OUR BURNING PLANET OP-ED

The hunt for Richards Bay minerals: Mines can bring development – but they also bring fear, resentment and violence to communities

The mine and various industries have contributed significantly to local economic development, but where there is money, there is also factionalism, corruption, violence and skirmishes for power.

Claire Martens is the senior communications officer at Natural Justice.

Richards Bay’s natural forests grow thickly among the rising chimneys of the smelters and factories. The dense, subtropical foliage, frequented by vervet monkeys and flocks of birds, competes with new industries, polluting mills and growing settlements. Beauty gives way to “progress”.

As we drive through the streets of the up-market suburb of Meerensee, our local guide points out the place where Nico Swart died in a hail of bullets. The general manager of Rio Tinto, of which Richards Bay Minerals (RBM) is a subsidiary, was gunned down in June this year – and while the reason he was targeted has been the subject of some media speculation, our guide says Swart was trying to stop corruption in tendering processes. He was “incorruptible”, according to one news story, and this is what cost him his life.

Along the shoreline, the dunes have experienced extensive storm damage. Crashing waves have exposed the multitude of mineral layers – the same minerals that are mined by RMB. The red, grey and tan layers hold the key to riches. The dune sand allows for the production of titanium dioxide, important for various consumer and textile goods.

At R8-billion a year, RBM is a major contributor to the economy of KwaZulu-Natal. The facility is tightly secured with a fence that looks strong enough for a prison yard. Cameras are dotted around at regular intervals. While our guide explains that the fencing is to stop vehicles and equipment from being stolen by staff, it does feel like the mine is also trying to keep people out. The area is, after all, fraught with tension, leading to RBM recently declaring a force majeure and closing its gates for three months following strikes and unrest.

The mine and various industries have contributed significantly to local economic development, but where there is money, there is also factionalism, corruption, violence and skirmishes for power. And assassinations.

A previous visit took us to the site where the byproduct of the mining processes is pumped into a black and desolate hole. This is where bodies are dumped.

