AFRIKAANS LANGUAGE

An exhilarating linguistic minefield: Be duidelik and dala what you must

What’s up with Afrikaans? And why is Solidariteit meeting with the Thabo Mbeki Foundation for a Dakar-lite in leafy Newlands? From Settlement Dutch to Kaaps, the history of a language is unpacked.

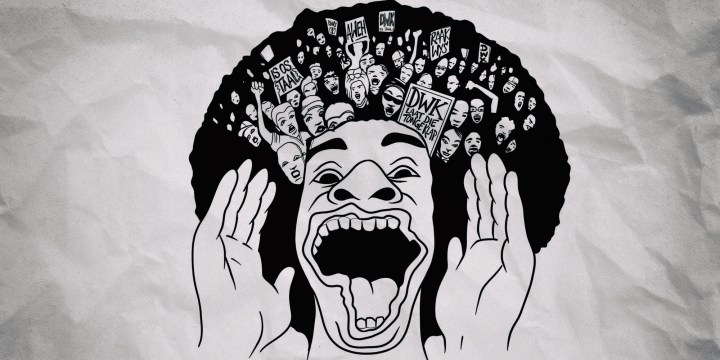

Calculating the precise lie of the land with regard to Afrikaans or Kaaps as a language, culture, political identity or even an economy, involves navigating an exhilarating minefield. It would mean listening to the voices of politicians, poets, bigots, cultural isolationists, business, historians, academics, language activists, journalists, political analysts and rappers.

It would mean hearing the claim for the language as a core of Camissa identity, which is how top cop and prize-winning author Jeremy Vearey describes his internal architecture. Vearey wrote his award-winning memoir, Jeremy Vannie Elsies entirely in lyrical, literary Kaaps.

Vearey – along with many other language activists, such as Willa Boesak, Quentin Williams, Adam Haupt, Rondela Kampfer, Nathan Trantaal, Ryan Pedro and Antjie Krog – nurture the indigenous roots of this widely spoken, vibrant language, one of the youngest in the world.

In this mother tongue, Table Mountain is “Hoerikwaggo” (mountain of the sea), and Cape Town is “Camissa” (place of sweet waters), the original Khoi name for the landscape.

The structure of the entire language is based on its Khoi origins and can be traced as far back as 1595 as a “market” tongue used to trade with passing Dutch ships. The arrival of slaves at the Cape in 1658 further contributed to its vocabulary and reach.

Wherever and whenever there has been a language debate in South Africa, Afrikaans is never far from the fray. In fact, it is usually slap bang in the centre of it all. It is a voorbok, so to speak.

Whether it is Minister of Higher Education Blade Nzimande’s proposal that Afrikaans no longer be considered an indigenous language, the EFF chanting “Down with Afrikaans”; whether it is about the language policy at tertiary institutions, or when it is used as a weapon of nationalism and populism, this stubborn, beautiful language continues to feature prominently in daily political and cultural discourse. (Not that most English-speakers have noticed, mind you.)

Not only that, the language sustains and drives a substantial chunk of the country’s cultural economy, with more books published and films made than in any other official indigenous language. There are four TV channels that churn out work 24/7.

Language policy at previously Afrikaans-medium universities has been a burning and divisive issue for over five years and a political football so inflated its seams are ripping apart.

On 23 September, the Constitutional Court ruled that a 2016 decision by Unisa to exclude Afrikaans as a language for teaching and learning had been unconstitutional and in violation of Section 29.

AfriForum, which brought the action through its attorney of record, Marjorie van Schalkwyk, said the ruling was not only “confirmation for Afrikaans as a language of teaching and learning but also all other languages”.

The most acrimonious debate about language policy has raged at Stellenbosch University, a bastion of Afrikaner identity and history. The decision by rector Wim de Villiers in 2016 that English be used as a language of instruction provoked howls of outrage and condemnation.

This “anglicisation” of Stellenbosch discriminated against Afrikaans-speakers, argues Boesak, a language activist, author, researcher and theologian. The biggest losers, she says, are “students from poor rural areas who have to grapple with being taught in a language that is not their mother tongue”.

Historian Herman Giliomee, writing in Rapport in May, labelled the decision “a fatal treason”. The decision, he said, was an economic one, meant to attract English-speaking students who could afford the fees while excluding brown, working-class students.

Williams, director of the centre for Multilingualism and Diversities Research (CMDR) at the University of the Western Cape (UWC), said that “any debate of Afrikaans at SU is immediately at best exclusionary, and at worst unhelpful to the magnificent future of Afrikaans”.

