Love letter to social justice activists

It’s time to riot – putting poetry back into activism

Politics is pivotal to people’s well-being and existence, yet we write about it in a way that is often predictable and dominated by one-dimensional men. One-dimensional writing disconnects politics from our being and makes us numb. These angst-filled times demand that we rediscover and describe the poetry in politics.

- The possibility of poetry: Read and Riot

Turkish novelist Elif Shafak is a contemporary writer who is full of wonder at the world. Her novels often have an element of fantasy and imagination but her subject is always politics. In 2006, words spoken by fictional characters in her novel The Bastard of Istanbul were used against her in a trial for “insulting Turkishness”. Since then she has become a target for authoritarian President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Truth can be incendiary.

Shafak is also a respected political scientist. She describes our times as the “age of pessimism” and she too is worried about political language. Last year I attended a lecture she gave in Oxford where she fretted that “the opposite of goodness is numbness”, arguing that “when enough people become numb, evil people can do horrible things”. For this reason, her plea was for more story-telling: “emotions matter, emotional intelligence matters…. If we don’t put thought into emotions, feelings, perceptions and things that might not be easily turned into numbers or data or measured we cannot understand the world today.”

Shafak is right.

When political expression doesn’t move us, people remain immobile in the face of outrage.

If political analysis doesn’t excite our emotions it won’t transfer energy or possibility.

These days it’s invariably the stuff of anger – but it makes most people resigned, not angry. As a result, according to British spoken word poet Kae (formerly Kate) Tempest in her epic poem Let Them Eat Chaos, we go through life:

Thinking we’re engaged

when we’re pacified

Staring at the screen so

we don’t have to see the planet die.

What we gonna do to wake up?

We sleep so deep

It don’t matter how they shake us.

Even before hearing Shafak that night, I had been toying with these thoughts for a while. They came knocking every time I heard a song or read a book that evokes our civilisational crisis better than social justice activists; every time the mere act of reading made me want to get off my couch and throw stones.

But it was the chance discovery in Love Books (do visit their magical grotto here) of Nadya Tolokonnikova’s Read and Riot, A Pussy Riot Guide to Activism, that really set my feelings on fire – and made me begin to compose this article.

Tolokonnikova shouldn’t need an introduction. That she probably does, points to a related problem. Activism increasingly operates behind fake borders, forgetting that the universality of injustice meant that, in the past, activists always operated and dreamed across borders. Too many of us have internalised a nationalism of the soul.

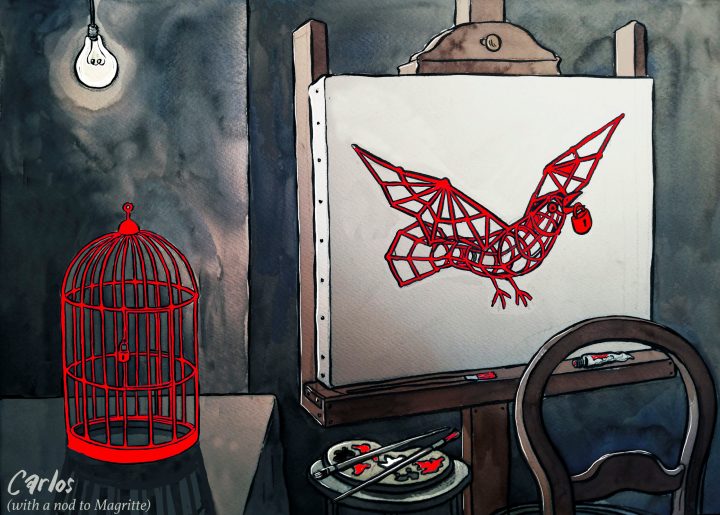

So, for the uninitiated, Tolokonnikova is one of the founders of the Russian feminist punk band Pussy Riot. In Russia, protest is mostly outlawed, so the band acquired notoriety for its 40-second performance of a Punk Prayer in the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow in 2012.

