MATTERS OF OBSESSION

So you’re interested in video art?

Innately hard to grasp (and sometimes to watch), video art can feel intimidating and unapproachable. What is it all about, really?

Maybe you’ve been to a museum or gallery, sat down to watch the projection on the wall, and stared for fifteen minutes at images of red ants crawling over a set of rosary beads. Or two sets of projected hands scrubbing themselves clean, over and over, in an endless loop. Or several screens playing footage of over-saturated extremely close-up body parts mingling slowly with the anatomy of plants.

And maybe you – sitting there, gazing at this footage, a little uncomfortable — thought to yourself: what on Earth am I watching? What is going on?

For those interested in viewing and consuming contemporary (and modern) art, video art has become part and parcel of the genre. As Alina Cohen of Artsy wrote in 2019, “video art has become a requisite for any collecting modern and contemporary art institution”.

By its nature, however, video art is often slippery and obscure. The best of it can be difficult both to comprehend and to watch.

What is video art? And why is it different from film?

In the most obvious sense, video art is a genre that makes use of video technology as an audio-visual medium. But then, so do the movies. What is it that separates video art from cinematic art? And what separates it from the mass amounts of random clips, archival footage, snaps etc that float around the world today?

Most of the time, you will instinctually grasp that a piece of video art is not a regular movie. At the heart of the art form is a purposeful disregard for the conventions of traditional cinema making. Aspects like character development, plotline, comprehensive themes, and a narrative arc are not necessarily taken into consideration in the making of a video art piece.

Atmosphere at The Music Center And Dublab Present An Outdoor Art Installation Of Brian And Roger Enos’ ‘A Quiet Scene’ Video Collaboration at The Music Center Plaza on January 22, 2021 in Los Angeles, California. (Photo by Frazer Harrison/Getty Images)

In differentiating between video art and cinema, Rajendra Roy, the chief curator of film at New York’s Museum of Modern Art stated that, “the most practical difference between the two worlds has always been economic: unlimited multiples with audience-driven revenues [cinema] vs editioned copies”. That is to say, cinema is produced for the purpose of the enjoyment of the public, who pay to see the films. Video art, on the other hand, is not necessarily to be distributed or enjoyed widely. Video artists will display their work in a limited setting, usually in a gallery. The artist’s revenues are made from selling one or two exclusive pieces to a collector, museum or gallery.

Other differences include the fact that film is almost always a collaborative effort; a large team of people (actors, directors, editors etc) are generally involved in the production of a movie. Video art, on the other hand, can be (and is very often) created by one artist. Further, the quality of the video is less polished than that of film, which is part of its unconventional aesthetic.

That being said, video art can take a multitude of forms. Some critics separate the art form into two major categories: single channel and installation. The former consists of video footage displayed in a singular form, like a TV screen or projection. The content of the moving images itself is art. You could watch a single channel artwork by a video artist on your laptop at home.

Installation, on the other hand, consists of an environment where the video is used as part of a larger form. Perhaps there are multiple screens or projections, or maybe the video is a part of an assemblage or sculpture. It might also be used as part of a performance piece, projected behind or onto live-action. Many consider newer forms of contemporary art, like virtual reality pieces, video games or even apps as part of the video art genre.

As Chris Meigh-Andrews points out in his book, History of Video Art, “the form itself seems paradoxically to defy the activity of classification whilst simultaneously requiring it”. He argues later that the umbrella term video art is “often used as a way to describe and identify any moving image work presented within an art gallery”.

Visitors watch a video installation by Grada Kilomba titled “Illusions, Vol. II, Oedipus 2018” at the “We Don’t Need Another Hero” exhibition at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art during the 10th Berline Biennale on June 17, 2018 in Berlin, Germany. (Photo by Sean Gallup/Getty Images)

The history of video art

The genesis of video art is crucial to understanding what the art form is, and what it has come to mean.

Video art first entered the scene in the 1960s and ’70s, largely because of advances in video-making technology. Where earlier models of television cameras were expensive and heavy, the release of the Sony DV-2400 portapak in 1967 (and other similar handheld video-making devices) meant that recording and editing video was more accessible to the individual.

