DM168 DEEP DIVE

Social media: The aftermath of #BringBackOurGirls

#BringBackOurGirls succeeded in focusing the world’s attention on a largely forgotten war and prompted Nigeria to recruit foreign mercenaries who helped turn the tide. But Nigerians who had been closely following the war watched as the frenzied international coverage also inspired a shift in Boko Haram’s tactics.

First published in the Daily Maverick 168 weekly newspaper.

You probably remember this story. But do you know what happened after you clicked “tweet”?

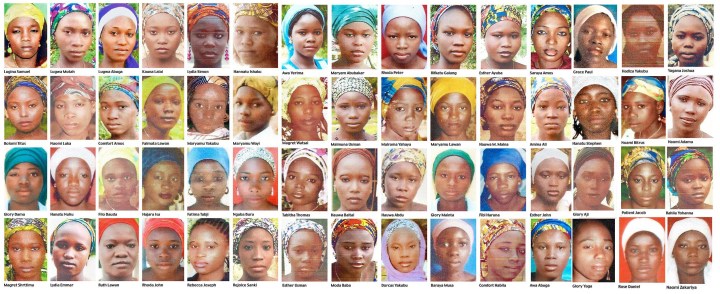

A class of high school seniors were in their dormitories in the sleepy northeast Nigerian town of Chibok on the evening of 14 April 2014 when a band of Boko Haram insurgents stormed into their boarding school and drove them at gunpoint into a remote forest.

For weeks barely anyone noticed, until the news hit an artery on social media, prompting some the world’s most recognizable people – Pope Francis, Kim Kardashian, The Rock, Michelle Obama – to fire off a hashtag that lit up billions of phones: #BringBackOurGirls.

The four words they rallied around became a clarion call that tested the power of social media to advance a cause thousands of miles away. The girls became a global priority. To free them, seven foreign nations dispatched billions of dollars in armed forces, drones, satellites and sophisticated surveillance equipment. Dozens of intelligence agents, hostage negotiators, psychosocial therapists and rescue teams set up office in Nigeria’s capital.

Then, seemingly just as quickly, Twitter’s hive mind swarmed onto its next viral cause, the #IceBucketChallenge, and never really returned.

And yet, away from public view, the real story of more than 200 schoolgirls’ years in Boko Haram captivity was just beginning. And those few days of viral tweets calling for their release lit a fuse that continues to burn until today.

The rescue mission launched in 2014 has quietly and covertly evolved into a military deployment across four west African countries. Nigeria’s military, US diplomats, and terrorism specialists still express bewilderment that a short-lived series of tweets so profoundly shaped the conflict with Boko Haram and other jihadist and bandit groups, which continue to kidnap children for fame, foot soldiers and ransom: more than 1,000 schoolchildren have been kidnapped in northern Nigeria since December.

For seven years, we have been reporting on the aftermath of a viral hashtag, a study on how our online actions can have seismic offline consequences for people continents away.

Through hundreds of interviews with officials involved in rescue efforts and 20 of the Chibok girls who were freed, we found a years-long trail of unintended outcomes that neither the advocates nor cynics who dismissed it as “slacktivism” could have foreseen. The lessons reverberate globally for democracies grappling with the unpredictable power of social media, and defy any easy conclusion.

#BringBackOurGirls succeeded in focusing the world’s attention on a largely forgotten war and prompted Nigeria to recruit foreign mercenaries who helped turn the tide.

But Nigerians who had been closely following the war watched as the frenzied international coverage also inspired a shift in Boko Haram’s tactics. Within months, the group was boasting that it had kidnapped vastly more young women, ransoming some and deploying others as its first female suicide bombers. “The hashtag unwittingly provided Boko Haram with a roadmap to use gender violence to further its global brand,” says Nigerian writer Tricia Adaobi Nwaubani, who has interviewed more than 200 of the Chibok families.

The course of Nigeria’s insurgency, which had been grinding to a stalemate, might have been different had the hashtag remained within Nigeria, where the movement began days after the 14 April kidnapping. But on 30 April, the hip-hop producer Russell Simmons, scrolling through his feed on a yacht off the French Antilles, became the first major US celebrity to tweet it, rallying American pop stars to resolve a Nigerian crisis.

Hours later, Twitter founder Jack Dorsey checked his phone during a dentist appointment to find hundreds of thousands of Americans joining this cause, crowd-sourcing the liberation of a high school class terrorised for their determination to learn.

“Extremely powerful,” he thought. “It touches every single person on the planet.”

Within days, the US’s most influential lawmakers, moved by a heartbreaking story that also satisfied the West’s faith in its own technology, gathered on the Capitol steps, calling for intervention.

