AFGHANISTAN & IRAQ WARS

Donald Rumsfeld’s legacy of ruin is nothing to celebrate

The passing of Donald Rumsfeld last week allows us to contemplate both his own life and works, as well as the baleful results of the two military adventures — Iraq and Afghanistan — for which he was the cheerleader.

If Donald H Rumsfeld had not re-entered government service in 2001, once he had entered the business world, following his first incarnation as the country’s secretary of defence, he might now be best remembered as a reasonably successful head of the outrageously difficult to manage, government mega-department, the department of defence.

His reputation would have been of a politically astute, supremely ambitious man who rose as an increasingly influential Washington figure during Republican presidencies prior to that (of whom Richard Nixon had endearingly called a “ruthless little bastard” on one of the White House tape recordings), as a supporter of some important legislation while he was in Congress, and as the very successful business leader he became later.

Along the way, Rumsfeld became the virtual Jedi master of the CYA memorandum. He perfected the art of despatching so many memoranda that he could, ex post facto, say he had been on the right side of virtually any position or issue. In his first time as secretary of defence, the flood of his memoranda in his first term as secretary of defence became known as the “yellow peril”. Then, in his second tour, the multitude of memos issuing from that desk where he worked all day, standing up, was seen to be like “snowflakes” in a snowstorm falling on the Pentagon offices and elsewhere as well.

But alas for Rumsfeld’s reputation, the temptation of another stint as secretary of defence came along when George W Bush won the presidency and as Rumsfeld’s longtime wingman, Dick Cheney, had become vice president. Rumsfeld accepted the position, and the twin disasters of the full-scale interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq he had helped make were the result. However, these did not just become calamities solely for him personally, but also for the US government, for the American people as a whole, and, of course, for so many thousands of Iraqis and Afghans as well.

Now, nearly two full decades after American troops began arriving in Afghanistan in their numbers, they are, nearly all of them, on their way back home from that Central Asian land. That country’s forbidding terrain and its fierce warrior traditions have sent yet another nation packing, yet again, without gaining the satisfaction of a favourable conclusion, after all that combat, blood, tears and treasure. Those must be accorded as tragic legacies from Donald Rumsfeld’s decisions.

Donald H Rumsfeld grew up in and around Chicago in rather ordinary middle-class circumstances, gained a partial academic scholarship for an education at Princeton University, and joining the Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps — NROTC — helped pay for the rest. Always combative, he starred on both his high school and university inter-scholastic wrestling teams.

NROTC and his graduation from Princeton led to military service as a Navy pilot, before returning to the Chicago area to run successfully for Congress for three terms in a reliably Republican district. But he was not an ideologically rigid conservative. While in Congress, he had helped lead the charge to unseat Republican minority leader Charles Halleck, seeing him as a man too rooted in rigid, past doctrine, to be replaced instead by a more politically moderate Michigan Congressman, Gerald Ford. While in Congress, Rumsfeld supported some civil rights legislation and he was a co-sponsor of the Freedom of Information Act.

In 1969 he joined the incoming Richard Nixon administration as head of the Office of Economic Opportunity. That agency was the administrative home for many of the Johnson administration’s earlier “war on poverty” programmes still continuing under the Nixon administration.

Throughout Rumsfeld’s rise during the Nixon and Gerald Ford administrations, his way stations became a counsellor to the president, head of the presidential cost of living council (at a time when inflation was a politically sensitive issue), US ambassador to Nato, then chief of staff to the president. When Gerald Ford replaced the disgraced Richard Nixon after the latter’s resignation, he appointed Rumsfeld secretary of defence. This came as the country (and especially the military) was still recoiling from the end of its disastrous misadventure in Vietnam and the military was in urgent need of rebuilding and repositioning.

One of Rumsfeld’s key initiatives was to attempt to trim a stressed military budget by cancelling several deeply over-budget weapons systems still under development. Another was an effort to push the military services to move towards more flexible command structures and units (in contrast to the more rigid structures in place during the Vietnam conflict).

Such reoriented organisational structures could respond more effectively to military challenges without the need to mobilise and deploy large units or engage over-complex, cumbersome command arrangements. Had these efforts been his legacy from heading the Pentagon, Rumsfeld might now be receiving rather high marks by defence analysts and historians for his time in office and his administrative and managerial strengths.

Following the Democrats’ return to power with Jimmy Carter’s victory, Rumsfeld moved on to academia and private industry, doing some university teaching and writing, then leading several corporations to improved profits and market share, including taking significant advantage of technological innovations in telecommunications. Along the way, using all his persuasive skills and government experience and connections, he gained federal government approval for the sale of the artificial sweetening agent, aspartame, better known as the brand name, Nutrasweet, from GD Searle, the company he was heading at the time. His business acumen and leadership skills also just happened to make him a wealthy man.

