CONVERSATIONS

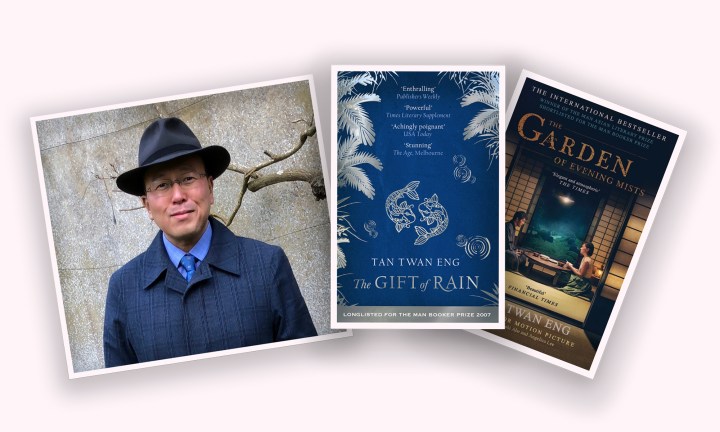

Tan Twan Eng on the ‘small human events’ that shape his powerful novels

‘How else can we understand another person if we don’t regard him or her as a fellow human being? Every character I write must be alive, must come off the page, and the only way to accomplish that is to see them as people, with all their strengths and flaws, right from the very beginning’, says author Tan Twan Eng.

Tan Twan Eng was born in 1972 in Penang, a coastal city of Malaysia; he grew up in Kuala Lumpur, the country’s capital, thus describes himself as “very much a city boy all my life”. Later, he came to South Africa to do a Master’s degree in law at the University of Cape Town.

In 2007, Tan published The Gift of Rain, followed five years later by The Garden of Evening Mists; both novels have received international acclaim and he was subsequently nominated for the Man Booker Prize; The Garden of Evening Mists also won the prestigious Walter Scott Prize for historical fiction.

Tan sets his stories in specific moments in time, layering each narrative with rich colours and complex storytelling. Both novels delve deeply into the time of the Japanese Occupation of Malaya (1941 – 1945) and the agonising impact it had on the people who lived through it.

“I do most of my research from books and archives. I always look at the footnotes – they often contain the small, human events and stories that don’t make it onto the grand theatre of events. It’s in the footnotes that I have sometimes unearthed the most illuminating angles to view the larger picture, a gate into the heart of a complex story. Rarely do I interview people as part of my research,” he explains.

When reading his novels, one gets the feeling that every sentence was carefully picked, in a deliberate way, that seems to mimic the design conscious choices found in the Japanese gardens Tan writes about, or the aikido movements he explores.

Tan agrees: “I consciously dwell on what I’m doing when I write. I have to decide which word to use, the structure of our sentences, the placement of punctuation marks, the scenes I wish to describe to move the story along; I have to ascertain that the dialogue is realistic; I have to control the mood, the tone, the atmosphere so that it works for the entire book. Writing a novel is not an automatic, repetitive action like riding a stationary bicycle or swimming laps in a pool”.

The Gift of Rain is narrated by Phillip Hutton, a half-Chinese, half-British sixteen-year-old son of one of Malaya’s richest shipping families. With World War II looming, Philip meets Hayato Endo, a Japanese diplomat and aikido master who lives close to their home and who becomes Philip’s mentor. Their idealised relationship tumbles when Philip realises that Endo is a Japanese spy; the story is a reflection on their bond and conflicting loyalties.

