REFLECTIONS ON PEACE

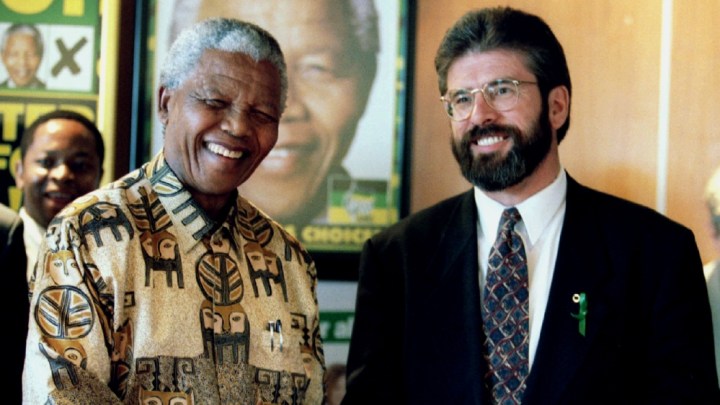

The narcissism of small differences: What the IRA learnt about negotiation from the ANC

Padraig O’Malley, a ‘professor of peace’, describes here how he developed a hypothesis: The protagonists in one conflict who have successfully resolved their differences are best positioned to assist those in another conflict. To test this theory, he and others brought leaders of South Africa and Northern Ireland to a meeting at a secure conference centre adjacent to the De Hoop Nature Reserve in the Western Cape. The relationships that developed helped pave the way to peace talks on Northern Ireland. This is an extract from a new book, Imagine: Reflections on Peace, by the VII Foundation.

I began documenting the bumpy transition from apartheid to democracy in South Africa in late 1989, in a process which involved interviewing teams of negotiators on all sides of the conflict. I had also spent 20 years preoccupied with another thorny conflict – the one that had bedeviled Northern Ireland for a generation. Born in Ireland and educated there and in the United States, I was then a fellow at the University of Massachusetts Boston with a focus on divided societies. I had convened two conferences on Northern Ireland in Massachusetts in 1975 and Virginia in 1985 and interviewed the leadership on all sides of the conflict for my book The Uncivil Wars: Ireland Today.

In the early 1990s, as a member of the Opsahl Commission on Northern Ireland, I and other commission members met with Mitchel McLaughlin, chair of Sinn Féin, the political party that spoke on behalf of the Irish Republican Army (IRA). McLaughlin intimated that the IRA had begun to debate the efficacy of the armed struggle, then in its 25th year. In order to announce a real ceasefire, the Sinn Féin leadership would have to convince the entire membership, across Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, that it was in its best interests to do so. The “wooing” would be an arduous, often emotional process, especially since there was no unanimity at that point from the IRA leadership itself.

In August 1994, when the IRA called a ceasefire, I saw an opportunity to test a hypothesis I was developing about the dispositions and perceptions of protagonists in intercommunal conflict: one divided society is in the best position to help another. Northern Ireland’s political elites had bogged down in moving from the bullet to the ballot box, and they might benefit from meeting with a cross section of South African negotiators. (The April 1994 elections in South Africa had extended the franchise to its black citizens. Nelson Mandela, the head of the African National Congress, was elected president, and FW de Klerk, who had been president, became deputy president in a power-sharing arrangement.)

Roelf Meyer, Padraig O’Malley and Cyril Ramaphosa. (Photo: citiesintransition.net)

In March 1995, after gauging support for my idea in Northern Ireland, I asked Valli Moosa, deputy minister of constitutional affairs in South Africa’s new government, whether his ministry might invite Northern Irish negotiators to meet with their South African counterparts. We both understood the obstacles that lay ahead.

I realised that such a meeting would have to fulfill a number of conditions: (a) all parties involved in the conflict would have to attend; (b) key negotiators would have to be on an equal footing – pari passu (equal footing); (c) both the British and Irish governments would have to approve; (d) President Mandela would have to give his blessing; (e) the Northern Ireland parties would have to ask the South African Ministry of Provincial Constitutional Affairs to host the event; and (f) under no circumstances could the conference be construed as involving either negotiations among Northern Ireland’s interlocutors or interference of the South African government in the conflict itself.