With video recording equipment being sold commercially, in a user-friendly format, experimental artists of the time had a new toy to play with. The form offered these artists a unique and compelling immediacy; real life could be recorded and played back right away. It was, in a sense, an audio-visual sketchbook ideal for an artist’s personal experimentation.

Wolf Vostell from Germany, and Nam June Paik, a Korean-American, are generally regarded as two of the first artists to delve into video as an art form. Both working across multiple fine art genres, these two pioneers brought an intertextual lens to their video-making practice.

Vostell and Paik were interested in the avant-garde music of composer John Cage, and the work of French artist Marcel Duchamp, both of whom influenced an art movement called Fluxus.

In simple terms, Fluxus is loosely defined as an international group of artists who were invested in debunking the art establishment and other cultural institutions. As Martha Schwendener from The New York Times puts it, “the idea of art [or life] as a game in which the artist reconfigures the rules is central to Fluxus”. She calls this “a perfect metaphor for the ’60s and early ’70s”.

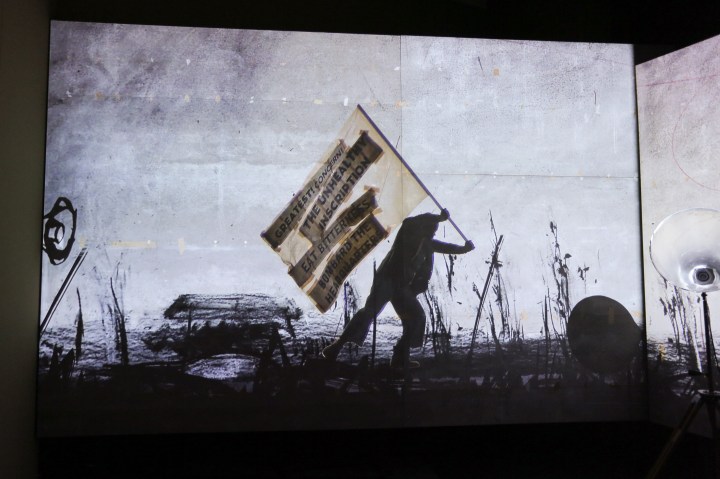

A general view of a video installation during the press preview of the exhibition ‘NO IT IS ! – William Kentridge’ at Martin Gropius Bau on May 11, 2016 in Berlin, Germany. (Photo by Christian Marquardt/Getty Images)

These ideas were key to Paik and Vostell’s work, and thus to the birth of video art. Video making as a medium of creative expression was cutting-edge; it had never been used as a tool before and did not have any of the formal burdens that came with more traditional forms of art like painting or sculpture. It was ripe for experimentation.

Further, American writer John Hanhardt wrote that video art stemmed, in part, from opposition to commercial television. In step with the anti-establishment notions of Fluxus, video art was in opposition to the easily consumable, mass-produced, and polished aesthetic of mainstream television.

With this in mind, it follows that video art as a form is more difficult to watch and understand than most cinema and TV. Unlike film, video art is not so much about telling a refined and interesting story (that sells), it’s about provoking thought and interrogating the medium itself.

Because video art served as a break from art history tradition, it aligned well with artists whose work attempted to critique political and social issues of the time. Many feminist artists used it as an entry point to dissect the male-dominated art world. Shigeko Kubota, a Japanese-American video artist (and wife of Nam June Paik), stated, “Video is Vengeance of Vagina. Video is Victory of Vagina”.

In a similar vein, artists like those involved in the Black Audio Film Collective used it to examine issues of class and race. Today’s video art continues to stay true to these primary concepts, despite the medium evolving rapidly with the development of new technologies. And while at its commencement, the art form was thought of as a marginal and inferior medium, it is now considered, says Meigh-Andrews, as “arguably the most influential medium in contemporary art”.

So what is the point of it? And why is it important?

