MAVERICK CITIZEN TRIBUTE

Farewell, Iqbal Master – hero doctor and a global expert on the treatment of drug-resistant TB

The devastating impact of Covid-19 on TB services in South Africa has been consistently reported by the country’s media, but some of the heaviest blows are landing relatively silently among medical professionals working on TB. The death of Dr Iqbal Master on 15 January, in particular, has left the drug-resistant TB healthcare community reeling.

“Irreplaceable,” is how Dr Norbert Ndjeka, Department of Health Drug-Resistant TB, TB and HIV director, described Dr Iqbal Master, who succumbed to Covid-19 in Durban’s Shifa Hospital on a Friday evening in mid-January.

Master served for 26 years in the TB section of King Dinuzulu Hospital in Durban, 14 of those years as manager. He also served on various national and international advisory committees.

“We have lost, I think, the most experienced treater of drug-resistant TB, not only in South Africa but in the world,” said Dr Francesca Conradie, deputy president of the Southern African HIV Clinicians Society.

Professor Graeme Meintjes, an infectious diseases specialist at the University of Cape Town, called Master “a hero who led through his actions, and made a positive difference in the lives of tens of thousands of his patients”.

To grasp the high praise of those who knew Master, it is necessary to know that KwaZulu-Natal, where Master lived and worked, is the historical epicentre of everything that can go wrong with TB. It was here that extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB) first appeared in South Africa in 2006. The province is home to thousands of patients, many of them living in poverty in rural areas and suffering from comorbidities, especially HIV.

“Basically, you could not think of a more difficult environment to work in, and Iqbal was the clinician at the centre of it all,” said US-based infectious diseases specialist Dr Jennifer Furin, who consulted regularly with Master in setting up TB activities in parts of KwaZulu-Natal.

Furin most admired Master’s “complete lack of rosy optimism”.

“Iqbal was able to see everything at once, all the challenges that lay ahead for new treatment initiatives and interventions. He would say, ‘This is going to be very hard, but you are going to do it anyway, and if you don’t, I will.’ He walked into it, and he took the rest of us with him,” Furin said.

Born on 5 December 1962, Master lived and worked largely within the borders of KwaZulu-Natal, attending school and university in Durban, and later working at a series of major public hospitals, including King Edward VIII, Stanger, Prince Mshiyeni Memorial and finally King Dinuzulu (formerly King George). He worked mostly on TB, but spent a year as a medical officer in paediatrics, and another in obstetrics and gynaecology.

Ndjeka remembered meeting Master for the first time in 2006, when it was found that 53 people in a district of KwaZulu-Natal called Tugela Ferry had contracted XDR-TB, a type of TB resistant to most anti-TB medicines.

“Iqbal already had a lot of drug-resistant TB experience at this time, and he made himself available. He said: ‘Refer these patients to me,’ at a time when there was a lot of fear around XDR-TB in the medical community,” Ndjeka recalled.

The only medicines available for the treatment of DR-TB in 2006 had been around for decades, a regimen that included an injectable antibiotic known to cause deafness and bring about other life-altering side effects.

TB committee meetings can be very contentious, with people taking very different sides on policy fights and those kinds of things, and Iqbal could always lighten the mood with a silly joke, reminding us that, in spite of the heaviness of the task, we were people, we were colleagues, we were friends.

Dr Nirupa Misra first met Master while working in pharmaceutical services at the provincial department of health, and recalled their many discussions “about Kanamycin, a terribly toxic antibiotic that was administered via painful injection”.

“We shared this goal of getting better, safer drugs for patients, and for this reason I transferred to King Dinuzulu Hospital in 2012. From that point, we were on a very special journey together,” said Misra.

In December 2012, a new drug called bedaquiline was approved for the treatment of DR-TB, and South Africa’s Department of Health as well as certain NGOs were quick to obtain access to the drug, which was provided to patients meeting strict criteria via a special access programme. In 2017, a second new DR-TB drug called delamanid was made available to certain patients in South Africa in a similar way. King Dinuzulu Hospital was selected as KwaZulu-Natal’s site for both access programmes.

“This was the new dawn we had been hoping for, but it was an immense amount of work,” said Misra.

To secure access to one of the new drugs for a patient, the individual’s clinical history would need to be written out and then submitted, with a motivation, to a national committee for review.

“Iqbal did all of that work himself, sitting up until all hours of the night capturing information on to a database,” said Misra.

Misra, Ndjeka and others remember imploring Master to delegate.

“I used to say: ‘Iqbal, why don’t you use the clerical staff from such and such a ward?’ He’d say, ‘No, man, they won’t listen to me. I’d rather just do it myself.’ He just ungrudgingly went ahead and did everything, whether it was clerical work, clinical work or pharmacy work, and that’s what was outstanding about him,” said Misra.