Moosa’s job was to convince his boss, Roelf Meyer. Meyer’s job was to convince Cyril Ramaphosa, the chair of the Constitutional Convention. Ramaphosa’s job was to open the gateway to Mandela. My job was to convince the leadership in all parties in Northern Ireland that they had much to learn from the South Africans. I had warm relations with Meyer and Ramaphosa, respectively De Klerk’s and Mandela’s chief negotiators during South Africa’s multi-party negotiation process. After my overtures, both came to Boston in June 1993 to receive honorary degrees at the University of Massachusetts Boston’s commencement ceremonies.

Ramaphosa and Meyer, arch-protagonists across a negotiating table, spent three days together, far from the madding tumult of the ongoing and intense multiparty negotiations.

Having cemented those relationships, I laid a marker for myself: Someday I would call in the chit.

The Personalities

And so began my monthly trips to Northern Ireland. Nine parties, including some associated with paramilitaries, were either centrally or peripherally involved in the conflict. All would need to be brought in; for the major ones, it would be a case of either all in or all out. I had to persuade the leadership of the major parties to participate. This included Gerry Adams of Sinn Féin, David Trimble of the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP), the Reverend Ian Paisley of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), John Alderdice of the Alliance Party of Northern Ireland, and John Hume of the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP).

I had had a longtime, sometimes difficult, but always warm relationship with Hume. In 1985, he was our commencement speaker at University of Massachusetts Boston and received an honorary doctorate. (Giving away honorary degrees is my forte!) Hume always played his negotiating cards close to the chest, sometimes to the exclusion – and chagrin – of members of his own party. He had clear ideas about peace talks and frowned on initiatives that were not his own. It galled him to see that I was talking to Sinn Féin and the DUP before he had talked to either party. I leaned on the persuasive powers of Mark Durkan, Hume’s right-hand person and top negotiator.

To ensure that the SDLP was locked into the process, it was imperative to first draw in Sinn Féin. My relationship with its enigmatic leader, Gerry Adams, was another complicated one. I had met Adams in 1980 and interviewed him repeatedly in the mid-1980s, posing questions that ranged from the personal to the political. It is almost impossible to penetrate his veneer of unflappable equanimity. (He rejects any suggestion that he was ever a member of the IRA. No one believes him.) He always left wiggle room in his interviews – he wasn’t exactly ambiguous, but he was also never closed-ended. Adams used to hold his press conferences at Connolly House in West Belfast in an auditorium outfitted for the purpose. He would arrive, make a statement, and refuse to take questions. Instead, he would call on a number of journalists and walk off; and then, one by one, they would enter an enclosed cubicle where he would entertain their questions while others waited outside to be called. It was as formal as a confessional box. In this way, he always managed his message. You messed with Gerry in an article and you would never see the inside of that box again.

I had relationships with other principals as well. I knew Peter Robinson, Paisley’s deputy in the DUP, from the late 1970s and had been interviewing him since 1981, mostly at his highly secured residence in East Belfast. I sometimes dined with him in the House of Commons. He was as unflappable as Adams but lacked the latter’s equanimity. He was sardonic – detached, amused at his own observations, and not averse to taking a shot at “Big Ian”. Robinson wanted to convince you that he did not kowtow to the Big Man.

The Big Man was, of course, Ian Paisley, the Protestant fundamentalist, firebrand, loyalist, and head of the DUP. He underscored his own sense of self-importance when I relayed to him in the early 1980s that the IRA had never contemplated killing him. (“He is far more valuable to us alive than dead,” my Sinn Féin source had said.) Paisley got upset – of course he was on the hit list, he insisted. The Big Man was against meeting with anybody, but absolutely opposed to meeting with Sinn Féin. To him, the political arm of the IRA was the devil incarnate, and the UUP, which competed for Protestant “hearts and minds”, was as much his enemy as the SDLP or, for that matter, the British government. They all had his enmity.

