Maverick Citizen | Maverick Life

Theatre for whom? Dance for what? Towards a rationale for theatre and dance in our contemporary world

I believe our job is to be human because from the bottom we hold deep faith, we are resilient and passionate about bringing change to the world and we see the human spirit as more important than just building wealth — the true spirit of an artist.

This is an edited version of the keynote address Maqoma presented at the Take a STAND Dialogue, hosted by SU Woordfees and STAND Foundation in Stellenbosch on February 20, 2021.

This is a start of a weekend that I am certain will reveal possibilities and contradictions, a weekend that will bring us even closer as the artistic community; a weekend that will enrich us as we navigate and reflect on the past, the present and dreaming of a better future for our sector.

I’m deliberately using the word dream not as a metaphor but as real desire. Psychologists suggest that our dreams may be the mind’s way of alerting us to unresolved issues, while psychics argue that our dreams hold important clues about the future. African traditional healers say that our dreams are a connection to our ancestors.

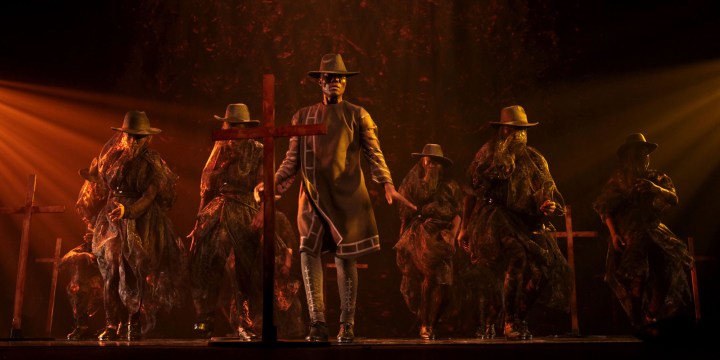

‘Cion: Requiem of Ravel’s Boléro’ choreographed by Gregory Maqoma in collaboration with the Market Theatre and inspired by Zakes Mda with choral score by Nhlanhla Mahlangu and Xolisiwe Bongwana. Costumes by Black Coffee’s Jacques van der Watt and performed by Vuyani Dance Company. (Photo: John Hogg)

I had the privilege of spending a day with the Great iSanusi, uBaba Credo Vusamazulu Mutwa in, 2019. He was ailing, in his bed and I sat next to him, he held my hand and spoke of Napoleon and the fundamental liberal policies he introduced in France and Western Europe.

That topic raised my curiosity and patience, as now and then he will take a nap and I will wait anxiously for the next brief moment of him talking. Much of that talk was about empires, how they will fall and how Africa has been resilient over time and that those holding power will be weakened by a revolution.

The days to follow were about understanding the conversation, trying to read between the lines. It took the impact of Covid-19 to fully understand the idea of a revolution and that for change to happen, a fundamental political will and courage needs to match the artistic power.

The topic tonight is asking: Theatre for whom? Dance for what? Towards a rationale for theatre and dance in our contemporary world. These are relevant, complicated questions that are challenging us as practitioners. I will try to answer these questions through the understanding of my identity and perhaps responding to a question which I always ask myself:

Why do I dance and for whom? Should they even care?

My calling

My calling is in dance, something I got to learn over the years when it was unconventional in many ways: firstly as a Black South African, brought up in the township of Soweto, secondly growing up with Christian values in a middle class family that looked at education as a major stepping stone to the promised land, the “Nirvana”, and thirdly as a practitioner.

When I introduce myself as a dancer, I mostly get a follow-on question — “so what else do you do?”

So why do I do this, why this urge to wake up every day, sometimes in the middle of the night, to dance?

I thought at some point maybe it’s my exposure to times before democracy that forced us to dance as a form of protest or maybe, just maybe, I have tapped so much into the right hemisphere of my brain which is all about the beautiful things, thinking in pictures, movement, the present moment, what I can touch and feel.

I thought of the world being such a perfect place, all living as brothers and sisters as beautiful creatures who are here to make the world a better place: I was wrong!

It was not the flair and the euphoria of the right hemisphere of my brain, it was something much deeper.

I realised this when I was on tour in Nigeria, in Lagos with Moving Into Dance as part of the African tour in 1996: I befriended a gentleman, a receptionist in a hotel that we were booked in. It’s a pity I did not record his name. I usually befriend receptionists as they are the ones who know the city best and in my young days of touring the first thing I will ask for is the nearest disco as if I was not dancing enough.

One evening after a performance we started to chat in general about life in Lagos, what is it like? He responded by telling me that it’s like most cities in Africa, the gap is so great between rich and poor. He continued to say “I’m just happy to be on the receiving end at the end of the month with my salary to take home to put some smile to my family, even though I know it is temporary.”

