DM168 FEATURE

Sunday bloody Sunday: South Africa’s devastating and tragic secret massacre

A massacre in Duncan Village, East London, in 1952 claimed between 80 and 200 lives, many more than the 69 civilians shot dead by apartheid police eight years later in Sharpeville in 1960. Yet what happened on that Sunday, 9 November, is perhaps so ghastly that we have been too afraid to look deeply into this hidden massacre and confront its meaning and lessons.

First published in the Daily Maverick 168 weekly newspaper.

There is a lump of rock in the garden of the King Dominican nursing home in the town of Tralee, County Kerry, Ireland, shaped in the form of the dismembered corpse of Sister Aidan Quinlan, brutally murdered, set alight and consumed on Bloody Sunday, 9 November 1952.

It was a day when a spasm of violence convulsed through Duncan Village, East London.

A day that not only claimed Sister Aidan (her religious name) in the most gruesome fashion imaginable but also the lives of an estimated 80 to 200 residents shot dead by police in a four-hour indiscriminate shooting spree through the dusty streets of the densely populated shanty town.

On that day more than 600 people had gathered in Bantu Square to attend a rally by the recently established ANC Youth League, led by, among others, Alcott Skwenene “Skei” Gwentshe, a member of the Hot Shots band who had been orphaned during the 1921 Bulhoek massacre.

It was he who had organised that day’s meeting in Bantu Square, where police later opened fire, sparking waves of successive violence. While the official death toll was clocked as eight, many more were killed, their bodies quietly removed by families caught up in the fire and flames.

It was into this hell that the Irish-born Elsie Quinlan, Dr Quinlan or Sister Aidan, turned at around 5pm her heavy black Austin A40 into then Bantu Street, which ran through the shacklands of Tsolo section Duncan Village.

That day, another white person was also killed in Duncan Village. Insurance salesman Barend Vorster was beaten to death after being chased by an angry crowd about an hour after Sister Aidan was left to burn in the wreck of the Austin.

For all the horror and the death toll, Bloody Sunday, as events that unfolded on 9 November have come to be known, has remained a peripheral historical event in the national psyche.

It does not enjoy the same commemorative status as 21 March and 16 June or other significant post-democratic struggle dates.

Author Mignonne Breier spent seven years immersed in researching what she believes is a crucial missing chapter in South Africa’s past “and what was one of the most devastating massacres of the apartheid era”.

Sister Aidan, who was also a medical doctor, visits a beer hall. (Photo: Supplied)

The result is a literary archaeological dissection of the massacre titled Bloody Sunday: The Nun, the Defiance Campaign and South Africa’s Secret Massacre, which has just been published by Tafelberg.

Breier’s extraordinary book echoes the engaging historic forensic narrative oeuvre of scholar and writer Jacob Dlamini in works such as Askari, The Terrorist Album and Safari Nation: A Social History of the Kruger Park.

The author’s search for the essence of truth and what led to the brutal murder, burning and eating of Sister Aidan was her original historical entry point.

But the vista soon grew to include the traces of the nameless who also died in Duncan Village that day.

Sister Aidan, writes Breier, who grew up in the Eastern Cape, “has always been with me”.

And it was this ghost and its whispers that urged Breier back to the scene of the massacre, where the story “became much more”.

Scouring all available records of the time and the life of her main subject, including court transcripts (however rudimentary), letters, remembrances and other historical and official records, Breier has restored a semblance of wholeness to the horror and tragedy of Bloody Sunday and Sister Aidan herself.

Several artists have been brave enough to circle and confront the meaning of it all: Penny Siopis in 2011 with her film Communion, filmmaker Mxolisi Qebeyi in his documentary Dark Cloud, photographer David Goldblatt in his portrait of the marble memorial to Sister Aidan that stands at St Peter Claver Catholic Church, and scholar and writer Njabulo Ndebele in his 2012 tribute, Love and Politics: Sister Quinlan and the Future We Have Desired.

Ndebele delivered the tribute in Duncan Village at the 60th commemoration of her death, “an occasion to remember and reconcile with Sister Quinlan”.

“What we need so desperately at this time is our future. The terrible end of Sister Quinlan’s life in the streets of Duncan Village, a life we are here to recall and reflect upon, will also remind us, perhaps cruelly, of the past that has already made us,” said Ndebele.

Burnt remains of Sister Aidan’s car in which she was murdered, after a mob attack during protests in Duncan Village. (Photo: Supplied)

He reflected how the story of the tragedy of Bloody Sunday was one “about a strange chemistry, the chemistry of loving and killing, and loving again.

