SPOTLIGHT

Hope in the Eastern Cape: A doctor reflects on the turnaround at Madwaleni Hospital

Vaccinations of health workers at Madwaleni Hospital in the rural Eastern Cape were set to start this week. However, steering this rural hospital to this point through a global pandemic had its challenges.

Speaking from Madwaleni District Hospital, Dr Andrew Miller’s voice falters. Despite the rural hospital staff’s best efforts, they simply did not have enough oxygen to save most Covid patients during the pandemic’s second wave. More often, healthcare workers were forced to turn to palliative care, cushioning death for the very ill. Nurses buckled under emotions, as, in this tight-knit community, patients were often family or friends.

The 180-bed hospital housed in a 1960 missionary building on a hilltop overlooking the Eastern Cape’s Xhora river, is two hours by rutted road from Mthatha. It services about 200,000 people, of whom only an estimated 70,000 are able to reach the facility.

Ferrying oxygen cylinders in bakkies

Miller relates how normally an Afrox truck would deliver oxygen at Madwaleni once every two weeks. But during the peak of the second wave, this amount of oxygen was required daily.

“What we started doing was sending the hospital bakkies to Mthatha to collect oxygen cylinders,” he says. “We’d send one or two bakkies every day, and they’d get loaded to the point where they were riding on their back wheels. So we had these drivers every morning, driving empty cylinders to Mthatha. Sometimes, by the time they were back, the oxygen was running out again. So they’d just jump in the bakkie and drive back.”

His eyes get wet when he speaks of staff sneaking in relatives to say goodbye to dying patients. He pauses, apologising for emotion flooding his voice.

“We had a lot more patients that we had to palliate, so we would just make them comfortable. It [meant] that we could offer really good care, even if it wasn’t life-saving care,” he says.

“And particularly with our compassionate nurses, you could do that. And it meant being a little naughty at times. Like, sometimes a low-risk family member would be snuck in to say goodbye…”