Then, when George W Bush was elected president in 2000, the temptation of serving in a leading role in the new Republican administration was something Rumsfeld was unable to refuse. He became the first person appointed to lead the Pentagon twice, becoming both the youngest and the oldest person to lead the massive department with all its civilian employees and, of course, the military.

With his passing, we can now see Rumsfeld as both a masterful bureaucratic actor and in-fighter (he reportedly outmanoeuvred Secretary of State Henry Kissinger on occasion during his time as secretary of defence and chief of staff in the White House), and then, later, after the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union, as a true believer in the triumphalist vision of America standing without equal, astride the globe. Lest we have forgotten, that was the worldview set out in books like Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History and The Last Man, and embraced by so many public figures at the time.

In that universe, the old Soviet Union was gone. China could be an irritant, but it was increasingly being brought into the global trading and manufacturing system, now that the excesses of the “Cultural Revolution” era were over. Moreover, Europe’s sometimes problematic circumstances were being tempered by the end of the Cold War and a sense of a pan-European future, and, with the exception of those never-ending ructions in the Middle East, the rest of the globe was either moving towards an acceptance of a post-Cold War world dynamic, or was of only modest importance to America.

There was, of course, one seriously discordant element in this picture, and that was Iraq and its resilient leader, Saddam Hussein. His forces had been roundly defeated militarily in the previous Bush administration by that forty-plus international coalition that had supplied forces and funds, but Saddam Hussein remained in power, in part because that coalition (and a previous president) had elected not to remove him from power.

Despite the US intelligence community’s unwillingness to confirm the actual presence of Iraqi nuclear or substantial chemical weapons development programmes, within the new administration, Rumsfeld and his former wingman and acolyte, and now vice president, Dick Cheney, became leading advocates of the belief in the reality of such gravely threatening projects. (Or, by less charitable interpretations, they chose to believe it — cherry-picking bits of unsubstantiated intelligence and the speculations of their favourite exiled Iraqi, Ahmed Chalabi — to provide a justification for military action against Iraq and its ruler.)

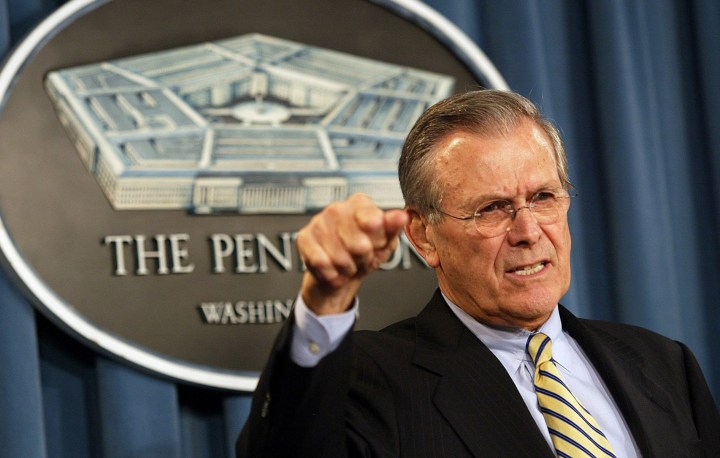

Former US Defence Secretary Donald Rumsfeld at a 2002 press conference in London. (Photo: EPA / Nicolas Asfouri)

Rumsfeld/Cheney, and those in their orbit, saw the presumed developments as the rationale to confront — then crush — the Iraqi regime militarily. Then the al-Qaeda attacks on the US on 11 September 2001 gave real impetus for attacking the terror group’s bases of operations in Afghanistan. This added weight to the Rumsfeld-Cheney position of hoping to deliver decisive blows on what they saw as Islamic extremism allied to a rogue state sponsoring terror acts and threatening to use weapons of mass destruction on others.

In response to the 9/11 attacks, military operations and then a build-up of US forces — along with those of other allied nations — in Afghanistan followed. But these forces were increasingly on a mission that morphed from pursuing and punishing al-Qaeda fighters to confronting and defeating its Taliban protectors throughout the nation.

The latter was in a conflict against an Afghan government installed after the departure of the Soviets, and that had been built on those Northern Alliance forces the US had previously aided in their struggle against the Soviet Union’s occupation and the government it had imposed on Afghanistan. (The US’s supply of Stinger missiles used to bring down Soviet Hind attack helicopters became a key weapon in that campaign.)

The ultimate failure of the Soviet intervention significantly contributed to the collapse of will of the Soviet Union, thereby leading to that putative end of history that was so warmly embraced by people like Rumsfeld.

With the more expansive Afghanistan campaign under way, courtesy of Rumsfeld and Cheney, and growing larger than its original task of crushing al-Qaeda’s forces, the US was now also revving up for a pre-emptive attack on Iraq, before those hypothesised weapons of mass destruction could be deployed against American allies in the region — and beyond. (But of course, the WMD were never discovered.)

