YOUTH DAY

Counter contemplation: What the legacy of the June 16 Soweto uprising means today

The 45th anniversary of the June 16 Soweto uprising allows us to contemplate its larger meaning – through the eyes of some of those who were there back then.

When we look back at an event and recognise it as a pivotal moment, an inflection point in a nation’s history, beyond weighing what it has meant also raises a second question: Would things have turned out differently if the event in question had gone some other way?

For example, what would the shape of modern history have been like if 19-year-old student Gavrilo Princip had been a poor shot and failed to assassinate the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, while on a royal visit to Sarajevo?

There might never have been that grave Balkan crisis between Serbia and Austro-Hungary; quite possibly no World War 1 as nations followed each other into hostilities, and, if not that war, then most likely no World War 2.

Our world would likely have been immeasurably different with the continuation of all those European empires and their dominance around the globe – that is, unless you are one of those who believe in the implacable economic machinery of history.

Or consider American and world history if Confederate General Robert E Lee’s final gamble at the Battle of Gettysburg – with the charge by 10 thousand men across hundreds of meters of open ground, after two days of bitter fighting, in early July 1863 – instead of being decimated, had succeeded in shattering the solid line of Union soldiers holding the high ground and securely positioned behind a stone wall.

With General George Meade’s army smashed, the way would have been open for Lee and his army to capture America’s capital. With that, there would have been the collapse of any hopes for national reunification and, instead, the birth of an independent, slave-holding nation.

Given its own contentious past, South Africa also offers a wealth of historical events that fairly beg for the consideration of a counterfactual moment.

What would have happened if Pixley ka Seme and his colleagues’ pleas for a real political role for the African majority in the new South Africa, still being constructed, had been heeded?

Or what if Philip Kgosana had actually led his marchers right into the Parliament building to seize it in 1960, instead of agreeing to have his vast crowd disperse and that he should return later to present the demonstrators’ petition (whereupon he was promptly arrested)?

And a contemplation of counterfactuals must, of course, take us to a consideration of 16 June 1976.