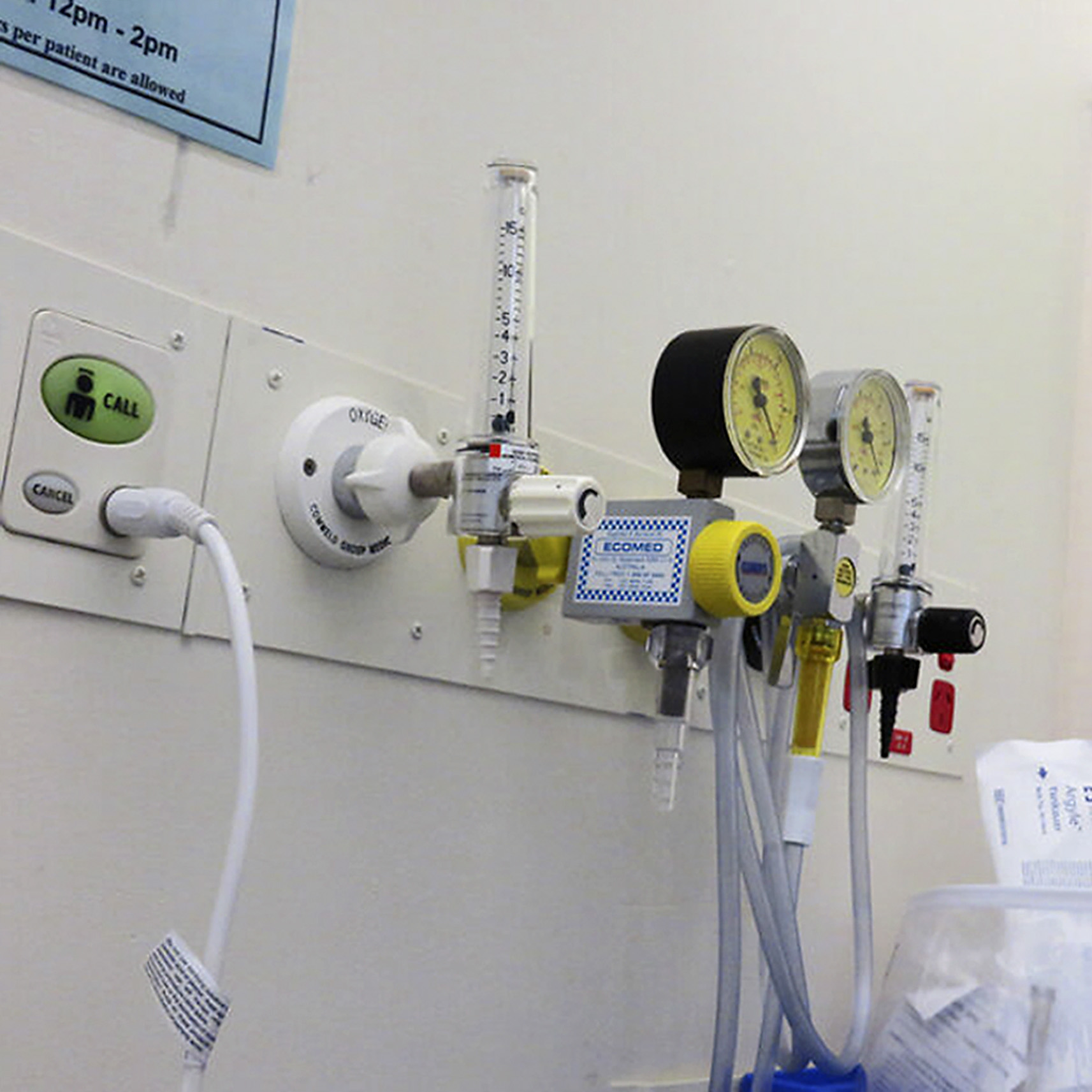

Medical oxygen outlets in a ward. (Photo: NewtownGrafitti / Flickr / Wikipedia)

Deaths tripling

Madwaleni’s Covid ward has 64 beds. During the second wave, up to two bodies were removed from the ward every day. Miller explains that they could not de-escalate other services like many urban hospitals did, as “everything we do is essential”.

“We couldn’t just stop delivering medication or stop admitting children, you know.”

He adds that Madwaleni’s deaths tripled during the second wave’s peak.

“Because we’re a rural hospital, we are used to elderly people being brought in to die because it’s difficult for families to deal with death at home when they’re so isolated. But what we weren’t used to was much younger patients coming in. You know, 50- and 40-year-olds were dying.”

Speaking over Zoom, Miller’s features often split into an easy grin. In his office, he is surrounded by stacked boxes. To his left, a bookshelf brims with ring-back folders.

Making a difference

In 2019, Miller (now 35) won the Rural Doctors’ Association of Southern Africa’s (RuDASA’s) rural doctor of the year award. Convenors of the annual award recall meeting Miller as an intern, at the time travelling around the Eastern Cape with his occupational therapist wife, Katy, looking for a hospital where they could make a difference.

He is credited as a focal point in turning Madwaleni Hospital around, which he inherited when it was in a state of collapse in 2013. At the time there was one exhausted doctor at the helm of the hospital, he recalls. Today Madwaleni has 14 doctors and a total staff complement of 380, including kitchen staff and cleaners.

Miller is thrilled that staff vaccinations will start this week.

“About two weeks ago we were finally told that we could get vaccinated in Mthatha but we would have to transport all of our staff there, all 380 people.” Miller said for him that was unacceptable.

“We couldn’t disrupt healthcare services to vaccinate staff, and it’s a risk to transport them, and it’s a lot of resources. So after engaging with the Sisonke trial, we got the go-ahead to start vaccinating here at Madwaleni on Thursday (April 15)*. In preparation, we’ve had to get a couple of extra fridges and so on.”

Dr Andrew and Katy Miller. (Photo: Supplied / Spotlight)

Managing a rural hospital

Miller is Madwaleni’s clinical manager, which means his time is split between clinical and managerial duties.

“So the idea is I spend time seeing patients, but also time working on systems and managing the hospital, which could mean anything from fixing a weed-eater to sorting out broken equipment, to recruiting new staff and making sure people are getting paid properly.

To support nurses during the second wave, one Madwaleni doctor arranged for pamper packs from the upmarket skincare range Africology.

“The nurses really struggled with those deaths,” says Miller. “So Africology packed these love packs for the nurses and, you know, we calculated, they were a couple of thousand rands per pack. We could give one to all of our nurses to say, ‘We appreciate you.’ Because the nurses felt that everyone was talking about healthcare workers in the cities, they were feeling forgotten.”

