LOVE, UNSTOPPABLE

My dad, the pandemic and grief that comes from never saying goodbye

When he died in his wife’s loving arms, at the age of 78, my father broke his own promise to call me and make peace before his health deteriorated, so that we would be able to say goodbye.

In the very early hours of the Friday before Christmas 2020, my father died of Covid-19 complications.

I had no idea that he was unwell, and so even as my eldest half-sister’s number appeared on my phone, alarm bells started ringing in the midst of our annual family holiday in South Africa. I never imagined that it would be that final. That it would be her announcing his death, as she raced off the plane to Nice in France, to join our stepmother and half-brother.

Because I was so far away, in the middle of Mpumalanga, I wasn’t able to attend his funeral, which is probably the last chance to see the patchwork family of stepmother and half-siblings, our ties to one another unravelling with his death.

One of the only comforting things about my father’s passing was that his wife, my stepmother, was able to hold him in her arms until he passed, and that he was not alone. So many people have died alone, especially in the past year. It’s tragic – for the person and the loved ones – to know that they can’t even go and be next to their kin and let their grief, in a way, be metabolised.

I was the third of my father’s daughters. A very troubled and fraught relationship had estranged us for more than a decade. In better times, he had called me “favourite third daughter” as a term of endearment. In French, it carries the ambiguity of being the favourite third or the third favourite.

He had chosen my birthday, when I came along at the stroke of midnight, and the midwife asked my parents which day they preferred, for a child born at midnight needs determination. And he chose 29 over 28, because it is prime and more interesting.