The Punk Prayer protest against Putin and the leaders of the Orthodox Church resulted in Tolokonnikova and Maria Alyokhina being arrested, tried and sentenced to two years in prison, some of it in a prison colony in Siberia.

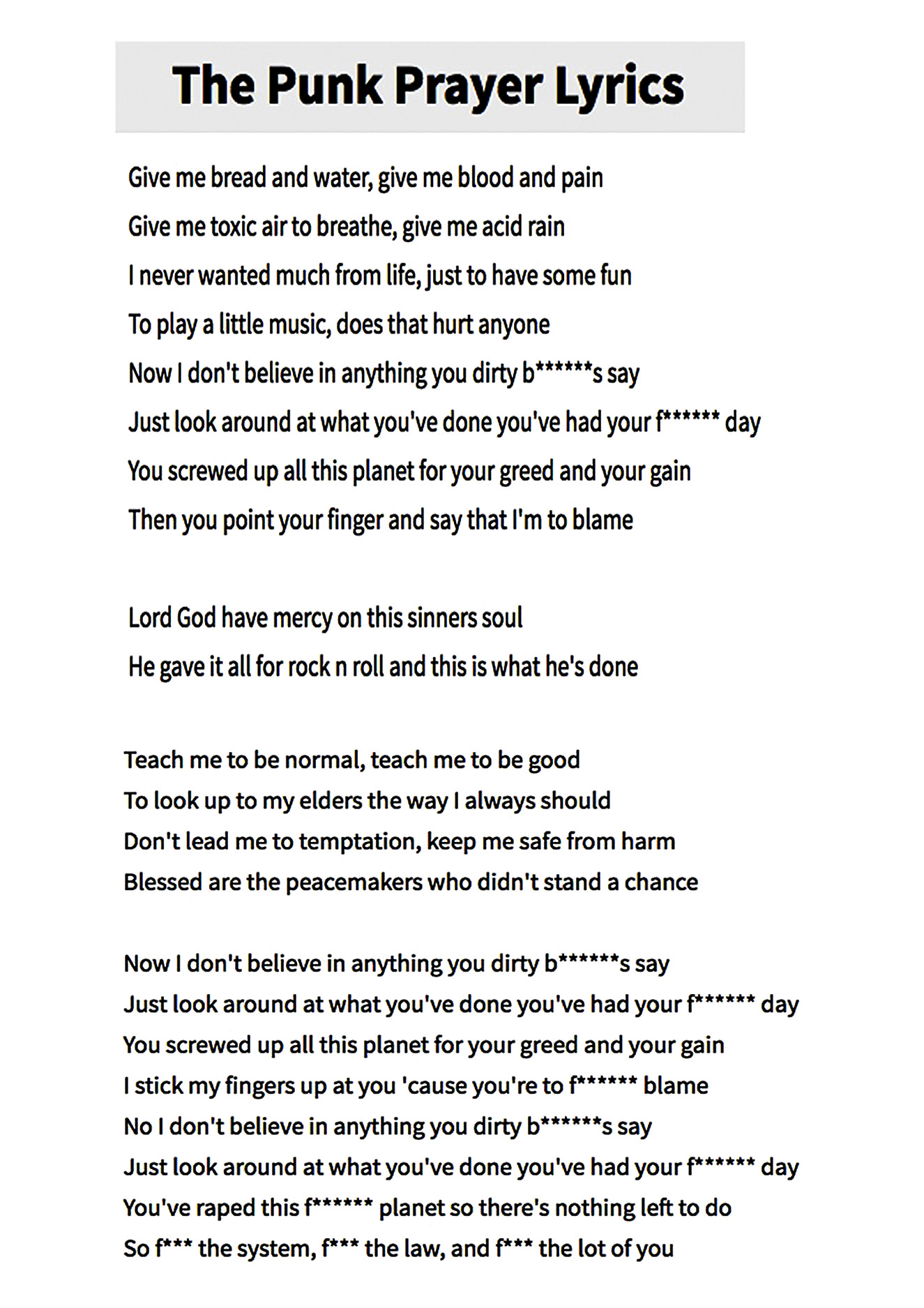

The punk prayer.