I first met David Trimble at the British-Irish Association’s annual conference in 1983. Trimble, a practising lawyer and one of the UUP’s brains, was a little stiff, to say the least, and people sometimes mistook his innate shyness for aloofness. He was as soft-spoken as he was hard-headed. We had mutual friends, including a very close one. The UUP represented the rump of the Unionist party that had governed Northern Ireland since the statelet’s foundation in May 1920. Paisley’s DUP was squeezing it from the right, accusing it of “selling out”, a refrain hurled at any unionist who agreed to negotiate with nationalists under the belief that such negotiations would lead ineluctably, as a result of some mysterious osmosis, to a united Ireland. On one occasion in late 1996, Trimble and I spent hours talking in Renshaw’s Hotel, Belfast – nothing about South Africa or Northern Ireland, just talking.

My approach to each of these men directly and through friends was to pose a question: “If President Mandela invited you to come to South Africa to meet with the leaders who negotiated the end of apartheid, would you come?” That more or less became my mantra for two years. Sinn Féin was the least sceptical, but was quick to tell me it didn’t need me as an intermediary, as it had its own direct line to the ANC. Any suggestion of a Sinn Féin presence met with a thumbs-down from the Unionists.

I became a fixture in Northern Ireland, setting up appointments, waiting, pondering Vladimir’s predicament in Waiting for Godot. Much of this time involved sitting around drinking Guinness, sometimes five or six pints with a double Black Bush. It was not healthy, but such is the business of pushing peace.

Bringing in the Heavyweights

After a few too many moments of “numbing it out”, it was time to call in my chit. I decided that if I couldn’t bring the leaders of all Northern Ireland’s factions to South Africa, perhaps I could try bringing the South Africans to Northern Ireland. Perhaps they could nudge the talks further. Meyer and Ramaphosa agreed. I returned yet again to Belfast with a different message: the two men who had spearheaded negotiations in South Africa were coming to Belfast and would like to meet with them. This time, there were no naysayers.

On 28 July 1996, Meyer and Ramaphosa took up residence at the Europa Hotel, in the 1970s the most bombed hotel in Europe. Over 36 hours, they met with the leadership of each party for two hours. Meyer had dinner with US Senator George Mitchell, President Bill Clinton’s special envoy – the pivotal figure outside of Northern Ireland, and the man who would ultimately guide the peace process across the finishing line. Mitchell gave his blessings, and perhaps also his misgivings, as he had already spent the better part of a year trying to simply bring the parties to the same table. Ramaphosa, on his way to Belfast International Airport, stopped to meet with Adams and McGuiness in West Belfast. On their return, Meyer and Ramaphosa reported to Mandela that in their opinion, South Africa could help. Fine, said Mandela, but my country does not intervene with the conflict in another country without being invited to do so. He required letters from all the parties involved.

I was back in Belfast. It was one thing for Ramaphosa and Meyer to believe that South Africa could assist, another for all the parties in Northern Ireland to believe so. And Mandela had set the stakes higher: all parties had to agree to go to South Africa; if one or another dropped out, a meeting there would make no sense.

Making this happen involved quite a pas de deux – or rather a pas de neuf (nine!): first, secure letters from all of them; next, meet the conditions that different parties attached; next, find a venue to accommodate the often contradictory conditions; then, perhaps most difficult of all, hold the parties to their promises to go. In the month between saying yes and departing for the journey, some of those parties began to get cold feet. Some Unionists began to tell Paisley that the whole thing was a republican setup – that the ANC and Sinn Féin were in cahoots, and how could the DUP justify going to South Africa when it refused to meet with Sinn Féin for negotiations in Northern Ireland? Different media aligned themselves with different protagonists.

Helpfully, the South Africans chose a secure conference facility adjacent to the De Hoop Nature Reserve, about a two-hour drive from Cape Town, where the media could not intrude.

In the final days, the DUP began to crack. They did not want to catch sight of Sinn Féin. They would not sit in the same room. Prolific and well-practiced at shouting “sellout” at the UUP, the DUP was hypersensitive to being called the same itself. If the DUP pulled out, Trimble would pull out, too. Each spurned the other; each needed the other’s protective presence.