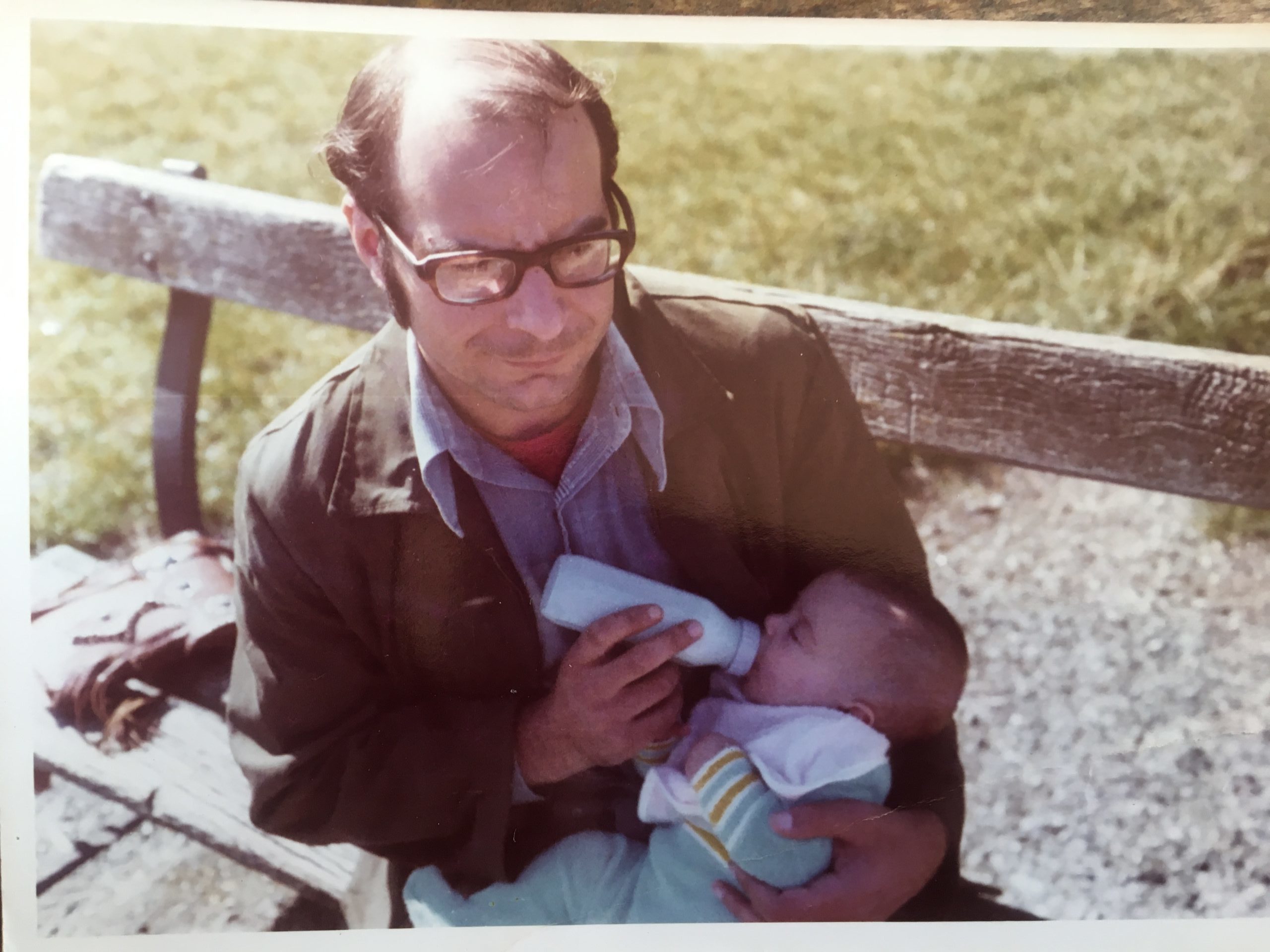

The author and her father. Picture supplied by Agnès Fiamma Papone.

The author and her father. Picture supplied by Agnès Fiamma Papone.

He was an inspirational and beloved mathematics teacher, and his love of numbers would colour every aspect of his life and many of mine. He inspired many vocations among engineers, doctors, veterinarians, who still laud him and credit him to this day for their professional achievements, part of his enduring legacy of teaching in Morocco, France, and later Côte d’Ivoire.

The difficulties of grieving the death of a loved one are insufferable at the best of times.

One of his many gifts to me in the course of his prolific intellectual life was a love of reading and a fount of book recommendations. Sometimes he could prescribe a book just as a doctor would prescribe a remedy, and it would be the perfect cure for whatever was ailing you.

When my maternal grandmother was dying, he’d suggested the beautiful Intimate Death by Marie de Hennezel, and it had been the ideal palliative. When I’d read it, I had never imagined that my father would leave me without being able to say goodbye. His father had been killed and left him without saying goodbye at the tender age of 12, at the outset of the Algerian war of independence. My father was taken from me by a virus, in far less dramatic circumstances, but it feels no less like the dogs of war were unleashed on us, his survivors, in our fight with grief and anger.

The difficulties of grieving the death of a loved one are insufferable at the best of times. But adding the layers of the current pandemic, the feeling of deaths being preventable, futile, ridiculous even…

Why couldn’t we flatten the curve like New Zealand, or Taiwan or South Korea? What’s so inept about all of us that we couldn’t just roll up our sleeves and get this epidemic over and done with? How much more regret will we have to bear that this unbearable loss we collectively suffer could have been prevented? Or is this just the inevitable denial phase of the five stages of grief?

Before my sister’s call on that fateful Saturday morning, I was very cautious about Covid-19, though not psychotic nor OCD. I have solid training in public health, and I am a fervent believer in vaccination, masks, hand washing, germ theory, sparing our elders and our health workers by adhering to social distancing, and contact tracing. Now that my experience of Covid-19 has moved from a level of abstraction to the intimacy of my own family, it has taken on a thoroughly different life. Unfairness. Futility. Anger. Grief again and again.

It appeared to me almost immediately that after this viral pandemic is over, once we eventually get it under control, that we will have another epidemic to contend with, an epidemic of sadness.

I think we need to tend to ourselves. We need to look after ourselves because grief just keeps adding on to more grief and it’s cumulative in effect. If you don’t look after it, it just gets worse like pulling open a scar or scratching off a scab. It won’t get better if we don’t look after it. As we give more voices to the process of this grieving, we open the floodgates for people to be allowed to grieve and add their voices to it.

For me, writing was the only way. I couldn’t talk, I couldn’t do anything. I sat up at night and I wrote because I just couldn’t do anything else, it was too painful.