But, like many Russian dissidents before her, Tolokonnikova found freedom (of sorts) in prison. Her Guide to Activism is a kind of prison memoir, interspersed with reflections and anecdotes about life behind bars. The book’s beauty is that not only is she unbroken, but she is also unrepentant. Her belittling of Vladimir Putin, and his partner in crimes Donald Trump, is ferocious and unforgiving.

“When I’m going through Putin’s qualities and can’t find anything of worth, I unwittingly start to think about another petty person I know. Trump is his name…. In Trump and Putin’s world, we don’t really care about human dignity; we care about human capital. Dignity is not profitable.”

She labels them “misogynist douchebags” and Pussy Riot’s 2016 “song” Straight Outta Vagina is their perfect “riposte” (a polite way of saying “fuck you”) to a sexist president.

The Sex Pistol’s lead singer, Johnny Rotten, whose song God Save the Queen (here) made it to number one during the Queen of England’s Silver Jubilee in 1977 and was banned by the BBC, titled his autobiography Anger is an Energy, and it’s Tolokonnikova’s energy, artistic imagination and desire to resist by subverting that literally jumps out of the Guide. Siloes are smashed as philosophers, rock stars, poets, prisoners and revolutionaries fill her heroes’ narrative, each accorded a place as instigators of riots.

But, while she belittles Trump, Putin and elite power, she also challenges social justice activists, imploring her readers to “commit an art crime”, “make your government shit its pants”, “spot an abuse of power”.

She appeals that we:

“Bring joy back into the act of resistance. For some weird reason political action and fun have been basically separated for decades. It comes from the professionalisation of politics. I believe we’ve lost the connection between our existence, something that personally touches us, and politics.

“It’s up to us to reshape what politics is. Take it back. Bring it to the streets, clubs, bars, parks. Our party isn’t over.”

And she means it.

Even though its subject is politics, her writing is still infused with joy and love; wonder at human beings (even the bad ones), human capability and human power. Hers is a manifesto that should re-energise a tired and greying (literally) movement.

***

Tolokonnikova’s call to riot reminded me of black British poet Linton Kwesi Johnson (aka LKJ). His 1970s and 1980s poems bottle the feeling of exuberance and unshackling that comes with being involved in an uprising. In his poem Di Great Insohreckshan which celebrates the 1981 Brixton “riots” LKJ recalls exultantly:

It woz event af di year

An I wish I ad been dere

Wen wi run riot all ovah Brixtan

Wen wi mash-up plenty police van

Wen wi mash-up di wicked wan plan

Wen wi mash-up di Swamp Eighty-wan

Fi wha?

Fi mek di rulah dem andahstan

Dat wi naw tek noh more a dem oppreshan

Yet, in keeping with the theme of this reflection, in another poem, Independant Intavenshun (listen here), LKJ doubts the ability of political rhetoric of the left to ignite popular anger or to resonate with the experience of oppressed people. Ironically, one of the anthems of rioting of the time came from The Clash whose political call to arms, a song called White Riot, was envious that “black man got a lotta problems, but they don’t mind throwing a brick”. The Clash wanted “a riot of our own”.

In this age of extremes and inequality, reading should be a reawakening and a prelude to rioting.

Yet rioting can take many forms. It may involve “burnin an lootin’ ” (celebrated by Bob Marley), but it may also be a riot of the soul; a tearing up of all things fake, a putting up of mental barricades.

As Kae Tempest reflects on Great Britain and its penchant for “harking back to dead times and dead thinking” calling on “the pillars of dead men/stifled and unloving”, she writes about “Feeling the onset of riot” in her own quiet thoughts, but then reflecting:

But riots are tiny

though systems are huge

Traffic keeps moving,

proving

there’s nothing to do.

Coz it’s big business, baby,

and its smile is hideous.

Top down violence.

Structural viciousness.

Your kids are dosed up

on prescriptions and sedatives

But don’t worry ’bout that, man.