He said he had come to learn over the years in his field as a linguist that “no (socio)linguist at SU worth their scientific salt will touch the debate with a 10-foot pole”.

Many leading experts in language, identity, society and multilingualism in SA and across the world, he added, “either self-censor or privately bemoan the restrictions placed on their ability to teach and do research, given the oftentimes acerbic nature of debates surrounding Afrikaans”.

Giliomee said that, in the end, Afrikaans would merely be “a decoration” at SU, as French-Canadian academic and language expert Jean Laponce once predicted.

Responding to Nzimande’s proposal for Afrikaans not to be recognised as an indigenous language, literary icon Breyten Breytenbach penned a reply brimming with irritation.

“Go explain to Bram Fisher that he did not fight in Afrikaans, his indigenous and home-grown mother tongue, against the injustices of a humiliating regime.

“Go explain to Beyers Naude and Neville Alexander and Betsie du Toit and Abraham Viljoen and Jeremy Vearey and Dulcie September and Adam Small and Jan Rabie and all the other fighters against discrimination and the oppression of their language, the expression of their convictions and their connections to menswaardigheid (humanity) and their formative participation in an unacceptable reality, that the language that was forged from the melting pot of co-existence, from several origins from the African soil, is the fruit of our multiplicity and refinement, the language of the worker and the pagter (tenant) and farmer and the boss and the servant and the labourer and the activist and even sometimes the language of decision-makers, the only language on the continent that unashamedly and self-evidently names itself Afrikaans is not indigenous!” Breytenbach thundered. (Translated by this author from Afrikaans.)

Freedom Front MP and chief spokesperson for education Wynand Boshoff responded to Nzimande with a well-reasoned argument claiming that Afrikaans was unequivocally an indigenous language. “Afrikaans stems from a Dutch-based colloquial language of the 17th century, which was later referred to as Settlement Dutch,” he said.

“It comprises a simplified Dutch grammar and a Dutch vocabulary, which was further enriched by every language spoken in the VOC [Dutch East India Company] at the time. It was nobody’s mother tongue; it was simply a way to communicate about trade and industry across language barriers.”

Boshoff said the language later became the mother tongue of various language communities in the area that became South Africa. “Eastern Border Afrikaans is the historical variety that was mainly used by migrant farmers and, thus, moved inland; Cape Afrikaans developed in close vicinity to the Cape capital, where it was partially supplanted and strongly influenced by English after 1800; and Orange River Afrikaans was spoken by the descendants of the Khoi and San groups, after devastating smallpox epidemics disintegrated their original language communities.”

It was Eastern Border Afrikaans that had become the basis for “standard Afrikaans, as an official language”. The “non-indigenous” characteristics of this language were obvious, as were the “indigenous” characteristics, concluded Boshoff.

This statement provoked a diatribe from Leon Schrieber, DA head of elections for Stellenbosch, no less, who accused Boshoff of agreeing with the ANC and that his claims were “verbasend” (amazing).

Boshoff had written that “the fact that black people were not, and are still not, interested in being educated in Afrikaans is quite understandable”.

What was surprising, however, was the lack of interest “in being educated in their own mother tongues. Mother-tongue education for black children was the premise and main objective of the highly criticised ‘Bantu Education’. However, as soon as the black authorities gained control over it, it was replaced by English.”

Away from the Western Cape, where this debate finds its centrifugal force, however, are the lived experiences of black students at traditionally Afrikaans tertiary institutions, and which cannot be ignored.

When the EFF shouts “Down with Afrikaans”, it is a reference to the culture of these institutions, which are perceived to be unwelcoming and exclusive. These, too, are concerns that should not be overlooked.

In February 2021, a sort of Dakar-lite gathering occurred at the Vineyard Hotel in temperate Newlands, Cape Town – a meeting totally ignored by the English-language media. There, the Thabo Mbeki Foundation met with 12 Afrikaner organisations – the Afrikaner Africa Initiative, Solidarity movement, trade union Solidarity, AfrikanerBond, AfriForum, Federation of Afrikaans Cultural Associations, Dagbreek Trust, SA Academy for Science and the Arts, Business League, Freedom Foundation (Orania), Southern African Agri Initiative and National Employers Association of SA.

About 40 delegates spent two days in air-conditioned conference rooms to forge some sort of path between these Afrikaners, as they self-identified, and government.

That they met with the Thabo Mbeki Foundation rather than official government representatives speaks perhaps to the distance at present between the governing party and this constituency.

