MAVERICK CITIZEN OP-ED

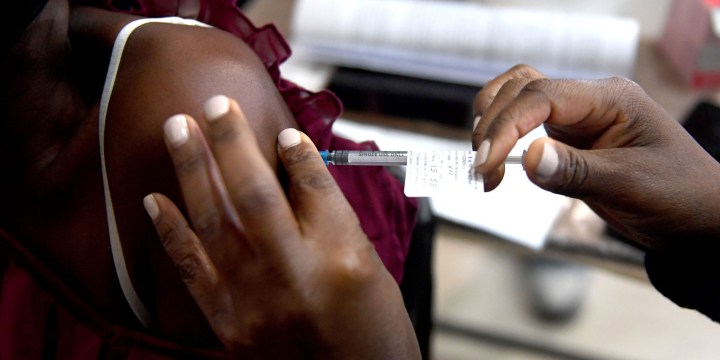

Vaccine roll-out: Age is the most important factor to prioritise in the queue

It is of course impossible to line everyone up exactly according to their risk relative to the person next to them, but if our aim is to curb death and severe disease, age will be by far the best proxy of risk until almost half the adult population has been vaccinated.

Once health workers in South Africa have been vaccinated against Covid-19, the focus will shift to the rest of the population. The Minister of Health has announced that enough vaccines should be available before the end of the year for all 41 million people in South Africa who are aged 18 years and older.

But the vaccines are not all going to arrive tomorrow, and even operating at full tilt, our combined public and private health services could probably only vaccinate a quarter of a million people per day; and while some people may be hesitant, I suspect that most of us would want to be near the front of the queue. That means that the government will have to prioritise the allocation of vaccines, based on what the programme is intended to achieve.

The first aim must be to reduce the incidence of severe infections leading to hospitalisation or death because this is the main factor forcing the government to implement the lockdowns that disrupt schools, workplaces and everyday life. If there were fewer serious cases and deaths from Covid-19, the country would be able to open up again. Our economy is on the ropes, there is no time to waste and this aim must be achieved in double-quick time.

Later — and I mean as early as 2022 — we hope to have vaccinated enough people to prevent new waves of infection so that this coronavirus becomes as manageable as the seasonal flu.

But first things first. In an ideal world, we would now line up every adult in South Africa in descending order of risk of severe Covid-19 disease and death. Assuming a social distance of 1.5 metres between every person, that queue would snake three times around the entire 20,000 km network of national roads.

With few exceptions, almost the entire first loop of that queue around the country — on the N1 to N18 — would consist of people aged 50 years or older, because they are far more likely to die from Covid-19 than younger people. The adjusted hazard ratio — that is the probability of Covid-related death attributable to a specific factor — for a healthy person 60 years or older is at least 10 times that of a healthy 40-year-old.

Certainly, comorbidities such as HIV, tuberculosis and severe obesity increase your chance of dying, but not nearly as much as advancing age. Its singular risk trumps that of most comorbidities right down to the age of about 45. The exception is poorly controlled diabetes, where the risk of death is similar to that of a 60-year-old. However, as with most comorbidities except for HIV, the more common form of diabetes tends to be found in older people, so that vaccinating everyone over 60 years of age would cover most diabetics as well.

It is of course impossible to line everyone up exactly according to their risk relative to the person next to them, but if our aim is to curb death and severe disease, age will be by far the best proxy of risk until almost half the adult population has been vaccinated. If delays in vaccine delivery were to necessitate further rationing, it would then make sense to target younger people with comorbidities as well as occupational groups that are potentially more exposed to the virus.

But if vaccine supply is not an issue later this year, the most pragmatic approach would be to keep heading south down the age curve.

There are special groups that will need to be treated differently because they are in places of institutional care where the risk of exposure is high. Similarly, outreach services to remote villages will be more cost-effective if the entire adult community is vaccinated on the same day. These exceptions can be accommodated in operational planning, but shouldn’t affect the basic age-based approach to prioritisation.

Similarly, in workplaces where employees can be vaccinated through occupational health services and where vaccines are available, there should be nothing to stop companies from proceeding as swiftly as possible down the age curve — trying to vaccinate every worker 40 years and older within the next six months. That would reduce absenteeism rates and contribute to the national reduction of death and disease.

What would not make sense would be for industry to choose to vaccinate younger employees first or ask for their employees to be pushed to the front of the rest of the queueing public. That would distort the basic epidemiological logic of the programme and lead to endless squabbles about who should receive special favours. Who would qualify as a worker — those employed or unemployed people as well; those in the formal sector or informal sector too? If everyone is included, what makes them any different from the rest of the general public who are required to wait their turn?

Attempting to accommodate these permutations would fly in the face of the imperatives of simplicity and speed and would be hard to justify from a point of fairness.

The primacy of age in the allocation of vaccines assumes that our immediate concern is to make Covid-19 a more benign disease. Once we achieve that aim and as studies throw greater light on the role of vaccines in reducing viral transmission — and whether the size of the effect varies by age — we may need to refine the criteria. Until then, it makes sense to follow the lead of countries like the United Kingdom, which has already vaccinated 95% of people 50 years and older and possibly even curbed new waves of infection by capitalising on the speed of rollout when age is the single factor that determines your place in the queue. DM/MC

David Harrison is the CEO of the DG Murray Trust. He is a medical doctor and specialist in public policy.

"Information pertaining to Covid-19, vaccines, how to control the spread of the virus and potential treatments is ever-changing. Under the South African Disaster Management Act Regulation 11(5)(c) it is prohibited to publish information through any medium with the intention to deceive people on government measures to address COVID-19. We are therefore disabling the comment section on this article in order to protect both the commenting member and ourselves from potential liability. Should you have additional information that you think we should know, please email [email protected]"

Become an Insider

Become an Insider