My father and mother split up when I was nine months old, and I only saw him again when I was 10 and so I had a very episodic relationship with him. For the exceptional years that we did enjoy a warm and loving relationship, I am so extraordinarily grateful. When I had a father, he was the most loving and devoted. I don’t think he was a very parental father – in fact, one of his friends called him “the non-father” – but he was a very affectionate and loving person.

He used to tell me about how his father was a very fond stargazer who loved to sit outside on the stoep in Algeria and talk about constellations.

After Christmas in 2009 he never was in contact again. We had a falling out that I never understood, I never fully got the gist of it. I think that we got to be too close. All my life he’d been put on a pedestal for me. My mother wanted me to have a relationship of affection and respect with my father. Here we were now, finally so close – out of his four kids I was the nearest – and at the same time it was too near. My hindsight is that we got to be too close as unfamiliar people and the pedestal that we had each put up for each other started to crumble, the reality was too hard; to remarry the reality with what the image had been was too painful and difficult.

He just cut himself off and he never saw his grandchildren. One of the things that I feel most sorrowful about is that I had some intermittent opportunities to be my father’s daughter, but my children never had that with him.

He used to tell me about how his father was a very fond stargazer who loved to sit outside on the stoep in Algeria and talk about constellations. I really wanted my kids to have that with my father, and they never will. I’m not a very good stargazer and I think I chose not to become knowledgeable about that because it was my father’s domain. He was also a fierce card player. He loved and was extremely competitive about playing cards; bridge, whist, all kinds of high-stakes games.

After he died, for the first time, I played cards with my children, realising that I had subconsciously never played cards with them because it was something that I had associated with my dad. I thought to myself, it took my father dying for me to be able to play cards with my kids; maybe I’ll be able to stargaze with them now.

I have reams of the weekly letters he wrote to me as I moved around the world for my studies and my wanderlust. I happen to have gotten the news of his death just as I was about to collect the letters to finally take them back to France with me. I had left them in South Africa for safekeeping when I moved, and couldn’t face the task of sorting through them when he was no longer speaking to me.

Now the very thought of looking through them is unbearable, the grief too overwhelming, untenable. I will have to carry them home and read them much, much later in the future, when the devastation has abated and the pain subsided.

He turned 78 in August last year, and people tend to mark milestones like 80 because they’re nice, round figures and I thought that instead of waiting until he’s 80, I would send him a message. I wrote him a letter, which said: “Dear Papa, I’m sorry.”

That must have hit a chord because then, for the first time in many years, he replied and said: “I promise you that if my health deteriorates, I will contact you so that we can say goodbye.”