‘Exit/Exist’ concept and choreography by Gregory Maqoma and Vuyani Dance Theatre. Music performed by Complete — Bubele Mgele, Linda Thobela, Happy Motha and Bonginkosi Zulu with guitarist Giuliano Modarelli. (Photo: John Hogg / Dance Umbrella)

I took a good look at him and I said well my friend it takes time to discern any connection to life and work, to giving and taking, eventually you accept with a heavy heart that no man is equal, survival is only a word, living is what makes us be human irrespective of our circumstances.

My receptionist friend offered me coffee and said something I hold to heart to this day — “The city remains, it only changes in architecture, sometimes for the better but mostly for the worse because people don’t necessarily change, corruption makes the city a home for the bold, even when we pray and we forgive, still they eye the next deal — that is not living, that is impunity and by the time we wake up, the train has long left the station — that is life here my friend.”

I had to pause for a second to take it all in — he continued with a question directed to me: “So you dance? Why do you dance?”

For the first time I had to think deeply about my purpose, my gift and I could not come up with an answer. I mumbled something and before I could finish, he said to me “my friend you have a gift and a talent and that is your power. Power to make us see the world differently, to see ourselves through your dance and art and maybe even the stubborn ones may just give you attention, so use it!”

Then he quickly reminded me to drink my coffee as he turned his back to continue with his duties.

Power and art; power in art

Power, in our case as artists, is from a faithful personal vision of reality, and the reality facing the arts today.

We live in a country that is full of possibilities and contradictions. As artists we trade between these two words, possibility and contradiction, in our attempt to establish the basic human right and truth.

‘Exit/Exist’ concept and choreography by Gregory Maqoma and Vuyani Dance Theatre. Music performed by Complete — Bubele Mgele, Linda Thobela, Happy Motha and Bonginkosi Zulu with guitarist Giuliano Modarelli. (Photo: John Hogg / Dance Umbrella)

Power corrupts when it is misguided and controlled by fear, misguided power narrows our ability to serve with honesty — and when that happens, it provides a rationale for an artist to be critical because our concern for justice motivates us to stand for what we believe is right. That right is not based on assumption but a concrete tangible reality that there is a notion for history to repeat itself and at times with far more devastating repercussions.

I grew up next to a hostel, which housed migrant workers who came from different parts of Southern Africa. Over the weekends they will compete amongst themselves in very organised traditional choreographies and group formations. History and memory reminds us that the past is not dead, and I always think of the image of men living in hostels in the vicinity of my home in Orlando East, Soweto.

I think about how their dance was a way for them to remember home beyond the euphoria it is producing when I was watching their sweat dripping down their developed muscle-bound bodies. Dance for the hostel migrant workers was a deliberate psychic survival, a deliberate silencing of the harrowing voices of those they have left behind and those they may never see again.

Their dance was connecting their stories of displacement to the story of a place they can’t recognise temporarily. It is a story of a man digging deep down in the belly of the earth searching for gold they will never own. What they own is their name, a passbook and a death sentence.

The migrant workers were able to shake the ground with their powerful stamping but were unable to shake the economic will, simply denied but allowed to work the land with sweat, tears and life.

In similar fashion to the apartheid government’s style of kill and rule, like the 1960 Sharpeville massacre, was the Marikana Massacre on 16 August 2012. The South African Police Service (SAPS) under then Minister of Police Nathi Mthethwa, opened fire on a crowd of striking mine workers of Marikana, in the North West Province. The police killed 34 mineworkers, and left 78 seriously injured; 250 of the miners were arrested and their families left destitute.

That is often the price of democracy.

Gregory Maqoma. (Photo: Marijke Willems)

The image in colour, like that one of a man in a green blanket, remains the symbol of injustices. The name of the man in the green blanket is Mgcineni Noki, aged 30, and known to his family and friends as Mambush. Mgcineni stood as leader and shield, he took 14 bullets to his face and body.

South Africa prides itself in hills and mountains that stretch for miles, culminating in a landscape that resonates with people’s strength and resilience. Mgcineni addressed his fellow miners at a ‘koppie’, a rocky hill in Marikana. When Nelson Mandela was released and earmarked to be the first South African Democratic President, he was supported through the tripartite alliance: the ANC; the Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu); and the South African Communist Party. The action of rebellion by Mgcineni and his compatriots was spitting at the alliance and those in power in the unions, owners of mines as well as the senior police officers who unleashed a massacre that could have been avoided. Power corrupts, and too much power often yields political power that lies between life and death.

So who are we?

The We is in Me, is in all of us.

The We is the manifestation of an ideology of self with clarity, perhaps with complications of the unknown without admiration or biased pitiful, overzealous attempts to understand why the ‘We’ becomes political in our attempt to make theatre. With political consciousness we become aware of who we are and some knowledge of self and place creates a possibility for a discourse.