If you own a smartphone, you are being tracked

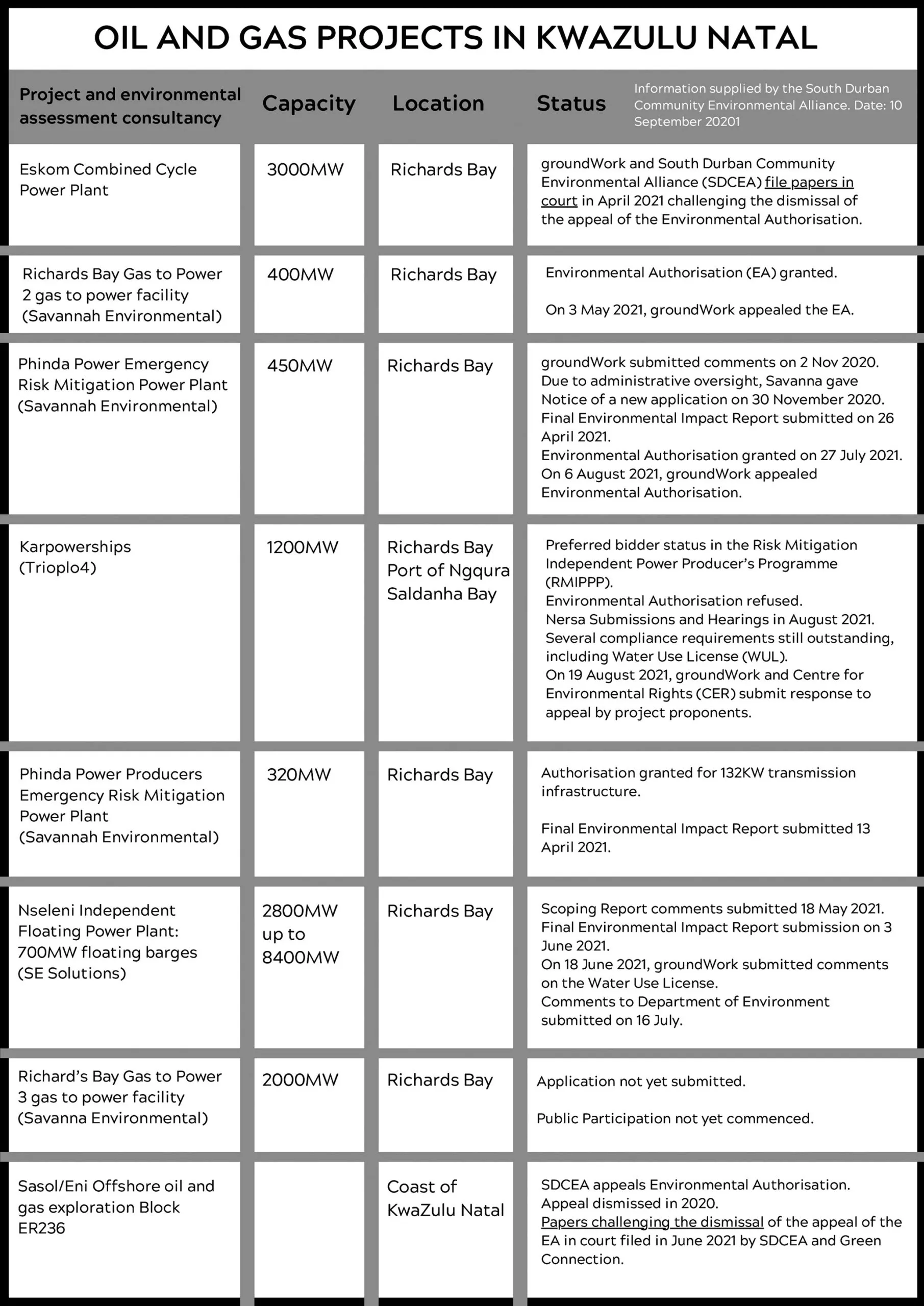

Our community meeting is small. Only a few people from towns surrounding Richards Bay have gathered to hear more about the Gas Power Plant, Eni and Sasol Offshore drilling and numerous other energy developments happening in the area (see the graph for more).

Richards Bay is not considered a “well-organised space”, in the words of activists. It is unclear how many people are opposed to new developments, especially considering the extent of the jobs created on the mines and within the industries. It is also unclear what the tribal tensions mean when it comes to support for development.

There are outstanding land claims amid deep-seated cultural norms and a strong respect for traditional authority. Together with a long history of political contestation and nationalism, activism in KwaZulu-Natal is often deeply contradictory and complex.

What is clear is that opposing certain developments, demanding accountability or speaking out against chiefs will get you into deep trouble – as can be seen by the recent developments around community trusts that RBM set up.

As Business Maverick’s Tim Cohen so aptly puts it: “I think it’s pretty clear that, if you put R130-million on the table, there is a pretty huge incentive to create havoc to get it – or to create havoc to ensure that other people don’t get it.”

Part of our meeting involved a briefing on security measures for physical and digital safety. The main message we wanted to get across, is that a network of support will be an activist’s best form of safety. However, two people approached me afterwards to tell me that they trust no one, not even their comrades. One says they only trust their family. The other says only their mother.

Anywhere in the world, owning a smartphone means that you can be tracked and surveilled at any time. In Richards Bay and surrounds, the risks are more extensive. No one is safe without a considerable amount of personal security – and even bodyguards are not enough. A local Richards Bay activist was killed in 2019 after a community meeting; one bodyguard was shot in the face, the other fled for his life.

When the community is divided, activists find themselves in a very dangerous position: they are not safe in their communities – but to do their activism, they need to stay.

Supporting activism when activism can cost you your life

For many nights since our Richards Bay visit, I have been thinking about security in KwaZulu-Natal. Assassinations are constant. As one journalist told me: “It is a bloodbath” – one news report estimates that approximately 30 activists have been killed in the province in the past three years.

One can draw a line between the violence wrought on communities and mining, infrastructure development and other extractive industries – Xolobeni, Marikana, Richards Bay. Developments create tensions and these tensions create violence. Developments are often reliant on government corruption to get the go-ahead – mostly without the knowledge or consent of the communities affected. Industries thrive on corruption in the system, and they are a source of corruption themselves.

South Africa is inherently and tragically violent and the victims are often communities, especially those who stand up or stand out.

The assassinations in KwaZulu-Natal – the rate and severity of them – are not unique in the world. A recent Global Witness report shows that 227 human rights defenders were killed in 2020; a third of the killings linked to resource extraction.

The question is: How do we help?

For the past two years, the organisation I work for has been administering a fund to assist activists in emergency situations. The requests are short term, but much thought has been given to longer term support. There are many forms in which this support can come.

For example, the provision of a small income for activists who have had their employment opportunities and family situations negatively impacted. Strong media reporting and international attention can also help, but not where the media are amongst those being silenced. We need courage in reporting.

What is important to understand is that individual activists do not work in a vacuum. It is vital to support individuals through supporting the communities they come from. This is where legal empowerment can be powerful.

Empowerment is a means of ensuring communities are deeply engaged in the Environmental Impact Assessment processes, are organised and educated, and understand the rights and responsibilities of parties involved, and can help to ensure that the much-needed participation and consent of communities is there from the beginning. If they care about compliance and want to avoid the long-term social and economic costs of corruption and community infighting, industries should be glad of such empowerment.

‘We don’t want to get rid of RBM, we just want them to do the right thing’

Communities in Richards Bay have certainly reaped the rewards of development. This is clear from the growing number of formal houses, busy small businesses and bustling schools. It is misguided to consider activists as anti-development. Rather, the communities I have met are all hungry for information but are often not seen as deserving or entitled to it.

I understand the confusion and anger of communities who are kept in the dark about what is happening in their area.

Very few industries have proven to be good neighbours to communities. In South Africa, we boast about our good environmental regulatory system, and yet there is a lack of proper implementation and transparency, which is what can lead to volatile situations such as those in Richards Bay.

For me, the solution is simple: transparency in the form of communication and information-sharing, and acting lawfully and in compliance with environmental authorisations.

It is the only way to build trust with communities – a more sustainable option for both parties. As one activist said: “We don’t want to get rid of RBM, we just want them to do the right thing.” DM/MC

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.