In the case of Kaaps, there has always been the mistaken notion that Kaaps is covered under the constitutional rights of Afrikaans as an official language. Yet, in recent decades, there has been an explicit acknowledgment of Kaaps and Kaaps-speakers as constituting one of the largest communities of Afrikaans-speakers in the Western Cape and elsewhere.

Afterwards, there was consensus that the country “was at a crossroads”, that many Afrikaners felt “alienated and excluded” and had “lost confidence” in the government.

A “statement” signed by 12 Afrikaner interest groups and the foundation agreed that 11 “priorities” needed to be addressed because these were “critical to the social cohesion and the economic development of South Africa and the African continent”.

They included the creation of “an inclusive economy”, a new financing model for emerging and existing farmers (black and white), identifying agricultural projects that could serve as “role models” for the rest of the country, as well as the promotion of “all indigenous languages in schools and other educational institutions”.

The signatories would begin by “tackling two important projects”: saving the Lovedale Press in Alice in the Eastern Cape and reviving the Groenberg school on Schalk Burger’s Wellington wine farm, Welbedacht.

The delegates called for the “greater inclusion of minorities” in politics and for Afrikaners to have access to “executive authority policymakers”, especially on issues raised at the hotelberaad.

Through the Thabo Mbeki Foundation, Afrikaners undertook to reach out “to other communities in South Africa and the rest of the continent to exploit the potential for cooperation and to promote ‘mutual recognition and respect’”. Afrikaners did not want to be “discriminated against” in education and were seeking a degree of “autonomy” to run private educational institutions.

Afrikaners should also be recognised and treated, they resolved, “as an African cultural community”. They sought “to be treated and recognised just like other traditional and cultural communities in South Africa”.

“The parties acknowledge that it will be impossible to build a country on foundations of mistrust. This is therefore a practical journey to develop trust between our people and our communities, and, more importantly, to work together to promote the spirit of vuk’uzunzele, independence, self-help and independence between our communities.”

The Solidarity Movement’s chairperson, Flip Buys, revealed a motto at the beraad: Ons sal self, ons sal saam (We will help ourselves, we will help others). “It must be a two-way relationship,” he declared.

Koos Malan, professor of public law at the university of Pretoria, afterwards wrote in Rapport that the importance of the 27 February joint statement should not be underestimated.

“It demonstrates the growing importance of community institutions amidst a vanishing state,” he said, adding that “here the state has deteriorated to such an extent that the existence of various forms of public order can only be ascribed to the efforts of well-organised community institutions and a self-regulating private sector”.

Political writer RW Johnson has described the Solidarity Movement (SM) as a “state within a state”. It “has spawned a whole series of related institutions, all resting on the Afrikaans tradition of self-help,” he wrote.

It boasted the involvement of 500,000 families in its work – a large proportion of the entire Afrikaans community. AfriForum, its “civil rights organisation”, had about 235,000 members, wrote Johnson.

Its “family institutions” included Maroela Media, “one of the largest press agencies in the country, providing free news”.

It also owns Pretoria FM; the FAK cultural organisation; the Sol-Tech vocational college; Solidarity Helping Hands; Solidarity’s university, Akademia; the Support Centre for Schools; the Study Fund Centre, which offers interest-free study loans; S-Leer, an adult education branch; Forum Films; Kanton Properties, a property investment company; as well as the Solidarity Legal Fund, Building Fund and History Fund. Also under Solidarity’s wide umbrella is Saai, an organisation of family farmers; Kraal Publishers; online school Wolkskool; and the Virseker, Campus and De Kock trusts, as well as various other associated institutions such as the Small Business Institute.

“This has been possible only because Solidarity has harnessed the enthusiasm and dedication of an entire community,” said Johnson.

He added that it was the most influential and capital-rich NGO in Africa.

For those who rightly remain suspicious of the potential for an Afrikaner nationalist revival, this might sound ominous and threatening. But it should perhaps be viewed within the fluid, vast context, dimensions and demographics of those who claim it as their mother tongue. They are as varied as the fruits on trees.

For veteran journalist Max du Preez, the question was whether the movement sought to “build a new sort of apartheid on the ruins of a stumbling democracy” or aimed “to nourish the dreams of all South Africans”.

Karen Meiring, the former channel head of kykNet, grew the channel into one of the most formidable and powerful platforms for the promotion and growth of Afrikaans – and also Kaaps.

The explosion of work in Kaaps can be directly linked to its exposure on these channels.

Meiring, too, has been the visionary force behind the thriving theatre, poetry and literary festivals that dot the calendar annually and that enjoy massive support.