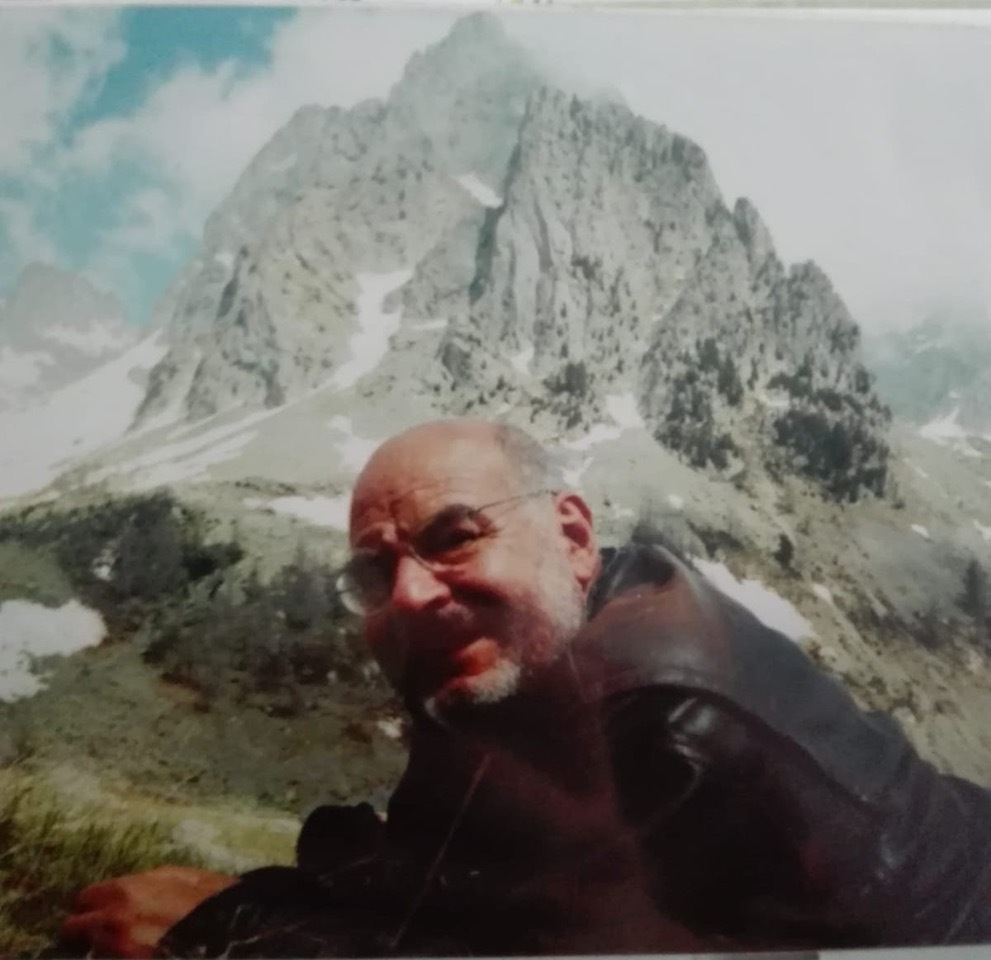

Papa. Picture supplied by Agnès Fiamma Papone.

Picture supplied by Agnès Fiamma Papone.

Here is the translated text that I sent to my niece to be spoken at my father’s funeral.

Papa

It’s your favourite third daughter

The only one of your children whose birthday you chose

A little after midnight so that it would be a prime number, the 29th of May.

I am once again too far away to return

It’s yet another time we will miss out

I am thinking of the best memories

When you told me I was a driving ace because I was driving very fast (like you), when we were on holiday together in Cape Town

When we celebrated my 30th altogether, at your place, like a tribe, with my 30 closest friends

When you wrote to me afterwards that you were so happy, so proud, that I was never ashamed of you

When you wrote the dedication in my Pléïade edition of Proust, that you had never imagined that the first Christmas we would spend together, I would be so many years old

Now we’re going to spend our first Christmas without you, when I had already lost you after a Christmas too many years ago

By the most unlikely of coincidences, tonight I am in Mpumalanga in the house where I had left all of your letters you’ve written to me since I was a little girl for safekeeping

I had kept them all so carefully [and entrusted them to Alex, one of my dearest friends, so that they would always be in a safe place]

It will be too painful to re-read them now, I won’t even manage to glance at them. I am going to take them all home, that was part of the reason for stopping here.

One day, they will be a source of sweet, fond memories, of joy.

Thankfully, there are really a great number of your letters, so the pleasure won’t be fleeting when the day finally comes.

Like you, I was in the habit of saving the best for last, like the nice runny egg yolk, we had debated about this at length.

The crusty bread for mopping up the meat juices left in the pan after having seared the meat.

Your recipe for veal cutlets in cream, with the shallots gently sautéed.

I think I am the child that missed you the most

One could imagine getting accustomed to missing someone

I never did

When I wrote you for your 78th birthday this year, you replied and you promised to call if your health deteriorated, so that we could say goodbye, like in Intimate Death that you had recommended to me so many years ago.

You didn’t manage.

You never managed to say goodbye to your own father.

Me neither.

I am grateful that you wrote it to me, it is far less sad to know that you had thought of it

I am going to try and tell you myself

Goodbye Papa. DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Thank you for sharing this beautiful and poignant relating of your grief and your struggle to come to terms with it, and the beautiful message to father. I think many of us are already caught up in a parallel pandemic of sadness, frustration, anger and a multitude of related emotions. Take care.