When I reflect and try to make meaning in my attempt to find reason to dance, to find words to describe the movement aesthetic my body exudes, the only word I can come up with is “architecture”: the landscape that continues to evolve and change, closely related to the earth and affected by its deteriorating nature. A collection of identities, acknowledging the many centuries of social and political heritage.

Every performance creates new, transitional entry and exit points. Every performance becomes a memory and when the lights go off and the curtain falls, a new history is written.

With this understanding I was inspired to create a formal aesthetic which became a bit of a cocktail: It is not the ‘bloody Mary’, nor the ‘pina colada’ which I sometimes get to enjoy because they have such cool names: my cocktail is about purpose and requires empathy to prevail over years and years of undeniable virtual landscape of dissolution that has given rise to a catharsis of universal grief conquering the sadness; the hard reality that continues to permeate the living confronted by death, rejection and poverty.

My dance carries in its fibre a human connection and attempts to name the nameless, like the Africans who perished during World War 1 who went to fight a war that was not their own.

So much ground has been denied, both figuratively and realistically, even when structures are in place to make it work, the cracks just grow wider.

As an artist living in the binary of what is real and denied, I question the existence of living in this chaos, with realities so unbearable, I choose to override and escape by dancing, my body being one with itself, a moment where I care less about my country — at least the portion that doesn’t care about me.

So yes I do ask, dance for what?

We are standing on unstable ground, the free market of democracy where I dance to forget with a hope that I will come out of the experience with a renewed energy, but only to be hit back to a coma, back to my reality of a place I wish to call home.

As I dance in isolation with my body, confined, tumbling in space and bouncing from wall to wall and pieces of furniture pulled and pushed to corners in my own home, I become a force of movement and a centrepiece. I become a single being separate from the energy flow that is usually around me in a form of other dancing bodies and souls.

This time I am one with myself, touching my soul, being one with over a trillion particles that make up my being. I discover the spiritual realm and I lull myself to the comfort of it as I drift deeper into the magical world. My movement goes beyond the euphoria, the beauty of the universe with its ugly skeleton.

And still I realise there is a Me in me and this dance which has no name, no beginning, no end, where I am not the choreographer, gives me strength to lean towards the tragedy and grieve with it as I try to understand the real life in the world of living.

In many places in the world, people feel that political pressure defines cultural identity in ethnic terms, and cultural diversity in political terms. Cultural identity, however, cannot be defined in terms of race and ethnicity alone. It is a complex subject that is complicated further by such factors as gender, class, generation, sexual and religious orientation and the tension between modernity and tradition.

The body becomes the temple that preciously archives these complexities and they become visible when a concrete force compels the body to rapture, to release a new matrix of conceptualisation and consequently of reproducing its own existence.

Many artists are doing this, they use their body to reconstruct the past, willingly or by force. I would like to believe that is the case, and that the approach is valid for the artists at that particular time, where the What? Who? Why? becomes the rapture.

In conclusion, my long-time collaborator and dear friend Nhlanhla Mahlangu found a poetic way of expressing “The real life in the world of leaving” in my 2004 work ‘Somehow Delightful’, where I was reflecting on the 10 years of democracy and asking myself what has really changed? I commissioned him to connect the expressions of the people to their landscape with their own stories of displacement and he said:

“The only thing I know

The only thing my eyes can see

The only thing my nose can smell,

The only thing my tongue can taste

The real life in the world leaving

I’m not talking about Cinderella

I’m not talking about Snow White and the seven dwarfs

I’m not talking about Harry Potter and the philosophers

I’m not talking about a prince who saved his princess from death by a special kiss

I’m talking about the only thing I know

The real life in the world of leaving

I’m talking about a place where oceans stomachs are filled with hunger until they close to bursting

Mountains cry tears of blood for their horizons who are hanged and burned for their infinity.

That is what I am talking about… the real life in the world of leaving.” DM/MC

Gregory Vuyani Maqoma became interested in dance in the late 1980s as a means to escape the political tensions growing in his place of birth, Soweto. He started his formal dance training in 1990 at Moving Into Dance, where in 2002 he became the Associate Artistic Director. Maqoma has established himself as an internationally renowned dancer, choreographer, teacher and director. He founded Vuyani Dance Theatre (VDT) in 1999. In 2019 Maqoma Collaborated with Idris Elba and Kwame Kwei-Armah in the production “Tree” produced by Manchester International Festival and the Young Vic. In 2020 Maqoma was honoured by the International Theatre Institute in partnership with UNESCO to be the author of the prestigious International Dance Day Message. Maqoma is the current chairperson of Sustaining Theatre and Dance Foundation (STAND). His current works “Via Kanana” and “Cion: Requiem of Ravel’s Bolero” have been halted from touring due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Comments - Please login in order to comment.