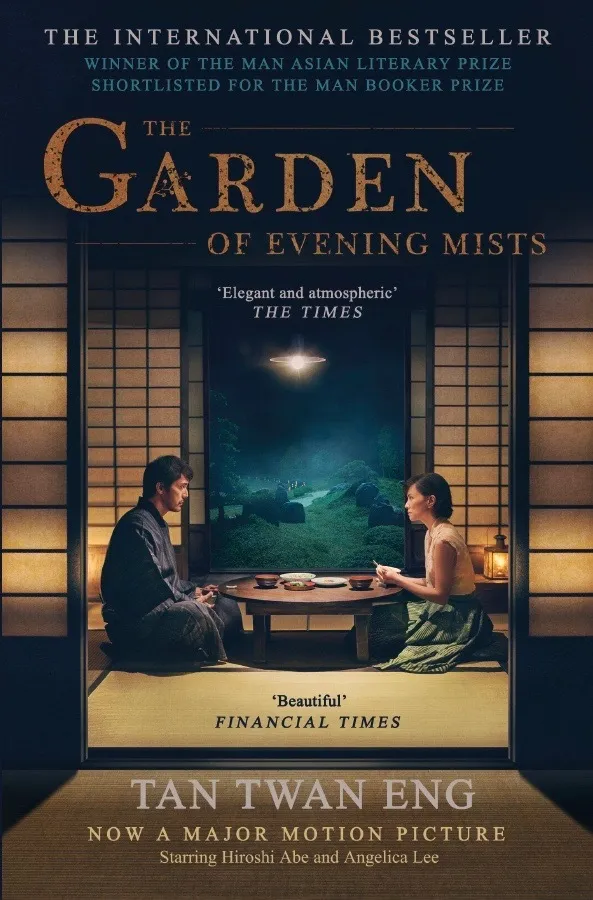

In The Garden of Evening Mists, the novel follows the recently retired Supreme Court judge Teoh Yun Ling, who returns to the Malaya highlands, hoping to find peace as she suffers from the decline of her mental faculties. The book becomes a series of chronic flashbacks that explain her time as sole survivor of a prisoner of war camp and an intriguing relationship with the former gardener of the Emperor of Japan.

Tan’s novels are lush, dense and conjure up vivid imagery of life in the Malaya highlands or along its humid shores. In both stories, one of the main characters is Japanese, and both had some affiliation with the Japanese during the Japanese Occupation of Malaya.

Japan, the war and history

“My father was just five years old when the Japanese invaded Malaya. His family had to evacuate from their home in town and hide in the countryside, but to him it all seemed like a great adventure,” Tan recalls.

He adds, “When I was very young, my mother, who was born after the war, told me how one of her aunts was watching a movie in a cinema when Japanese troops burst in and started firing their guns wildly. Because her aunt was so short, the bullets missed her and hit the heads of the people seated in front of her, showering her in their blood”.

Thus, the theme of war becomes a constant, allowing Tan to explore the moral and practical conundrums that such events throw people into. “It’s the hardest thing to do, to beat against the tide of history, especially when there’s a high probability that it might result in torture and a prolonged and painful death, not only for you, but for the people you love.”

Every character I write must be alive, must come off the page.

Yet, his writing is never accusatory nor does it clearly define one character as evil. Instead, Tan’s writing is about nuances and the humanity that is our common thread.

“I wish to understand. And how else can we understand another person if we don’t regard him or her as a fellow human being? Every character I write must be alive, must come off the page, and the only way to accomplish that is to see them as people, with all their strengths and flaws, right from the very beginning,” he notes.

Indeed, for Tan, periods of “great uncertainty and change affect people’s lives. Moments in time when the world is changing bring out the best and worst in people”.

This is not the only connection with Japan – in his late teens, the author turned to aikido – “one of the most traditional and spiritual of Japanese martial arts, rooted in the Shinto beliefs of its founder”, he says – and for 12 years practised relentlessly. “I was obsessed with it… I knew that if I wanted to excel in it, I’d have to study its origins. Aikido was the doorway through which I entered into the heart of Japanese culture and history,” he explains.

On love and memories

Then, there is love – intense, complex and in abundance. Both novels follow the intercultural relationships between the two main characters, Philip and Endo-San, and Yun Ling and Aritomo. But Tan is hesitant to attribute the force of their friendship purely to the cross-cultural nature thereof.

“The intensity arises not solely from the fact that it’s forbidden, but from other factors and events happening in their lives too. It’s illuminating to write about characters where the dynamics of their relationship appear, at first glance, unequal, where one person appears to be more dominant than the other, because of age or experience or advantage.