A team of Afrikaners came to our help with great zeal. They divided the conference facility into three parts: one area was set aside for Unionists, one was for nationalists, and the centre was a neutral space. They assigned Sinn Féin to one area, put the DUP in the area farthest from Sinn Féin, and positioned the more moderate parties from both camps – the UUP, SDLP, and Alliance – as a buffer in the centre. Each area had its own wings with rooms and dining facilities. Each even had its own bar. Each session would be repeated twice so that all parties were receiving the same information. Ramaphosa would host and chair the whole thing.

Cracks widened in May 1997, when the Sunday People ran a feature essentially saying the Unionists were going to South Africa to negotiate with Sinn Féin. A furious Robinson faxed me: “If the present public understanding of the event remains as outlined in the Sunday People there would be no question of the DUP being present.” He continued, “We will not meet directly or indirectly with [the] IRA/Sinn Féin murder gang; we will not take part in any event that would give the impression that we were doing so outside Northern Ireland.”

That was a clanger, if ever. Nothing less would suffice than a guarantee of being “hermetically sealed” from Sinn Féin, from the moment they departed Belfast on 29 May to the moment they arrived back on 3 June. If I could satisfy them on these scores, we might squeeze through the political hoops.

On 23 May, I met with Paisley at Peter Robinson’s home. What remains most vividly in my mind is that Paisley, a huge man, had rather small ankles and wore short pink socks. I thought to myself, how could such a bulk of a man rest on such small feet? The pink socks stick with me.

I had come with a map of the conference facility’s layout, with each area marked off. The distance between Sinn Féin’s area and the Unionists’ was noted; everyone would be colour coded according to party. Yet Paisley persisted – what if this or that happened? What if the media got wind of the gathering? If they couldn’t gain access, wouldn’t that enrage them, and what kind of damaging stories might they write? After a couple of hours Paisley called it a night, saying he would let me know the DUP’s decision the following day. That evening, fearing the worst, with the conference five days away and with the departure tickets in my hands, I called Robinson. He told me that if he could get one other senior person in the DUP to go with him, he would go, even over Paisley’s objections. I called Gregory Campbell, a senior DUP MP I had become close to. Campbell agreed to go. I called Robinson back. He was all set. I called Trimble. If Robinson was going, so was he. Without Robinson he was out.

The DUP executive committee met the following day. After some discussion of a local election, Paisley flipped through his diary and asked, “What about next Monday?” “I don’t know about you, Doc,” Peter Robinson says he replied, “but on next Tuesday I’ll be in South Africa”. Robinson says that Edwin Poots, a member of the Northern Ireland negotiating forum, piped up. After hearing an explanation, Poots said he wanted to go, too. And then Sammy Wilson, also a forum member and a former lord mayor of Belfast, chimed in. Campbell, of course, was already on board. In the end, all four – the cream of the DUP negotiating team – attended.

The last piece of the puzzle was to get the British and Irish governments on board. I enjoyed a special relationship with the British Government’s Northern Ireland Office based on my authorship of The Uncivil Wars, which earned me credibility with secretaries of state for Northern Ireland. Over the years, I had met and interviewed many of them, and incoming secretaries prepped for office by reading it. The book greased tracks on the Irish side as well. The multiparty Airlie House Conference, held in 1985 in Virginia, allowed me to get on familiar terms with various senior British and Irish officials. In the spring, my access to all these contacts paid off: Dick Spring, the Irish Tánaiste (deputy prime minister) and minister of foreign affairs, and Michael Ancram, the British minister of state for Northern Ireland, signed off on the project. Dame Maeve Fort, the British high commissioner to South Africa, also gave her nod.

Overcoming the Narcissism of Small Differences

Travel arrangements were practically a paean to segregation: Sinn Féin was routed through Paris to Johannesburg, while the other parties went through London. In South Africa there were two sets of VIP lounges in Johannesburg; two sets of military aircraft (one to ferry the Unionist parties, SDLP, Alliance, and the smaller parties, and another to ferry Sinn Féin) to fly everyone to the Denel Overberg Test Range, a military base close to De Hoop; and two sets of buses to the De Hoop Nature Reserve.