Miller’s optimism evidently goes rewarded. In 2019, the provincial Department of Health appointed a new hospital chief executive officer (CEO), Songezo Conjwa – the sixth CEO during Miller’s tenure. Miller describes Conjwa as a strategic and wise leader.

“It’s quite rare to find a good leader in a hospital like this. And so that’s been a significant turning point. We haven’t had walkouts, staff understood challenges we’ve had with PPE [personal protective equipment], you know, risks from Covid, and so on. I think that’s all been because of the CEO. He has these twice-monthly meetings with the unions proactively just to find out what issues they have. I mean, this is very different [from] what’s happening in Nelson Mandela Bay, for example. We’ve been very lucky to escape that.”

Pressing challenges

Meanwhile, medication procurement and reaching far-flung patients remain pressing rural healthcare challenges.

“Our referral hospital is Nelson Mandela Academic Hospital in Mthatha, which is two hours away,” says Miller.

“For example, we can’t transport newborn babies there over two hours. They don’t survive. So now we keep those babies. The solution was to expand our offering here at Madwaleni, which has been very rewarding. We’ve definitely found the Department of Health has responded positively to us wanting to do that.

“As for the medicine depot in Mthatha, it is unreliable. And yes, it’s very difficult to change something that you’re not a part of yourself. But we have two pharmacists who have been here for the last four years now, who are really good at hustling to get medication.

“You know, normally a pharmacist doesn’t spend their life trying to source medication, but these guys are really good at doing it. We do struggle, though. I mean, right now we have some essential antibiotics that are out of stock.”

Doctors visit two clinics in the area per day.

“So those clinics will be active about an hour away. We’ll use hospital transport, but most frequently the doctors just use their own vehicles because of challenges. The roads are really bad and their own cars are usually more able to cope with the terrain.”

In addition, the hospital has access to a helicopter used about every second week for emergency transfers to Mthatha.

“It’s quite a sight,” says Miller. “The helicopter lands on a field just opposite the maternity ward; there’s dust everywhere, dogs barking at its tail, with staff and patients going out to see.”

The sick often have to be transported in wheelbarrows to get medical help if ambulances do not arrive. (Photo: Black Star / Spotlight)

A hard life

Miller recalls his first day on the job when they saved a baby’s life after the mother suffered a cord prolapse (when an unborn baby’s umbilical cord slips through the cervix).

“So there was this group of incredible nurses that had been trying to keep the hospital going, with no maternity oversight from doctors,” he says. “They were just kind of trying their best, but they didn’t have the support. And even though they could have been quite bitter, as they’d been abandoned by doctors, they were very welcoming of us and very excited,” he recalls

“On our first day sitting in the CEO’s office, a midwife poked her head into the office and said to the CEO very softly that there’s been a cord prolapse, which is a maternity emergency. Then she walked out. The CEO wrote it down and then continued speaking to us. I looked across at one of the other new doctors, saying, ‘Did she say there’s a cord prolapse?’ So we ran down and found a woman that was delivering premature twins. We managed to deliver both of the babies, small babies. One of them lived, one of them didn’t live.”

Miller’s father also worked as a doctor in rural Eastern Cape. After completing a medical degree at the University of Cape Town, Miller hankered to return to the Wild Coast. Here he and Katy had two children, with one more on the way. Katy co-founded an NGO to support Madwaleni’s medical services. Among others, the NGO sources isiXhosa translators and runs a school on the premises for 30 children of hospital staff.

Miller cautions against romanticising the Eastern Cape’s postcard-pretty facade – the lush forests and hut-dotted hills.

“I think you should not romanticise this area. It’s a hard life for a lot of people here. I’m really privileged that I can come into a place like this and see beautiful hills rather than years of systemic oppression. And I think we’ve been very aware of that.” DM/MC

* Health Minister Dr Zweli Mkhize this week announced a temporary suspension of the use of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

This article was produced by Spotlight – health journalism in the public interest.

"Information pertaining to Covid-19, vaccines, how to control the spread of the virus and potential treatments is ever-changing. Under the South African Disaster Management Act Regulation 11(5)(c) it is prohibited to publish information through any medium with the intention to deceive people on government measures to address COVID-19. We are therefore disabling the comment section on this article in order to protect both the commenting member and ourselves from potential liability. Should you have additional information that you think we should know, please email [email protected]"