In the beginning, though, KwaZulu-Natal was a little slow to initiate patients on bedaquiline, which frustrated Ndjeka.

“I wasn’t happy with the pace, and took it up with Iqbal, who proved himself open to constructive critique because, not long after that, KwaZulu-Natal had more people on new drugs than any other province,” he said.

In the Western Cape, Dr Anja Reuter, working with Doctors Without Borders, was herself filing applications on behalf of patients for delamanid, and finding it onerous even though the workload was a fraction of what Master was getting through.

“At that point, the global roll-out of bedaquiline and delamanid was being tracked. I looked at the numbers out of King Dinuzulu and realised that Iqbal was personally facilitating access to new drugs for a higher number of people than most countries’ national TB programmes,” said Reuter.

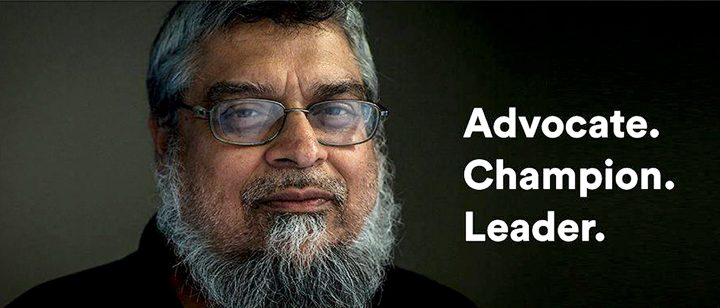

Dr Iqbal Master. (Photo: Facebook)

Thanks in no small part to the proficiency of Master and his King Dinuzulu team, South Africa ended up with the world’s largest cohort of patients on new DR-TB drugs. Using South Africa’s data, local researchers have since been able to show how the inclusion of new drugs significantly improves DR-TB cure rates. This evidence in turn gave South Africa significant influence over the direction of global DR-TB policy.

“In 2019, I nominated Iqbal to join a meeting of the DR-TB Guideline Development Group of the World Health Organisation (WHO) in Geneva, where the major data to be reviewed came from South Africa. He was so competent and resourceful, and I was really touched because this meeting culminated in a change of policy that South Africa had spent years advocating,” Ndjeka said.

The policy change in question was profound: from that moment on, the WHO recommended new, shorter regimens for all eligible DR-TB patients, with bedaquiline in place of the toxic injectable antibiotic.

King Dinuzulu remains a study site for some of the world’s most promising new combinations of DR-TB drugs, and there was no rest for the seemingly indefatigable Master.

“One of Iqbal’s lesser-known contributions has been in the area of paediatric DR-TB,” said Furin.

“He took care of hundreds of children with DR-TB, probably more than anyone else in the country, and he did it without much training in paediatrics, because it was the right thing to do,” she said.

In the paediatric ward in King Dinuzulu Hospital, there is a mural across three sides of the room, called the Wall of Knowledge with a Corner of Hope, illustrating a treatment journey in vibrant colour. At the end there is a picture of Nelson Mandela, with a quote: “Education is the most powerful weapon you can use to save the world.”

“Iqbal, like Madiba, believed in the power of education, and it is his spirit I now see in the mural, the spirit of a man who did the most incredibly caring things, without any fanfare,” said Misra.

A common refrain among Master’s colleagues is that his dry sense of humour and self-deprecating manner could improve the tone in any room.

“TB committee meetings can be very contentious, with people taking very different sides on policy fights and those kinds of things, and Iqbal could always lighten the mood with a silly joke, reminding us that, in spite of the heaviness of the task, we were people, we were colleagues, we were friends,” recalled Dr Jenny Hughes of the Brooklyn Chest Hospital in Cape Town.

When Master fell ill with Covid-19, he remained in daily contact with Misra, resorting to WhatsApp after being admitted to hospital in order to continue discussing access to medicine issues at rural hospitals.

“He writes in his last message to me, with a big smiley face, ‘If I go, I will leave the implementation of the SOPs [standard operating procedures] to you.’

“His last joke, and so perfectly characteristic,” said Misra. DM/MC

Sean Christie is a journalist, author and communicator currently working for Doctors Without Borders in South Africa.

"Information pertaining to Covid-19, vaccines, how to control the spread of the virus and potential treatments is ever-changing. Under the South African Disaster Management Act Regulation 11(5)(c) it is prohibited to publish information through any medium with the intention to deceive people on government measures to address COVID-19. We are therefore disabling the comment section on this article in order to protect both the commenting member and ourselves from potential liability. Should you have additional information that you think we should know, please email [email protected]"