Perhaps one of the most important things to point out about video art is the genre’s dependence on technology. As American author Marita Sturken explained, “the aesthetic changes in video, irrevocably tied to changes in its technology, consequently evolved at an equally accelerated pace”. Video art’s aesthetic and form remarks on the very technology that has enabled its existence.

It’s a cliché, but does life imitate art, or art imitate life? If we are living through the technological revolution, then, arguably, video art is the most accurate reflection of this moment in history in both its form and its multitudinous content.

If we are living in a surveillance culture (made all the more prevalent by the reality of social media) then video art embodies the blurry line between watching and being watched. If we are in a moment in time where our physical and digital lives are merging, then video art embodies the blurry line between the actual and the virtual.

To take it one step further, technology (and thus, video art) is innately ephemeral – it is difficult if not impossible to screen some earlier forms of video recordings. Technology used to create and replay them is out of date, or the installation of which they were a part has been taken down. Unlike a good/famous painting or sculpture, a piece of video art does not usually amass value as it gets older. Is that not a perfect reflection of the way that we consume information in our media-saturated today?

Compounded with its long-standing relationship with the avant-garde, video art’s “nowness” makes it a key proponent to understanding contemporary art, and thus, the world around us.

So how should we consume it?

There are two major things to keep in mind when watching video art. The first is that the experience is not meant to be easily or quickly consumed. Most video art is conceptual; it is designed to make you look closer or think deeper.

Which brings us to the second point, whereas most films are about storytelling and attempting to immerse viewers in another world separate from their own, video art as an experience happens in your own space. It generally makes you think about the moment that you are living through, whether that be the discomfort you feel looking at the screen/installation/virtual reality, or the historical moment. If we hark back to video making as a sort of audio-visual sketchbook for experimental artists, the art form is saying: these are some ideas, do with them what you will.

Some major names in video art (and their work)

In its amorphous and expansive nature, video art also has a huge (and ever-growing) range of practitioners. Listed below are a few big names – though keep in mind this list is not even scraping the surface of the art form.

Nam June Paik and Wolf Vostell are deemed to be the fathers of video art. Paik is perhaps most famous for his piece TV Buddha (1974), while Vostell’s first work was made in 1963 and named 6 TV Dé-coll/age.

Andy Warhol, the champion of the pop-art movement, was also known for his work in video. His extensive series, Screen Tests, was made in the mid-60s and consisted of a collection of over 400 silent black and white videos that featured stars of the New York downtown scene like Lou Reed, Nico, and Jane Holzer.

Making performance-based videos in the 1960s and 70s, Joan Jonas was a pioneer of feminist video art, conveying the multitudinous female identity through roles that she assumed on camera. Two of her works are Glass Puzzle (1973), and Double Lunar Dogs (1984).

Bruce Nauman, who has worked since the 196os, is renowned for his commentary (through video art) on surveillance. Contrapposto Studies, I through VII, (2015/16), is perhaps his most known work and part of the MoMA collection.

More recently, the seven-minute video essay titled Love Is the Message, The Message Is Death, work of Arthur Jafa has been added to the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and the High Museum of Art. It consists of a series of found images and video clips depicting black American experiences (generally violent footage) throughout history.

British artist, John Akomfrah was a founding member of the Black Audio Film Collective, and has continued his own successful video art career. Some of his critically acclaimed works include Vertigo Sea (2015) and Purple (2017.) His work often focuses on diaspora and migrant experience.

South African video artists and shows

Closer to home, South Africa boasts a thriving video art scene.

Perhaps the most well-known video artist in South Africa today is William Kentridge. His multi-channel video installation, More Sweetly Play the Dance (2017) was featured in the Zeitz MOCAA’s inaugural exhibition.

Penny Siopis is another central figure in South Africa’s video art scene. Her work, Shadow Shame Again (2021) was recently exhibited at Stevenson Gallery.

Other notable names include (but are by no means limited to) Nandipha Mntambo, Johan Thom, Gerard Marx, and Simon Gush (whose work will soon be displayed in an exhibition at the Stevenson Gallery in Johannesburg). DM/ML

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/8832″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.