“But sometimes the supposedly weaker person is, in the end, just as strong as the other person, if not stronger. And that’s when things get compelling for me.”

The Garden of Evening Mists is a more reflective novel, focusing on looking back at traumatic events, through the universal languages of love and loss, precipitated by the main character, Yun Ling’s gradual loss of memory.

Tan is fascinated with the concept of memory and the processes behind what we remember and what we decide to leave out. He is interested in “the way we remember, interpret and revise our memories. This transforming force of memory; people view the past in various ways… With dispassion, with sentimental longing, or with hatred. Nostalgia is just one way of how one chooses to deal with one’s memory”.

‘Perhaps she’s the wiser one. To forgive, to put the bitterness aside and get on with life’.

Because the novels are set in this period, questions around what happens when the war is over and peace returns are predominant in the story he tells.

“How do people reconstruct their lives and deal with what they had lost? How do they reconcile themselves with the things they had to do in order to survive, their principles and beliefs which they had to betray?” he ponders. In The Garden of Evening Mists, the narrator Yun Ling says, “For what is a person without memories? A ghost, caught between worlds, without an identity, with no future, no past.”

This is a question the author juggles with even today: the place of events in history and how we should be remembering them. He recalls a day when, trying to escape the midday heat, he finds refuge in St George’s Church in Penang. While sitting on the pews, he notices a Japanese couple enjoying a tour of the church; the tour guide tells them about the history of the place.

“[The tour guide] was telling the couple how the roof had been bombed by Japanese planes in the war. The Japanese man looked sombre. ‘Very bad, the war,’ he muttered stiffly. ‘Sorry, very sorry’,” Tan remembers.

“The church volunteer brushed away his words. ‘It’s okay, never mind, long time ago,’ she said, smiling. ‘All forgotten already.’ I looked at her and thought, ‘No, it’s not okay. And it shouldn’t be forgotten.’ But a few moments later I said to myself, ‘Perhaps she’s the wiser one. To forgive, to put the bitterness aside and get on with life’.”

A delicate ode to South Africa

The first page of The Gift of Rain starts with these lines:

“En vir Regter AJ Buys wat my geleer het hoe om te lewe.”

Roughly translated from Afrikaans it means, “And to Justice AJ Buys who taught me how to live”.

A similar tribute can be found in The Garden of Evening Mists, equally lyrical.

“Opgedra aan AJ Buys – sonder jou sou hierdie boek dubbel so lank en halfpad so goed wees. Mag jou eie mooi taal altyd gedy.”

Which translates to, “Dedicated to AJ Buys – without you this book would have been twice as long and half as good. May your own beautiful language always thrive.”

Asked about his connection to our country and how it influenced him, Tan says, “South Africa’s wide open spaces and limitless skies, the vast emptiness, the bleakness of the light and the desolation of the landscape made me rather anxious. But they also taught me to pay more attention to the world around me, to appreciate the natural world more”.

The author is also influenced by Cape Town’s large Malay population. “Seeing the Cape Malays when I was in Cape Town gave me the sensation that I was back home in Malaysia. There were the odd moments when I wanted to speak Malay to them, but then I realised they wouldn’t understand me.

“There are some similarities in their cuisine with ours, and of course Afrikaans has a number of words with Malay origins – these strengthen the feeling of familiarity, but also, at the same time, the sense of disconnect,” he notes. Tan’s novels are layered with personal references, incredible research and dipped into history. “Each reader will have a different response to my books, and I don’t wish to disillusion them or disappoint them. Reading a book is such a personal and private activity, each reader will take something different from my books,” he says. DM/ ML

Thank you Karel for this article about Tan Twan Eng’s work. I have read and enjoyed both his books, and found it very interesting to learn from the author himself how he approaches his work.

Well done on an exceptional article, Karl. Tan Twan Eng comes across as a highly intelligent and intuitive writer. Both his novels capture the essence and rare art of fine writing.