“It is about life, and death, and life again. Sister Quinlan loved. Sister Quinlan was killed, Sister Quinlan is being loved again. The story ends today when we declare our love for her. And when we declare our love for her, we might declare our love for ourselves.”

Breier has served, in a sense, to restore the body of Sister Aidan with this book while the nameless remain so mostly, but now with a better collective acknowledgment and understanding of their demise.

It is not as if Sister Aidan has completely disappeared from view.

In 2016 a memorial centre was opened at St Peter Claver Catholic Church. It was the idea of Duncan Village-born historian and devout Catholic Zuko Blauw.

At the opening Blauw told the local Daily Dispatch that “all that remained recognisable was part of her hand firmly holding onto a rosary, which for many signified that she had been praying at the time of her death”, he said.

A hall, two classrooms, a boardroom, a small library and a kitchen are embraced by Sister Aidan’s name. Blauw had been inspired to do something after walking the streets of Duncan Village and witnessing the desolation of the youth with “nothing constructive to do”.

In 2017, a group of young actors from the Duncan Village Gompo Arts Centre staged a play at the National Arts Festival in Makhanda looking at the events of 9 November.

The play was not only about Sister Aidan’s death, said the critics, but also the hardships and humiliation black people forced into townships suffered during the 1950s.

Exactly how ruthless and relentless is evidenced in historical records of the era.

Sister Aidan Quinlan. (Photo: Supplied)

From 1948, when the National Party won a decisive victory in a whites-only election, black residents of East London became increasingly burdened and harassed by the state with pass raids, and raids for lice or beer. There were curfews that community leaders urged should be defied.

“In predawn raids, policemen inspected the petticoats of women and, on finding a louse, the entire household was conveyed to a dipping tank, where heads were shaved, bodies sprayed and clothing boiled,” wrote Anne Mager and Gary Minkley in their 1990 paper Reaping the Whirlwind: the East London Riots of 1952.

The day 9 November 1952 was “Remembrance Day” for the white citizens of East London commemorating Commonwealth deaths in World Wars One and Two. It was a whites-only affair regardless of the number of black South Africans who served. No one invited the black ex-volunteers.

“Not even the families of the 27 men whose graves lay in East London cemeteries were listed in the records of the War Graves Commission,” writes Breier.

Five months earlier, on 15 June, the ANC had launched the Campaign of Defiance against Unjust Laws.

Alcott Skwenene ‘Skei” Gwentshe. (Photo:Supplied)

About 2,500 people had gathered to listen to acting ANC Cape leader, Dr James Njongwe, who called for volunteers to deliberately break the law by failing to carry passes and thus flood the city’s jails.

By 9 November more than 1,300 people had been arrested in East London. Across the country police clamped down on growing resistance, first in Port Elizabeth, then Johannesburg and Kimberley.

And then there was Gwentshe’s meeting in Bantu Square, a gathering fraught with backroom politics and tensions within the ANC itself.

But the thing that we most cannot bear to explore is what happened to the charred mortal remains of Sister Aidan, a matter that leaves Breier undaunted in the book as she attempts to make sense of what motivated some people to hack off bits of the nun’s body and flesh and consume her as she burnt inside her car.

“In all court proceedings arising out of her death, witnesses gave evidence of flesh being consumed, either on the day or near the scene of the crime or after, taken away and prepared for muthi,” writes Breier.

A young Joe Slovo, who represented the accused at an inspection in loco with court officials. (Photo: Supplied)

Of the rendering of Sister Aidan’s corpse – the lump of rock in the garden of the King Dominican nursing home in County Kerry – Breier writes that artist Billy Leen’s sculpture (as well as police photographs) “leave no doubt that her body was brutally hacked and dismembered.

“But they don’t resolve the question that haunts any account of the events of Bloody Sunday; what happened to the flesh and bone that were removed between the time that Sister Aidan was killed and the time the police removed her remains (about three hours later).”

These are the same questions, the author says, that drove the many court hearings that followed Sister Aidan’s death.

“None of them [is] easy to answer. No one admitted in court that they had anything to do with her death.”

Likewise, she writes, no policemen admitted to any wrongdoing.