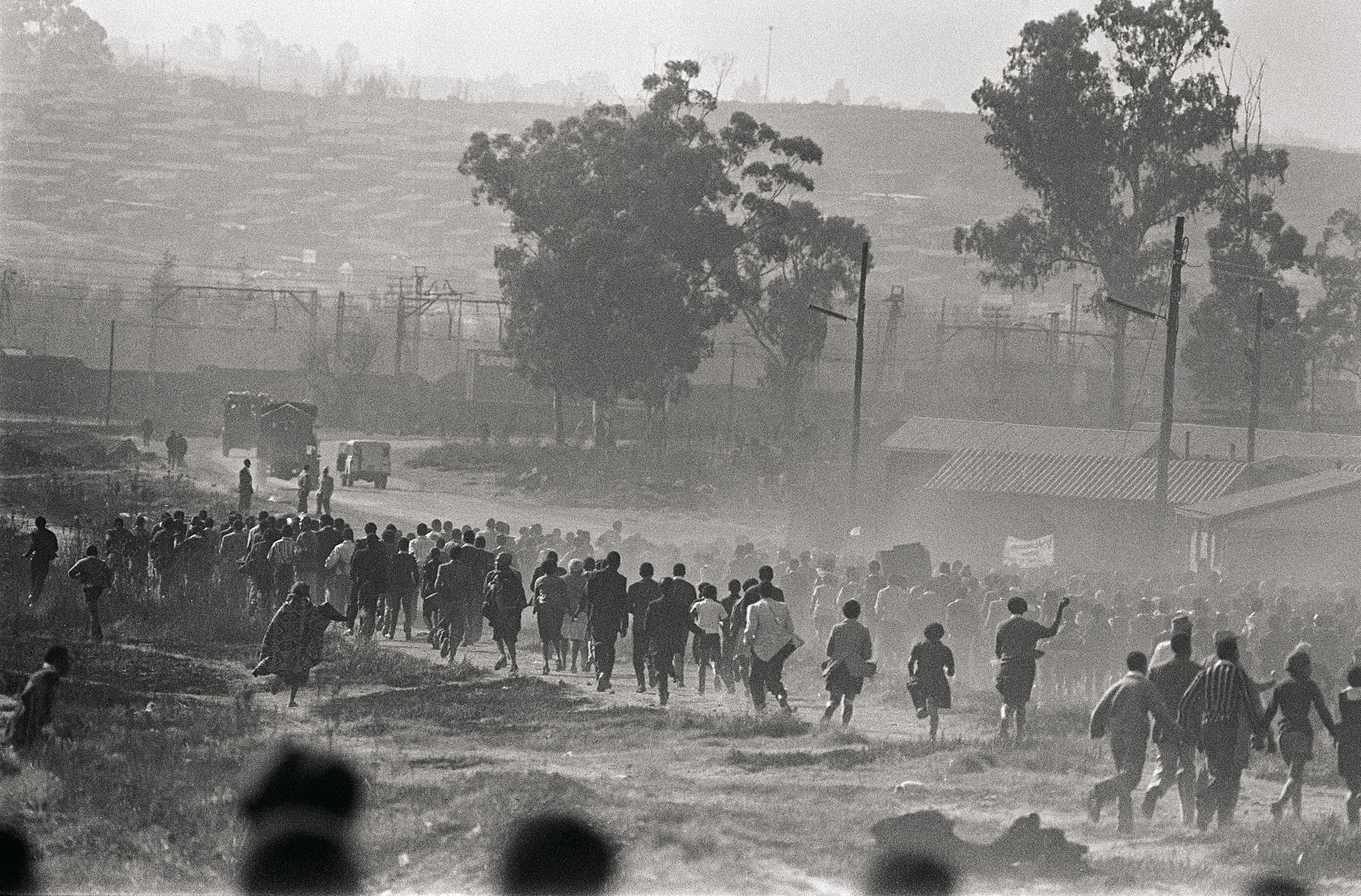

As most readers know, on 16 June 1976, a large march by students in Soweto was planned to protest against the apartheid government’s determination to implement an earlier decision to teach African high school students through both English and Afrikaans, with Afrikaans used as the medium of instruction in the sciences and mathematics.

The marchers wanted to reverse that decision for two reasons. The first was that they already had deeply negative feelings about that language inasmuch as it was the primary medium of communication used by those who had subjected the students and their families to lives of permanent, institutionalised political, social, legal and economic inferiority.

But there was also anger about this decision because there were very few teachers in African schools qualified to teach math and the sciences in Afrikaans. As a result, the students almost certainly would have had great difficulty in comprehending those lessons in that language.

Students themselves generally had so little command of Afrikaans that such a decision would mean they would be doomed to educational failure, should it become the reality of education in Soweto’s high schools.

The imposition of this rule thus seemed precisely designed to destroy what education was available under the harsh regimen of “Bantu education” – thereby dashing students’ hopes they could achieve the education needed for success in the modern economy, rather than being condemned to the pick-and-shovel work apartheid’s masters obviously intended for them.

The South African government in 1976 was at the peak of its seeming strength in controlling the nation and in stamping out efforts to thwart an increasingly all-encompassing system of apartheid. The earlier threats to its control in the early 1960s had been ruthlessly dealt with, and there were few if any organisations or individuals left to carry out successful public opposition to the government’s policies.

Internationally, while its most important trading partners were increasingly appalled by South Africa’s racial policies, they remained unwilling to pursue real efforts to ameliorate, let alone end, the apartheid system.

Although the substantial land barrier protecting South Africa’s northern flank, that had previously included the Portuguese colonies of Angola and Mozambique, had begun to crumble, with South West Africa still firmly in South African hands and Rhodesia holding its own against armed opposition to white rule, there was relatively little fear of any kind of substantive military-style infiltration by the regime’s opponents. Accordingly, the government was in no mood to negotiate over its domestic racial policies.

But on 16 June, instead of the government agreeing to discuss the students’ grievances – let alone making an announcement that the decision to roll out Afrikaans as the assigned medium of instruction would be subject to further discussion and consideration by a high-level commission to examine educational reform – the police were summoned and everything else that became the historical record for that day quickly followed.

Any possibilities of compromise, negotiation or conciliation evaporated. Instead, a continuing cycle of repression, killing and opposition took hold, and 16 June became the starting block for sustained opposition to apartheid and eventually the government itself.

This opposition finally culminated in the national compromises that brought an end to the old regime, in the face of a bloody stalemate that virtually promised to destroy the country.