Worry ’bout

Terrorists

In between these broken lines, in their gaps and spaces, Tempest has a message: riots are not enough. A reawakened political consciousness is also necessary. Something more is needed, a more systematic, sustained, multi-pronged confrontation with the forces that numb us. If we slow down and dwell on it, if we find solitude enough to read and feel, a poem will reveal its political message to us.

In this era of anxiety, words have been co-opted by the enemy, weaponised on Twitter, made to march in threatening lines like the hammers drawn by Gerald Scarfe in Pink Floyd’s The Wall.

In our age, poetry and poetic disruption become the last refuge of ambiguity and nuance. Paradoxically, it is through ambiguity and the breaking up of the abnormal normal that we can subvert fake meaning and find a common purpose to riot again.

Fortunately, there are many artists who create poetry out of spontaneous revolt – witness the guerilla installment of a statue of Black Lives Matter activist Jen Reid that replaced the slave trader Edward Colston on the plinth he had occupied in Bristol, UK, for a century.

On the other hand though, too few activists seem to seek the emancipatory possibility in poetry.

- On Left-speak

Once upon a time, all over the world, poets were revolutionaries; and revolutionaries were often poets. But revolutionaries ceased being poets.

As a result, the numbing effect of political discourse isn’t just a problem that we can lay at the door of the mainstream media and its phalanx of political analysts. It’s also a problem with the approach of many socialists and social justice activists.

So much of the language activists use, even our actions, is dry, defanged, unimaginative.

Ask yourself: What if the language of political activism cauterises rather than awakens consciousness?

As a result, these days there is plenty of data to show how many people turn to music, fiction, art and even comedy if they want to be lured to deeper political thought. Try, for example, Bernardine Evaristo’s Girl, Woman, Other for a disquisition on racism and gender in Great Britain. Far more powerful than anything you will find in an anti-racist, anti-capitalist journal – and with a far larger audience who might be prompted to want to fight racism after reading the novel. Paradoxically, some of our most searing political analysts, with the largest readership/viewership/listenership are comedians like Jonathan Pie and Trevor Noah. In South Africa, Mike van Graan provides some of the best commentary on contemporary politics.

The problem is not new.

The mildewed effects of left-speak was commented on long ago by writers like George Orwell, in his essay Politics and the English Language, where he complained about:

“modern writing … [which] consists in gumming together long strips of words which have already been set in order by someone else, and making the results presentable by sheer humbug. The attraction of this way of writing, is that it is easy.”

Orwell’s masterpiece, Nineteen Eighty–Four, was in many respects a novel about how authoritarian governments prevent radical thought, the type of thought that causes people to riot, by appropriating language and art.

John Lennon was only nine when Orwell died of TB in 1949. But I imagine them as birds of a feather when it comes to the relationship between revolution and art. December 8th will mark the 40th anniversary of Lennon’s assassination in 1980 and its likely that there will be a wave of remembrance. However, it’s worth recalling that Lennon was both a revolutionary and a poet. But although he was sympathetic to radical change he didn’t think it would be catalysed by talking about Lenin or Mao, “the subjective factor”, the crisis of capitalism or dead Marxist saints. When the Beatles’ song Revolution was released in 1968, a year of riot and rebellion (“All Power to the Imagination!”) the song was heavily criticised by the left, oblivious as usual to nuance and Lennon’s ambiguity. His trepidation and uncertainty about revolution – “don’t you know that you can count me out/in” – was a much more accurate reflection of the mood of “the masses”, raising questions that needed conversations not political correctness.

A year later, in a run-in he had with a socialist writer over whether he had “sold out” Lennon PS-ed his letter:

“PS – You smash it – and I’ll build around it” (prophetic words in our time when building around and over and through capitalism is our best chance of ridding ourselves of it).

A rare recording exists of an interview between Lennon, Yoko Ono and Tariq Ali, a respected black activist and writer in England. Lennon, the hero of working-class youth, is patient and cordial as Ali talks down to him about “accumulated contradictions”, Marx, and “popular violence versus individual terrorism”. But although they share the same sentiments they are speaking different languages.