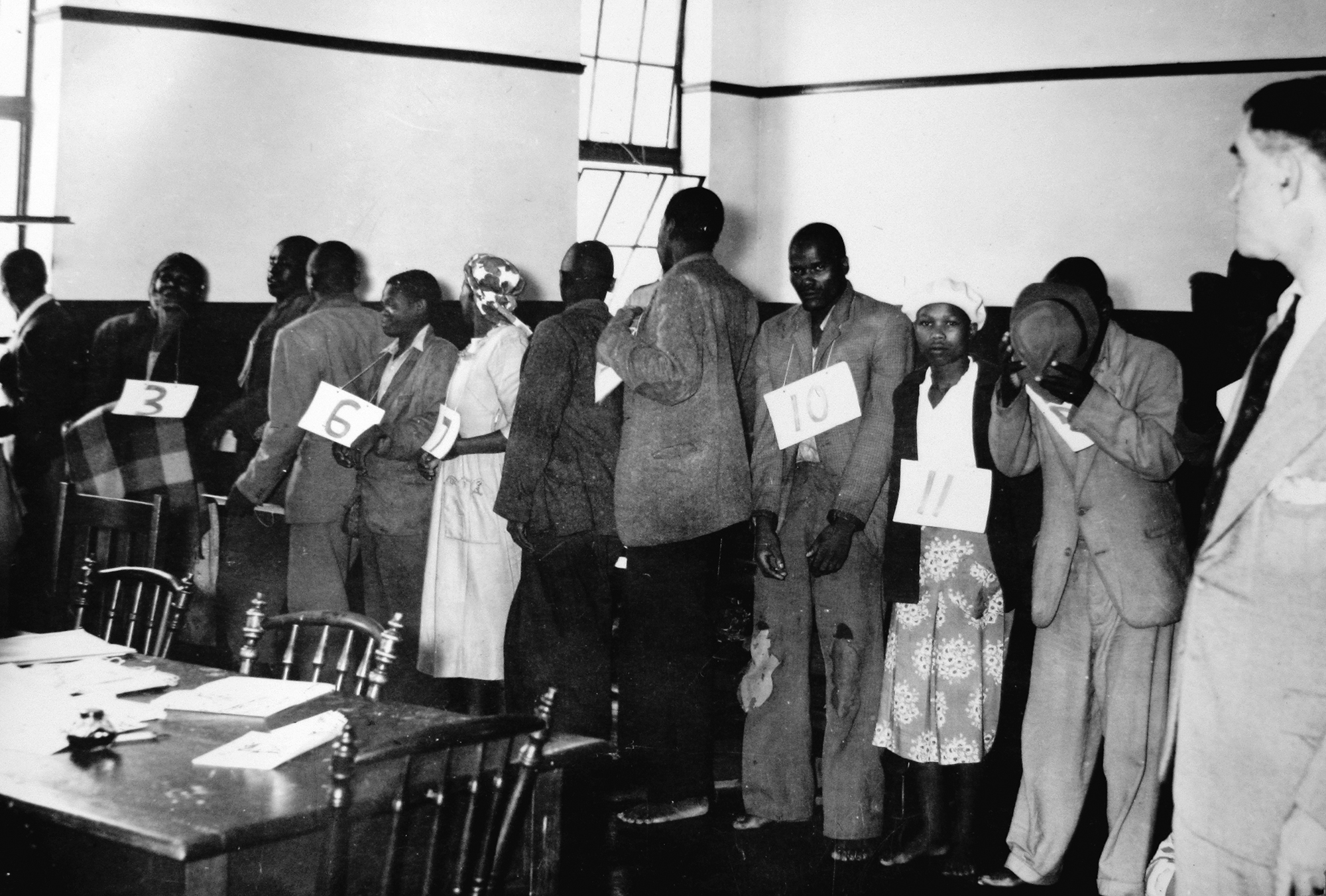

Breier writes how in the preparatory examination of the circumstances surrounding Sister Aidan’s death, 10 men and three women were brought before an East London magistrate.

The funeral of Sister Aidan was officiated by Father John. (Photo:Supplied)

At this hearing witnesses described the killing of Sister Aidan and what happened to her body afterwards.

In February 1953 the first allegations of “cannibalism” were published in the Daily Dispatch. The accused’s trials were separated, with eight facing a charge of murder and four a charge of “despoiling a dead body”.

Breier tracked the official record of the “despoilation” trial of Jackson Namase (25), Agnes Bewana (45), Tolwani July (21) and Ivy Plaatjies (30) in the Western Cape Archives, “but it contains only the bare facts; the pleas, adjournments, verdict and sentences”.

The four were found guilty and sentenced to six months and it was Magistrate JC Viljoen’s statement that “Not only have you done yourselves a great deal of harm, but you have also done a lot of harm to your race” that cut deep.

The assumption that the actions of a few who were part of an infuriated crowd who had been fired on by police and who responded with violence represented all black people is what shifted what happened that day into a spiritual and anthropological conundrum Breier is not afraid to explore.

Mxolisi Mhlekiswa, who was a young boy back in 1952 and who is now in his 80s, told Breier that Sister Aidan’s death “deeply hurt me”.