There is an army of theatre directors, playwrights, actors, designers and musicians who have managed to build solid careers with the support of this language community.

These cultural and linguistic gathering points have also led to open, vociferous and challenging debates on a range of vital issues that seldom occur within communities that are exclusively English-speaking.

We give Williams the last word.

“In the case of Kaaps, there has always been the mistaken notion that Kaaps is covered under the constitutional rights of Afrikaans as an official language. Yet, in recent decades, there has been an explicit acknowledgment of Kaaps and Kaaps-speakers as constituting one of the largest communities of Afrikaans-speakers in the Western Cape and elsewhere.”

Kaaps was “finding an increasing presence” in higher education degree programmes, for example the Rhodes University MA creative writing programme and academic research and conference paper topics.

“And the frequent output of novels, novellas and works of poetry provides further evidence that Kaaps is not coextensive with Afrikaans but distinct from it.”

For any language to sing and survive the ages it needs to be spoken, sung and shouted from the proverbial rooftops.

Says Williams: “Reinventing Afrikaans in this sense would mean embracing our vulnerability in Afrikaans and confronting an enduring language fact: that in our not-so-new democracy, although an old idea of Afrikaans – as a language that inflicts symbolic and material pain – is dying out, a new and exciting idea of the Afrikaans speaker is emerging across the racial spectrum.

“This is a speaker invested in the ontological refashioning of their Afrikaans and its future.” DM168

Introduction to a linguistic love affair

Afrikaans and Kaaps are languages of flexibility and innovation that enable a fluent speaker to mould and shape them to their own tongue and circumstances.

Afrikaans is a language many of us were forced to learn in the 1960s and 1970s. It was used by those who claimed it as exclusively their own to control and direct the lives of others. It was a language the black majority rose up against.

It is a language that was gradually detached from its controversial and contested roots to grow expansive horizons and become one of the youngest in the world.

The first record of it dates from 1672, when it was inscribed by Khoi inhabitants of the Cape who had come into contact with Dutch traders. It is also spiced with Malaysian and Indonesian, spoken by slaves later brought to the Cape.

In 20 years from its official recognition as a language (and not just “slang Dutch”) in 1925, it grew to become a formidable language of literature and academia, of politics and religion, of resistance, oppression and rebellion.

The pioneering work of those today writing in Kaaps as well as the recent launch of a “descriptive corpus project that will develop the first dictionary” — guided by the Centre for Multilingualism and Diversities Research (CMDR) at the University of the Western Cape (UWC) — is a significant development in securing the future of the language and all its dialects, of which there are many.

Quentin Williams, director of the CMDR, at a Litnet University Seminar in March 2021 said that Kaaps, in decades to come, “will be seen, heard, read and used as a ‘language’ of teaching and learning in schools, universities, industry and communities the same way as standard Afrikaans”.

It is notable that it is UWC, a former “coloured bush university”, that is at the forefront of keeping the language buoyant and multilingualism alive.

Celebrated author, poet, intellectual, language activist and disruptor Anjie Krog’s pivotal role in pulling together intersecting circles of the language cannot be underestimated. She has tapped both the Dutch/Germanic roots of the language as well as being nourished by its indigenous Khoi and slave roots.

For many non-mother-tongue speakers, Afrikaans and Kaaps offer an alternative interior world as well as an entry to other languages including Flemish, Dutch and German.

In general, however, Afrikaans is a language in full flight, far from gasping any death throes.

The poems, the novels, the non-fiction, the biographies, the crime fiction, the documentaries, the reality TV shows, the series and serials, the films, the comedians, the advertising, the abundant bouquet of theatre and music festivals available to contemporary speakers provides ample evidence.

There are the cutting rhymes of rappers like Youngsta CPT and Jitsvinger, the blues of Piet Botha, the rock and indie alternative sounds of Spoegwolf, Gian Groen and Karen Zoid, the Ghoema, the Nederlandse and klopse liedjies, the soppy love songs, the epic narrations of Nataniël. There are the fine artists, the sculptors, the dancers, the chefs, the designers, the DJs and even the mega-boere. There are the newspapers, magazines and the political, literary and cultural websites.

This, and more, has added a richness to life in South Africa. I share something of my love and understanding of Afrikaans and Kaaps with the hope of encouraging more of us to gooi it every now and again. DM168

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper which is available for R25 at Pick n Pay, Exclusive Books and airport bookstores. For your nearest stockist, please click here.

Comments - Please login in order to comment.