Not surprisingly, a little later when Ali wrote to Lennon asking for money to support the publication of Red Mole, his Marxist newspaper, Lennon replied:

“after carefully trying to read your paper – which as far as we can see can never have anything but a limited intellectual appeal to a few students, we’ve decided it would be a complete waste of money to cough up £15,000 to print even more words. … our primary concern must be to revolutionise thru art.”

The difference between Lennon and Ali, Red Mole and Imagine, was that Lennon still utilised language in a way that catalysed emotion, then understanding, then anger.

A few years later Lennon moved to New York and made common cause with radicals in the Black Panther Party, John Sinclair, Allen Ginsberg and the women’s movement (watch these videos). His politics became more overt, hence the interest the CIA took in him.

But Lennon’s enduring power has not been because he “converted” to the rhetoric of revolutionary politics, but because of the way he combined words with music to mobilise indignation and activism.

The lesson: Art and activism are twins – yet they have been successfully separated, their advocates and audiences segmented and siloed.

In places where activists have to hide from prying police – as they do now in China, Hong Kong, Russia, Zimbabwe – it’s understandable to speak in code. But there’s a problem when in a democracy like South Africa’s – with hard-won rights to freedom of expression and artistic creativity – activists’ day-to-day language sounds like the secret language of a sect, incomprehensible, full of acronyms, references to socialist saints. This was lampooned by Monty Python in their film Life of Brian, which, for other reasons, was banned in SA.

Spot yourself here? We may resent being made fun of. But we are our own worst enemies because sectarian language ends up being a way of keeping people out when activists are meant to be letting people in; a way of talking but not listening.

When I set out on my journey on the struggle for freedom and equality in South Africa, I was inspired by a collection of poems that had taken me inside the hearts and emotions of black people whose images and oppression could only be seen in photographs by the likes of Peter Magubane.

I was in England and in particular I remember a compilation of poems titled Voices From Within, edited by Achmat Dangor and published by Ravan Press in 1990. In it was a poem by Mongane Wally Serote, What’s in this Black Shit.

The anthology had a blue cover and I carried it around for many years dipping into its raw emotions for fuel. When I returned to South Africa in 1989, I couldn’t bring it with me. Eventually, sadly, it disappeared with my few possessions left over from another life in another country.

That was 30-some years ago.

The world and South Africa have changed since then. The struggle against apartheid has given way to an on-off and on-again struggle against elite capture and inequality. Serote’s “black shit” gave way to Maishe Maponya’s Da’s Kak in Die Land, a collection that takes its title from a poem about the lonesome death of Michael Komape in the shit at the bottom of a pit latrine.

When textbooks are fed to crocodiles

In Limpopo rivers they never had teachers

Faeces must fly all over the faces of politicians

Hurled by the people

Hurting

For they hurt deeply

After poems like this it feels like the wheel has come full circle. Today, in post-apartheid South Africa, black children’s lives still don’t matter.

But the basic unifying power of poetry and art has not been extinguished. When Johnny Clegg died in July 2019 the trans-class trans-race welling-up to mourn his life and celebrate his catalogue of music revealed that there is still possibility for empathy and solidarity.

Some may mock Clegg’s “soft” multiculturalism and his ability to cross over audiences, but as Richard Pithouse pointed out in this tribute to Clegg, “make no mistake, he was a dissident”. The public outpouring of loss and lost possibility that we witnessed in the days following his death wasn’t just nostalgia among those for whom Clegg had been a soundtrack to their political awakening. It hinted at something deeper. His songs, his words, his integrity had awakened the poetry that still simmers within us. Pithouse calls Clegg’s death the start of “a process for becoming a collective ancestor for South Africans and others around the world whose lives have been touched by his music and deep empathy with the oppressed”. For me that suggests we have a collective ancestry based on unity, solidarity, empathy and equality between humans.