There were three sets of accommodations within the conference site. The conference itself held two separate sessions for each proceeding. Finally, a set of byzantine arrangements allowed the delegations to either commingle or remain separate.

On the morning of 30 May, the negotiators from Northern Ireland arrived in two groups. The luggage had been carefully tagged in Belfast. When the first plane landed at Johannesburg, suitcases were unloaded on the runway and the group straggled to a waiting Hercules 130, the huge carrier’s backside open to a cruel winter wind as we waited because of a delayed takeoff. Trimble read William and Mary; the others slept, chatted, or huddled against the cold.

After Robinson had settled in his accommodations, I was anxious to show him what a good job we had done in complying with the DUP’s demands. We reviewed the arrangements, and he had only one comment: “The Sinn Féin bar is bigger than our bar!” I pointed out that his group didn’t even drink. He was adamant – we had to fix it. This small incident exemplified a key characteristic of a divided society: the narcissism of small differences. To Robinson, the fact that the makeshift Sinn Féin bar was slightly larger than the makeshift DUP bar triggered a less-than, more-than complex; it signified that the organisers empathised with Sinn Féin’s position. It had to be fixed, so we fixed it.

Later that afternoon, the Sinn Féin contingent arrived. Overall, 27 members of nine political parties settled in.

The dinners proceeded on schedule, and the South Africans began to arrive — 16 negotiators from all parties to the South African talks, as well as members of the security and intelligence services. (Ramaphosa, never a man to be where he absolutely does not have to be, arrived the next morning.) South Africans retire early, so their negotiators quit us, leaving only the Afrikaners whose job it was to keep people separate. (They had even hauled in potted trees to make sure that no member of the DUP might ever catch sight of a member of the Sinn Féin delegation. The centre bar was the place to be. Everyone piled in, in ones and twos. As neither the Sinn Féin nor the DUP delegates drank, the centrists surreptitiously sized each other up like boxers before the opening bell. They didn’t interact.

Then, suddenly, from a Unionist came the full-throated strains of The Fields of Athenry – a song dear to the heart of nationalists, a song belted out in bars across the Republic and the Catholic north on various and sundry occasions, the litmus test of culture. Heresy! The Irish applauded generously and kept their powder, but then rose to the challenge when the Unionists, with a faint taunt, called, “Up to you, lads!” They proceeded to offer an equally full-throated rendition of The Sash My Father Wore, a Northern Ireland and Ulster Scots folk song commemorating the victory of the Protestant King William over the Catholics supporting King James in 1690, as well as other glories of the Orangemen.

And so the night went: The Foggy Dew, from the Unionists; Lisnagade, from the Nationalists; Four Green Fields, Unionists; The Patriot Game, Unionists. It was a madcap competition to see who could sing more of the other’s songs. The beer went down, and the Afrikaners added a few songs of their own honouring various exploits during the Boer Wars. Some got a little maudlin, carried away by the moment and the exhilaration of being part of something that might break the mould of history. The craic was great, God was good, and the night was long.

At about midnight, I noticed a figure skulking among the potted trees the Afrikaners had positioned. Out of the shadows came one who shall remain unnamed (for the sake of his political future), breaking DUP curfew for the sake of a pint. He cut a lonesome figure, huddled furtively in the shadows of the now-capacious DUP bar.

Rising to the Occasion

Over the next three days, the engagements were intense — lectures, workshops, and private consultations, all occurring in duplicate. Robinson had demanded, on behalf of the Unionists, that “no disadvantage would be felt by our delegation because of these self-imposed conditions and that no event would be arranged for collective delegations that would not apply separately to ourselves”. None was and none were. The risk that the other side (or your own side) would see you as soft ensured that there was no overt commingling, but in private arrangements with South Africans as facilitators, a little shuttling back and forth may have discreetly occurred. (Our own commitment to not publicly disclose what took place means I’ve decided to allow the South Africans to keep such arrangements to themselves – it was their show, not ours.)