“I was aware that many people died, but my conscience is talking to me because … the work that she did spoke for itself, in school and at church. If you were looking for her they would tell you to look at the place where there are children, you would find her there, talking to children.”

Qebeyi, veteran political activist and director of Dark Cloud, drove one of the first initiatives to commemorate Sister Aidan.

Some of the accused at the trial. (Photo: Supplied)

As the 50th anniversary of her death approached in 2002 Qebeyi “had a vision for a project that would both atone for her death and have benefits for the people of Duncan Village”.

He produced a pamphlet, writes Breier, which suggested that if Sister Aidan had not been killed in the manner she had been, Duncan Village would not be in its “present sorry state”.

God, the ancestors and the township, said Qebeyi, had been cursed.

The “black cloud” generated by the burning of Sister Aidan’s car and her charred flesh “still hung over Duncan Village ‘like a pall of shame and despair’”.

Qebeyi managed to gain support from the Department of Arts and Culture for the commissioning of the memorial to appease both the Catholics and the ancestors.

That Sister Aidan was Catholic and that the Catholic missions have had such a lasting impact (positive and negative) in South Africa has much to do with the manner in which an interested reader might view the consumption of Sister Aidan after her death.

The Catholic faith is the only one that asserts that once a priest has blessed the Eucharist and the wine these actually become “the body and the blood of Christ”, which is then “consumed” by the congregation. This is known as transubstantiation, “the change of the whole substance of bread into the substance of the Body of Christ and the whole substance of wine into the Blood of Christ”.

The belief has been described by anthropologist Francis Nyamnjoh as “the cannibalism of transubstantiation”.

“In my view, Bloody Sunday calls out for further research to explore the way in which the sacraments, particularly the Eucharist, were taught by Christian missionaries and the ways in which they were taken up and reinterpreted in African communities such as Duncan Village,” says Breier.

(Graphic: Jocelyn Adamson)

She adds that, since the 1950s, revisionist scholars had turned Western accounts of cannibalism on their head, “querying the authenticity of the descriptions, the reliability of the data collected and the dearth of first-hand observations, describing them as one of the ways in which Westerners dehumanise the people whom they wish to colonise and thereby justify their own brutalities”.

The murder, mutilation and decapitation of Hintsa ka Khawuta by the British in 1835 is one such example Breier cites.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission too heard accounts of white policemen burning the flesh of activists while braaiing meat on fires and drinking beer.

On 14 November the Daily Dispatch reported on the funerals of seven of the eight people who died in the massacre and whom police admitted to killing. No names were mentioned.

Gwentshe, who organised the rally that day, died in 1966 after allegedly being poisoned by the Security police who detained him in 1964.

He is buried, writes Breier, in an overgrown cemetery off Douglas Smith Highway in Duncan Village.

As a leader of the ANCYL who had once rallied the second-highest number of volunteers in “the most important resistance campaign in the country’s history”, he has all but been forgotten.

As for the nameless dead, Breier writes that the Department of Native Affairs had stopped recording “African” deaths in June 1952. After 27 June 1952, the only deaths recorded were of “white and coloured people”.

“Where were the deaths of African people recorded after June 1952?”

These, the author learnt, were centralised in “Pretoria” and she realised, upon visiting the archive, “that the chances of finding any records of African deaths in East London in November 1952 were close to nil”.

“On the contrary, it confirmed that it was possible for a massacre to occur with no obligation on the part of the authorities to record who died.”

Sources in Duncan Village clocked the death toll as between 80 and 200, and while claims that far more people died that day have been reported sporadically over the years, these have not been investigated.

“The names of the black victims are presumed to be lost to history,” writes Breier.

Sister Aidan’s death, alongside those of the others, has kept us returning to the scene to make sense of it all so many years later.

Said Ndebele in 2012: “Interestingly, a state hostile to black people would have wanted to use the story of the killing of Sister Quinlan as an example of the depravity of black people, who killed one who loved them. But for some reason, the state seemed not to have done so, at least not in a concerted manner.”

The overall story of Sister Aidan’s “love for the people of Duncan Village” had accentuated her killing as “a tragic mistake”, noted Ndebele.

However, her death in the circumstances in which it occurred, he added, rendered Sister Aidan larger than the “mistake” and carried the potential “to be a transformative event for self-reflection by those who did the act putatively in the service of a larger cause”.

Breier’s tender and deeply researched book now adds to our greater understanding of a past with which we are still coming to terms. DM168

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper which is available for free to Pick n Pay Smart Shoppers at these Pick n Pay stores.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.