The death of Hugh Masekela – whose riot with life is described so vividly in his autobiography, Still Grazing – evoked something of a similar response. There is something deeper in our being that is capable of being called back to life if only we would talk to it.

In South Africa, the poetry that wells up from within us in response to the moral and actual corruption we have had imposed on us by the new elite(s) has not been extinguished. But it has been pushed to the margins. Poetry books are harder to come by; poets have retreated from public spaces and been separated from activists; we only recognise them when, like Bra Willie, they die.

Nonetheless, if you look, you will see there is still poetry all around us. The problem is that in the age of the internet, through mediums like Twitter and Facebook, the pace of engagement moves our sensory experiences along too fast to allow us to take notice. So, seeing poetry is also partly about slowing down, the quality of our seeing and the quality of the response it elicits.

During the first phase of the Covid-19 lockdown, Maverick Citizen published over 50 South African poems in a series we called Unlocked: Poems for Critical Times, edited by Ingrid de Kok (read here for the last of the series). Intentionally, most were not overtly political poems. They are poems that we hoped could help us to see and understand the meanings of Covid-19, to find “clarity, confrontation or comfort” and to appreciate “both the burden and beauty of words and the spaces between words” and thereby to see what De Kok called “the preciousness as well as precariousness of the everyday”.

Without poetry we risk becoming one-dimensional in our understanding of protest and how people riot. But these days there’s very little poetry and therefore power in most activism in South Africa. We rail against inequality in monochrome and monologues. We describe surfaces but make no effort to engage with what is roiling beneath them. We think resources are what we can get from donors.

We are already far gone and that is why it will require a greater effort than ever to bring poetry back into the political discourse.

Yet, witness the power of the performances of A Rapist in Your Path originating from Las Tesis in Chile or the rapping of Pilato in Zambia and how this unnerves power. Pilato has been arrested several times. Members of Las Tesis are being prosecuted. The fear is that when feelings erupt and are expressed in a form that captures the imagination of millions, there really is no stopping them.

Las Tesis.

(Photo: desinformemomos.org/Wikipedia)

They become a real threat to the status quo: paradoxically, protest stops being performance.

During the first half of 2020, activists regrouped and worked heroically to save lives in the Covid-19 pandemic, but we did so mostly without enough imagination to break out of our ghettos. We did so without making alliance with “creatives” whose disquiet is being expressed through art or whose ability to still see and describe the essences of beauty – they at least are not yet blind – can make people wistful for a better world.

For example, this year’s virtual National Arts Festival was held under lockdown. Despite this, at multi-various performances, “subjugated voices took centre stage”, as described in this article by Niren Tolsi and probably did much more to depict the cries of the excluded and the crimes that flow from inequality than a hundred op-eds (like this). But we made no connections with it. We missed the “swarm of rage”.

Why?

Because artists are there. Activists are here. Each to our own silo.

I am an activist. I owe my being to others’ dreams of freedom, to the poetry within self-sacrifice, to a shared conviction in the humanity of humanity and the bounties of our planet, a belief that has inspired generations to fight and if necessary die for a better world.

Today, Covid-19 and all that it has laid bare, combined with the gathering climate crisis, has brought us to what the UN Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights, Philip Alston, describes as:

“an existential crossroads involving a pandemic, a deep economic recession, devastating climate change, extreme inequality, and an uprising against racist policies”.

The 99% really do need to unite and realise that despite all our differences and different beliefs there is a way to inhabit the world together. However, this unity will not be achieved through constant evocation of the gods of religion, nor the gods right or left of politics; the revolution will not be catalysed by a turgid discourse. Activists are birth attendants for a new order. Our job is to help people regain consciousness and agency of their own beauty, dignity, shared humanity, and collective possibility.

When they do they will be ready to riot.

And that will depend heavily on our ability to once more see and embrace the poetry in our day-to-day struggles for equality and social justice. DM/MC/ML

Writers’ note: to be most persuasive this essay requires you to listen to, watch and read the links. But do you have the time?! Read Mark Heywood’s Love letter to Social Justice Activists (1) here. Read The Art of Seeing here.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider