-Shona revolt against the British South Africa Company’s administration that took place in 1896-97. Now, a #Bringbackourbones campaign has been launched.

Perhaps not far from where Mbuya Nehanda’s statue looks out across downtown Harare, lies the answer to the 123-year mystery that surrounds her death.

There is the possibility that somewhere within the city limits of Zimbabwe’s capital lies her secret grave, and finding it could prove once and for all whether her head was indeed removed and sent to England.

For years Zimbabweans have been calling for the return of skulls that belonges to the spiritual leader Nehanda and several chiefs who were killed during the first Chimurenga, an Ndebele-Shona revolt against the British South Africa Company’s administration that took place from 1896 to 1897.

Many Zimbabweans suspect the skulls are being kept in the British Natural History Museum in London.

Recently a group of Zimbabweans, including other from the diaspora, organised what they called the #Bringbackourbones campaign. There have been several protests over that last month. One of them was at the British High Commission in Pretoria.

“The (Zimbabwean) government is making an effort but we feel they are not moving fast enough,” explains Vusi Nyamazana, a spokesperson for the group. “In our culture, the spirit will hang in limbo because the body has not been buried properly.”

He added that these restless spirits have been haunting the dreams of some Zimbabweans.

The Zimbabwean government had formed a repatriation committee. In 2015, then president Robert Mugabe called for the skulls to be returned from the British Natural History Museum.

But there is a problem. The museum, after trawling through their collection of 20,000 human remains, couldn’t find any evidence of the skulls the Zimbabwean government was looking for.

They did, however, come across something else.

“We have the remains of 11 individuals from Zimbabwe, but after extensive research have found no evidence to suggest that they are the remains of Mbuya Nehanda or others associated with the First Chimurenga,” a statement from the museum’s press office read.

“We have shared all the information we have with the authorities in Zimbabwe and are continuing discussions with the Zimbabwean government and hope to host a delegation in 2022 to discuss the repatriation of the remains we do hold.”

Nehanda was said to have a powerful influence not only during the First Chimurenga, but also later, during the fight against the Rhodesian government.

The executive director of the national museums and monuments of Zimbabwe, Dr Godfrey Mahachi, believes it is difficult to understand the Zimbabwean war of liberation or the Second Chimurenga without acknowledging the role Nehanda played.

“Ritually, everything that happened during the war of liberation was done in the name of Nehanda… it was her spirit that was supposed to look after the fighters as they fought the struggle,” says Mahachi.

Nehanda is believed to have been born around 1840 in what is now the Chishawasha district in central Mashonaland. It is said that she became possessed by the Nehanda spirit, which for the last couple of hundred years used women as its medium.

In 1894, the British South Africa Company introduced a hut tax. Two years later it sparked a revolt by both the Shona and Ndebele. Nehanda, who had become a powerful figure, encouraged the uprising.

Colonial forces eventually suppressed the uprising using machine guns for the first time to mow down charging impis.

Towards the end of the rebellion, Nehanda was captured and charged with the murder of native commissioner Henry Hawkins Pollard.

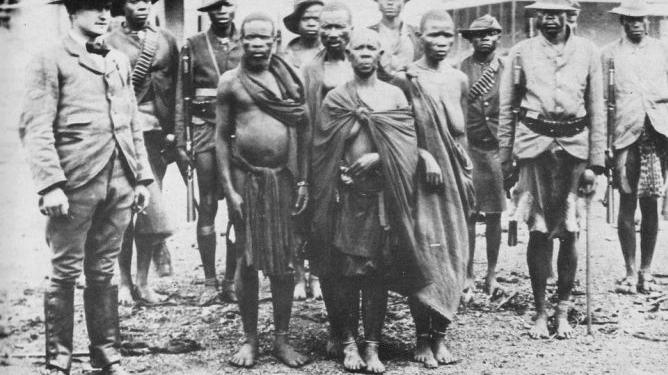

There is a photograph of Nehanda, a diminutive, emaciated woman staring defiantly into the camera, even though she had just learnt she was about to die. Around her are armed black colonial troops.

The photograph was taken outside the court where she had just been convicted of murder and sentenced to hang.

Not long afterwards, she was put to death – and that is where the myth began. Her burial place was kept secret so as to prevent it from becoming a shrine.

Next to nothing is known about her burial.

“I don’t know of any evidence that the heads of the spirit mediums Nehanda and Kaguvi were taken after they were hanged in 1898. I don’t think any of the serious historical works on the 1896-97 rebellion, such as by TO Ranger, David Beach and Julian Cobbing, included anything about that. I think Ranger would have included this,” says historian Prof Timothy Stapleton of Trent University in Ontario, Canada.

He adds that he suspects the recent demands for the repatriation of skulls is another attempt by ZANU-PF to use the memory of colonial conquest and African resistance to bolster its legitimacy as a ruling party in Zimbabwe.

Historian and trade unionist Dr Takavafira Zhou said he also didn’t know of any evidence that Nehanda’s skull had been taken. However, there is evidence of other chiefs having their heads taken.

Historian Denver Webb believes it is not impossible that Nehanda’s skull and those of the chiefs were taken to the UK, and could well be somewhere in the British Natural History Museum.

Webb has delved into the human skull trade, which he discovered was thriving in 19th century southern Africa, particularly in the Eastern Cape, where heads were taken during the various frontier wars.

“It just became a common colonial practice… a way of dominating people,” he explains. “So in 1877, colonial soldiers (in what is now the Eastern Cape) took the heads of warriors and boiled them, then tied the skulls to their saddles as a show of bravado and contempt for the enemy.”

Heads were taken not just as souvenirs – they were also collected in the name of science. Scientists were seeking out skulls to bolster the race theories of the day.

“It wouldn’t surprise me that the skulls were taken to the British Natural History Museum, as they tended to keep such skulls with the animal specimens,” says Webb. The problem, he explains, is that many of these skulls that are sitting in collections don’t have much of a provenance.

Details of who the person was and where the remains came from are often sketchy.

“I think they could also be in museums in Scotland, Cambridge, Oxford. They could be anywhere, because people took them as individual collections. Then they would give them to their local museum.”

Just as with Nehanda, there was a myth in South Africa that centred around the missing skull of one of the great Xhosa kings.

King Mgolombane Sandile was shot and killed during the ninth frontier war. The story was that his head was taken.

Evidence for this was a skull that sat on the mantelpiece of Major General Sir Frederick Carrington’s Cotswolds home, in the English countryside.

The officer had fought in the ninth frontier war and claimed that the skull belonged to Sandile.

Later, after his young bride complained of the gruesome memento, he had it buried in the garden alongside the graves of his two pets.

He even erected a tombstone that read: “Here lies the head of Sandilli. [sic], chief of the Giaka [sic] nation.”

To determine if the skull did indeed belong to Sandile, it was decided by his descendants and the traditional council to exhume his body. Anthropologists opened his grave near Stutterheim in the Eastern Cape. There, they found his skull, along with the rest of his skeleton.

Finding Nehanda’s grave and possibly exhuming her remains could finally solve the mystery, but the challenge facing Mahachi is where to look.

“We have these gaps in our history that we have difficulty filling in,” he says. “We have looked in a few places, but we haven’t come across records that point to a general area.”

One possible site is in the “native section” of the Pioneer cemetery. Harare’s oldest cemetery doesn’t lie too far from Nehanda’s statue that was erected in April.

“But this is,” sighs Mahachi, “an issue that is likely to occupy us for some time.” DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.