But of that day itself, what was it like to be an observer or a participant to it all? Five years ago, in discussing these events in Daily Maverick, I wrote, “…this peaceful (albeit boisterous) students’ march was met with real police muscle and well over 100, perhaps as many as 200, students were killed on that day, and many more were wounded.

“Instead of the older Charterist ideals of the ANC, students at schools like Morris Isaacson High School had been increasingly affected by a new influence. Black Consciousness had exploded out of the segregated tertiary institutions like the University of the North and the University of Zululand.

“A growing number of Soweto’s younger, better-educated teachers were sympathetic to that intellectual movement or had been part of or strongly influenced by the concrete political expression of that ideology, the Black People’s Convention movement. They, in turn, inspired their high school charges with the idea that they must take charge of their own destinies and throw off the shackles of the racialised oppression now imposed on them.”

As a young, junior diplomat assigned to South Africa, one of my tasks was to try to understand more fully the growing sense of frustration and idealism. Making friends with some of those teachers and school principals, I regularly visited their schools, met their students and heard the arguments and complaints of teachers and students alike about their circumstances, rather than simply imbibing the Panglossian fantasy put about by government hacks.

One day I had an appointment, actually set for 16 June, to meet with a teacher – a science master at one of the high schools – who had recently been on an embassy-sponsored, month-long visit to the US. The point of our meeting was to review his trip in order to find out if the visit had met his expectations. Had there been any difficulties administratively, or in terms of the people he had met, or the places he had wished to visit? This was routine stuff.

As I wrote half a decade earlier, “…a few days before that scheduled meeting, the teacher had called to reschedule the appointment to a day or so earlier. The teacher apologised, but he explained that something else was now likely to come up on that day and he wouldn’t be free to talk over coffee or tea to review his trip. The appointment happened as planned.”

And so, instead of sitting in the staff common room of that Soweto school on 16 June, we were in our office, getting the early, censored reports of what was happening via the radio and, then, a bit more expansively in late editions of newspapers for sale on the streets. The story was that Soweto was the scene of a great march by students, and that a strong police presence had dealt with it.

In its report just a week after the march, the New York Times had reported, “The [earlier] language protest had been building, and there were boycotts in several schools. A week earlier a teacher was stabbed. A member of the Soweto Council, a black group, had warned two days before the riots that unless the authorities dealt quickly with the language issue, the protest could lead to violence.

“However, there was little awareness of the problem among the white South Africans whose newspapers hardly mentioned it. Certainly the governing white minority of 2.5 million did not view the Soweto protest as comparable to the organized campaign of burning identification cards that led to rioting in Sharpeville in 1960, in which 72 blacks were killed by police gunfire.”

For me, instead of meeting with our recent US visitor, that evening I was sitting at a kitchen table with a young surgeon from Soweto’s Baragwanath Hospital (well before the name Chris Hani had been appended to it). He slowly sipped a cup of coffee and spoke softly about his day, and this doctor demonstrated what battle-weary soldiers call “the thousand-yard stare” – the one where someone is beyond tears, anger or fear from what he has been through.

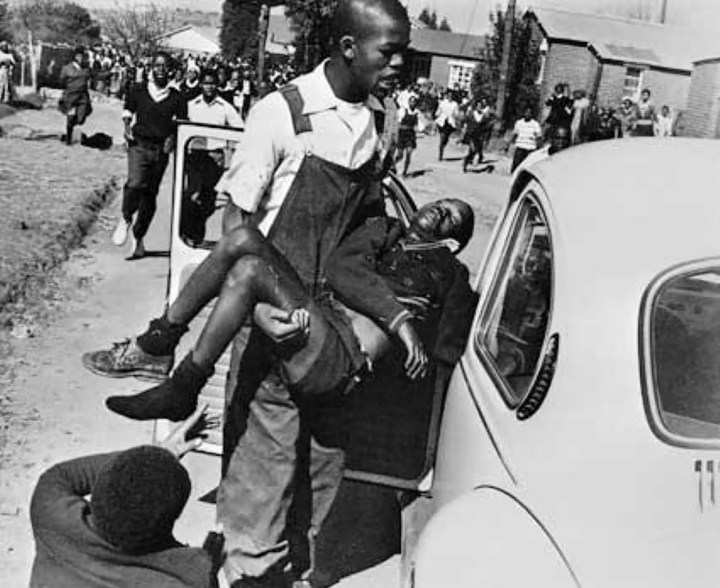

Pupils began to make their way to the various meeting points for a mass demonstration to protest against the use of Afrikaans in ‘black’ schools. (Photo: Alf Kumalo Family Trust)