The meeting allowed both Sinn Féin and the Unionists to speak with members of the South Africa delegation. Sinn Féin formed a bond with Ramaphosa, and the Unionists connected with Meyer and the Afrikaners. Later the Irish contingents would each talk with their respective South African mentor – who, unknown to them, would talk to his counterpart and then get back to them.

By mid-morning on Saturday, 1 June, the breakthroughs that Ramaphosa had expected had not occurred, to his disappointment. It was time to bring in Madiba, as Mandela was affectionately called. The president arrived at noon on 1 June. But we had a problem. The DUP refused to meet with him if Sinn Féin was also in the room. The UUP fell in behind the DUP.

“You are going to have to endure a little apartheid here,” I said, greeting him on the tarmac as he walked from the helicopter. He laughed.

He met with all parties together, minus the two Unionist ones, then separately with the Unionists. This was for the better. To Sinn Féin, he stated in no uncertain terms that it would not be included at a negotiation table unless the IRA reinstated the August 1994 ceasefire it had ended in February 1996 with a bombing at Canary Wharf. To the Unionists, he insisted that they decouple two demands (that the IRA declare a permanent ceasefire and that it decommission its weapons). Mandela told them to insist on the ceasefire but to make decommissioning part of the negotiation process, which is what happened.

Trimble was chagrined because the hoped-for private meeting with Mandela did not materialise – for obvious reasons: if one delegation was afforded such access, all would have to be. I corralled the copy of Mandela’s autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, that my assistant Margery O’Donnell had brought with her and handed it to Ramaphosa, who was introducing members of the Unionist delegations to Mandela. On a piece of paper I had written, “Cyril, please ask Madiba to sign this book as follows: ‘Dear David, you are one of the few people who can bring peace to your troubled country. I know you will rise to the occasion. Your friend, Madiba’.” Cyril glanced at it and handed the book with the instruction to Mandela. The ever-astute Mandela didn’t miss a beat, inscribing it as asked. When the meeting broke up, I sought out Trimble and told him Mandela had a gift for him – a copy of his autobiography, which he had inscribed. “Read it!” I said. And after Trimble read the inscription, his face broke out in a big smile.

Each party lined up in turn to have a photo op with Mandela. The ice cracked, and the programme went into high gear. All the demands of the participants were met. On 20 July 1997, the IRA announced a new ceasefire, and subsequently Sinn Féin was admitted to the peace talks.

On 10 April 1998, all parties signed the Good Friday or Belfast Agreement. The meeting at De Hoop played a limited role in that outcome.

I took to referring to the meeting as the Great Indaba, using the Zulu word that has found widespread use throughout Southern Africa to mean, simply, gathering. Jeffrey Donaldson, an Ulster Unionist negotiator, called the indaba “a game changer”, explaining, “We were able to take the lessons we learned from the South African experience and apply them to our own.” Monica McWilliams, head of the Women’s Coalition, said, “It couldn’t have been planned to happen at a more critical point.” Irish Taoiseach (Prime Minister) Bertie Ahern acknowledged that the Great Indaba was “highly complex” but led politicians to believe “this problem could be cracked”. In a year, he added, the participants were able to make “the enormous moves they had not dared to dream [of] for the previous 60 to 70 years”.

The late Martin McGuiness said of the experience, “Groundbreaking! I found that I could learn to love my enemy”. And an observer later wrote of David Trimble, in a description that also applied to the other participants, “On a distant field of a South African game park, he began the journey in earnest from leader of one tribe to the architect of a new inclusiveness in Ulster.” DM

Padraig O’Malley is an Irish peacemaker, author and professor at the University of Massachusetts, Boston who specialises in the problems of divided societies, such as South Africa and Northern Ireland. He has been actively involved in promoting dialogue among representatives of differing factions.

This is an extract from the book: Imagine: Reflections on Peace, by the VII Foundation. The question behind the book is: Why is it so difficult to make a good peace when it is so easy to imagine? The expansive book unravels the complexities of redemption and rebuilding in Bosnia & Herzegovina, Cambodia, Colombia, Lebanon, Northern Ireland, and Rwanda. For more information visit www.reflectionsonpeace.org.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.