Years later, American and allied forces would be in combat and combat support roles in both nations for what has seemed like forever. That is, until those forces have been drawn down from Afghanistan in an increasingly rapid race to meet President Joe Biden’s promise to be out of the country by 11 September 2021, save for a thousand or so posted to the vast US embassy compound in Kabul. Biden had never really been much of a supporter of the Afghan and Iraqi adventures from his time as vice president onward, and so this draw-down represents a logical culmination of his position. And, this decision, obviously, is something of a gamble looking forward.

The current unhappy circumstances of Iraq and Afghanistan and the two conflicts’ effects on America have now become a significant part of the legacy of Rumsfeld’s hubris. To that, we need to add fundamental misunderstandings about the actual nature of the two conflicts and societies that continue to reverberate in America’s approaches to the world and even domestic politics.

Now at Bagram Air Base, north of Kabul, the American personnel and much of its military materiel have disappeared. The handover to the Afghan government and its military of the base has been completed, and looters have already taken advantage of that moment to “liberate” laptops and other items easily carried away amid that transition. Until then, Bagram had been the busy core of the American engagement in Afghanistan.

Bagram had initially been a modest commercial airport built during the Cold War, back when the US and the Soviet Union had vied for influence and lavished foreign aid on the country. During the Soviet occupation, it became the core for their intervention and when the Soviets departed and as the American military entered the picture years later, Bagram became the centre of the American military intervention instead.

When presidents and other senior officials visited, their passenger jets made that characteristic corkscrew approach for landings to avoid ground fire and even the possibility of an unlucky ground-to-air missile strike by the Taliban. At its height, Bagram and surrounds was a military base city with housing for personnel, stores, dining halls, and many other facilities for the thousands of Americans and others who entered Afghanistan or left it as their tours of duty ended — as well as the inevitable departure of coffins bearing the remains of those who had died in the conflict.

American military sources are now saying air support for Afghan government forces will still be possible to some degree flying off an aircraft carrier stationed in the Indian Ocean or from US bases in the Persian Gulf region, but it will be much more limited than what had been possible out of Bagram. And after all the fighting, death, and the cost — all across the country, for all those years — a growing number of regional centres are either under the control of the Taliban or are being besieged by them. Accordingly, it is not at all clear the Afghan government will be able to hold off their opponents or reach a sustainable compromise for governing and rebuilding the nation.

As a people, Afghans are obviously no slouches when it comes to tenacious, skilful fighting, but for years, the government’s forces have become increasingly dependent on the logistical tail and hi-tech support supplied by the Americans. Whether they can now reorient themselves effectively to slug it out with their opponents the old-fashioned way (or have the fortitude to do so) is in doubt in the eyes of many observers.

In Iraq, a more stable central government now does exist; a semi-independent Kurdish polity exists in the north with American backing; but Iraq’s national government is now thoroughly aligned to its larger, more powerful neighbour, Iran. That surely is an outcome fundamentally counter to the intentions and desires of Rumsfeld and his tribe when they had launched their “splendid little war”, to borrow Teddy Roosevelt’s phrase.

Rumsfeld had infamously announced after the Iraqi invasion that he didn’t know precisely how long it would take to pacify the country, but he was sure it would be a matter of a few weeks at most. Wrong. The evolution of that war meant that it was not, in Rumsfeld’s infamous phrase, the known unknowns, that were a problem, but, rather, the totally unknown, unknowns that brought on so much of the mess. That and the deconstruction of the Iraqi army and much of its civil service by the conquerors without being clear what would come next.

Back at the beginning of the production of Daily Maverick, and in one of our early articles, we had examined the collapse of the American effort in Vietnam, with the sad histories of British and Soviet interventions in Afghanistan. And we hoped that we would not be writing about the withdrawal from Kabul by Americans in the same way in a few years’ time.

Yet over a decade later, it has come to the nearly total pullback by Americans as well. When our article was published back in 2010, we closed with the words of President Gerald Ford about the follies of such imperial delusions as the helos flew off the US embassy roof in Saigon. Perhaps it is best to let the late former president speak for himself. And so I wrote in 2010:

“Swing back for a moment to Saigon. President Gerald Ford, the man who authorised the evacuation later wrote in his own memoirs: ‘The passage of time has not dulled the ache of those days, the saddest of my public life. I pray that no future American president is ever faced with the grim options that confronted me as the military situation on the ground deteriorates … mediating between those who wanted an early exit and others who would go down with all flags flying … running a desperate race against the clock to rescue as many people as we could before enemy shelling destroyed airport runways… followed by the heartbreaking realisation that, as refugees streamed out onto those runways, we were left with only one alternative – a final evacuation by helicopter from the roof the US Embassy. We did the best we could; history will judge whether we could have done better.’ Indeed it will, and again.” DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Rumsfeld was a the core of the Bush administration’s cynical ploy to use the death of football hero, corporal Pat Tillman, from friendly fire in Afghanistan to their own advantage. They awarded him the silver star posthumously in order to make him a hero in spite of the fact that the only combatants on that fateful day were his fellow soldiers with not an enemy in sight.