From the White House Situation Room, officials held hour-long Chibok sessions to deploy more than a quarter of a billion dollars of sophisticated matériel over some of the world’s poorest farmland, looking for teenagers held by Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekau, a terrorist so unfamiliar to US intelligence analysts that they didn’t know which decade he was born in. Officials at the Pentagon were sceptical. “Why are we looking for some schoolgirls as opposed to looking for al-Qaeda?” one protested in a meeting.

But the hashtag presented the chance to dispatch military power against a group that had been reduced to a caricature of evil. The US sent Global Hawk drones and a 40-person team to Nigeria to staff a rescue mission, plus about 80 troops to the dictatorship of Chad. The British sent spy planes, while France and Israel offered intelligence assets.

Yet the world’s most sophisticated militaries had never embarked on a search mission like this, for 200 missing schoolgirls on whom there was almost no biographical information nor any social media footprint. From above, any aerial sighting of young women in the vast search zone of brown flatland streaked with dried riverbeds could just be ordinary village teenagers. Three months after the kidnapping, a surveillance photo landed on a bank of monitors in the CIA station in Abuja: about 80 young women in full-length mayafi veils sitting under a tamarind tree.

US and British officials studied it under magnifying glasses at an ambassador’s house. Proposals for a possible special-forces rescue did not materialise. It was hard enough under the best conditions to liberate so many hostages simultaneously. Worse, moving sufficient aircraft or armoured cars into the remote area risked being noticed by a bystander who might tweet the news and blow the operation. In other words, the intense global focus on whether the girls would be rescued was one reason why they couldn’t be.

“Everybody thinks, ‘Oh, you’re the United States, you can just fly some troopers in there and go in and rescue them,’” one US official supervising the effort said. “It’s not that simple.”

If the women weren’t going to be extracted by force, negotiations would have to prevail. Paradoxically, the hashtag had inspired all too many would-be intermediaries, as a bizarre cast of have-a-go heroes flew into the capital of Abuja, chasing fame. President Goodluck Jonathan’s administration, clobbered by the torrent of social-media demands, authorised countless competing negotiating efforts. All of them failed. When hostage talks and intervention broke down, the young women were forced to take survival into their own hands. As the months dragged into years, these students, most of them Christians, came of age in captivity. They began whispering prayers together at night, or keeping secret diaries, and copied passages about Mary from a smuggled Bible. At risk of beatings and torture, they softly sang gospel songs, fortifying each other with a hymn from Chibok: “We, the children of Israel, will not bow.”

Their hashtag fame spared them the worst treatment meted out to other captives, but also made it harder for them to escape from the many places they were held: forest camps and an abandoned mansion. When several of the students mounted a daring night-time escape, they were recognised by villagers who had seen them on TV, and handed back. Thereafter, only four successfully escaped, with 103 rescued by negotiation. More than 100 are still missing.

So how were the girls eventually freed? In a twist of 21st-century irony, the small team that ultimately answered the global demand to rescue the Chibok girls worked in secret for one of the world’s most discreet governments: Switzerland.

Their success relied not on expressing moral judgment, but suspending it, to reason with a group whose brutality was easier to condemn than to understand.

The men turned a second-floor embassy conference room into a makeshift classroom for the study of Boko Haram. They mapped its leadership structure, from its top decision-making body, the Shura Council, down through the qaids, or commanders, to the rijal, meaning foot soldiers. A whiteboard filled up with notes, near framed pictures of Alpine landscapes.

Their so-called Dialogue Facilitation Team mounted motorbikes into Boko Haram-held forests to deliver messages to contacts, hoping not to hear the whistle of an incoming air strike or a knock on a safe-house door. One of its members vanished into prison for two years, after meeting fugitives offering to pass information to senior commanders.

“The only reason these guys want to talk is because of Michelle Obama,” one of their first intermediaries said. There was fame in it. Yet that fame had paradoxically made the young women the insurgency’s most jealously guarded asset. “What the girls mean to Shekau is what 9/11 meant to Osama bin Laden,” another contact told them.

It wasn’t until 2016 that a deal came together: €3-million and five jailed Boko Haram fighters for those women who’d resisted endless pressure to join the group, with the students released in two batches. The first exchange would be a secret, all agreed.

But a bystander posted a photo of the young women as they went free, which went viral on social media. In retaliation, the insurgency delayed the second release by six months. In that time, at least two women, hungry after years of captivity, joined the group and have never been heard from since.

Those who were released received full scholarships to Nigeria’s now heavily guarded American University. Some joined a new debate club at which, one afternoon during their first year of freedom, the survivors argued both sides of a question they are uniquely positioned to answer: “Is social media a force for good?” DM168

Joe Parkinson and Drew Hinshaw are two of the Wall Street Journal’s most seasoned foreign correspondents and have won numerous international awards. Bring Back Our Girls is their first book.

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper which is available for R25 at Pick n Pay, Exclusive Books and airport bookstores. For your nearest stockist, please click here.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.