As I wrote about it a half decade earlier, “It is the face seen on soldiers who have experienced so much combat in such a concentrated time period they can no longer process their memories. Instead of his usual routines of thoracic surgery and consultations with patients, the doctor had spent his afternoon in what had amounted to a field hospital, as the wounded were wheeled in with their grievous wounds from the police action against the students…. He explained that he couldn’t be sure of the exact number – he had lost count – but there had been hundreds brought into the hospital that day. And he had dealt with so many of them.”

The Times, in its report, had written, “In an account of the rioting later in the day, James T Kruger, Minister of Justice, said the police had exercised the ‘greatest measure of self-control’ and had fired only when their lives were endangered. He also said that the police had fired only after black mobs had hacked black and white government employees to death. However, it was not until nearly 11pm, three hours after witnesses reported the first police fire at the students, that the body of a black policeman was found in his car.

“On Friday. Mr. Kruger, at a news conference for the foreign press, said the march had caught the police by surprise. Three‐man patrols were dispatched to learn what was happening, he said, and 30 black policemen, only some of whom were armed, were sent with a white officer to head off the largest group of marchers.”

Further, according to the nearly contemporaneous account in the paper, “By the 18th the riots began spreading to other townships, and Prime Minister John Vorster, then preparing to leave for his meeting with Secretary of State Henry A. Kissinger in Germany, announced that the Government had given instructions to the police ‘to maintain law and order at all costs’.

“According to witnesses, the statement was followed by greater shows of force by the police, particularly in Alexandra Township, the only black area that is close to white residential neighborhoods. As the Soweto disorders were lessening, violence flared in townships northward to Pretoria, but it did not rage as long as in Soweto.

“The official death toll, which Thursday was reported as 140, was raised to 176 on Friday by the Minister of Justice. Mr. Kruger said the number included two whites and 12 children. He said 1,139 people had been wounded and 1,298 arrested.” Of course, we now know the toll was far higher.

From the vantage point of nearly half a century later, it is clear that what we call the “Soweto uprising” was a major inflection point in South Africa’s history. By the time the police had temporarily restored a semblance of control, it was already becoming clear nothing would be as it was again.

In the aftermath of that first day, I had also written that in the weeks and months after 16 June, “Hundreds of students fled the country and their black consciousness ideology was gradually superseded by the impact of the ANC in exile around Africa and beyond. Others remained inside the country, but increasingly they would become members of the various elements of the UDF: they would call for ‘liberation before education’, and they would become the foot soldiers and leaders of many other groups dedicated to regime change of apartheid South Africa.”

Now, of course, the legacy of the Soweto uprising has grown yet more complicated.

While the nation’s political system has, certainly, fundamentally changed, popular dissatisfaction with the circumstances of the present and the government’s general inability to provide basic services generates a growing litany of “service delivery” protests.

A new, angrier, putatively populist political party, the EFF, has emerged and there is a sense among many that the ANC has lost its way by virtue of its vast corruption and hyper-patronage politics.

More and more people ask themselves, is there another profound kind of political upheaval in the wind?

A decade after the original Soweto uprising, composer-dramatist Mbongeni Ngema crafted the musical, Sarafina, on the events leading up to 16 June. After great success at home, the show travelled abroad, becoming a long-running hit in New York City, among other stops.

As the students come together for their march into history, they sing:

And if I don’t live to see the day,

You better believe it,

I’ll be there.

This is my home and I’m here to stay

Freedom is coming tomorrow,

Get ready, mama, prepare,

Freedom is coming tomorrow,

Get ready, mama, prepare…

Perhaps South Africans are beginning to demonstrate again – in different ways this time – their claim for a fuller measure of freedom from what still ails the country’s polity and its economy.

A fuller contemplation of the larger meanings of 16 June may help remind people that freedom is not simply delineated by the right to mark one’s ballot every five years.

It also means calling an ineffectual government to account when they fail to meet the needs of a patient citizenry. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.