Maverick Citizen: Spotlight

What we think we know about the Covid-19 epidemiological numbers

Many of the key epidemiological numbers for Covid-19 are still uncertain. Adele Baleta takes us through some of the best estimates out there.

President Cyril Ramaphosa’s decision to lock down the country was largely based on epidemiological projections. It was projected that if the SARS-CoV-2-19 virus was allowed to spread unchecked to the extent that 40% of people in the country became infected, more than 350,000 people could die.

The National Institute of Communicable Diseases (NICD) has confirmed that these numbers are already outdated and new models are coming up with new numbers that are yet to be announced.

The results of Imperial College London modelling published in mid-March, indicated that more than 500,000 people may die from Covid-19 in the UK and more than 2.2 million in the US if no action were taken. This modelling prompted UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s announcement of new restrictions on people’s movements. Social distancing measures were also introduced in many parts of the US.

Referring to the South African model, Alex Welte, a research professor at the Centre of Excellence for Epidemiological Modelling and Analysis at Stellenbosch University, pointed out that “nobody is expecting an infection rate of 40% at this point”.

“If you put your hands in your lap and do nothing that may plausibly be the case,” he said. “If we look at Wuhan in China, by the time the epidemic has withered away to nothing, the attack rate (infection rate) has been less than 1%.”

The numbers are uncertain and there is a lot of debate about whether mortality estimates are too high or too low. So, what is the right number? The right answers, however, are not what epidemiological models are for.

John Brooks, chief medical officer at the US Centers for Disease Control, said in a webinar recently, epidemiologists increasingly use modelling to better understand where an outbreak may spread. “These types of analyses can help strategically direct and ideally preposition preparedness and response resources.” So, for example, social isolation reduces transmission and slows the spread of the disease. Contact tracing catches people before they infect others.

Model-makers have to work with the data they have. A novel virus such as SARS-CoV-2, has a lot of unknowns, he said. “Although modelling is helpful, the widespread dissemination of infection in our hyper-connected world, as with Covid-19, creates challenges to these kinds of prediction analyses,” said Brooks.

Welte said: “We do not have sufficiently informative data to tell us where we will be in the next four weeks. However, grappling with the data and understanding why it’s not possible to make any robust projection, is telling us what the data is we wish we had.

“The models become more coherent when the data is making sense. Right now, the data is fragmented and confusing but this is giving food for thought for how we can fix this.”

Like the World Health Organisation (WHO), many countries are currently relying on data from China, where the epidemic has matured. More data is coming from Italy and Spain, which have recorded most deaths, but this is likely to be outstripped by the US, which has the highest number of infections.

But much data is not yet settled and many questions remain. As we learn more about the various epidemiological numbers, and specifically about these numbers in the South African context, modelling of the epidemic will become more reliable.

Here are some of the current estimates for some of the key epidemiological numbers:

The incubation period

If we have been to a country with a high number of Covid-19 cases, even if we do not have symptoms, we have to self-isolate for 14 days. The same goes for those who have mild symptoms. This means staying at home and not leaving the house.

But why 14 days exactly?

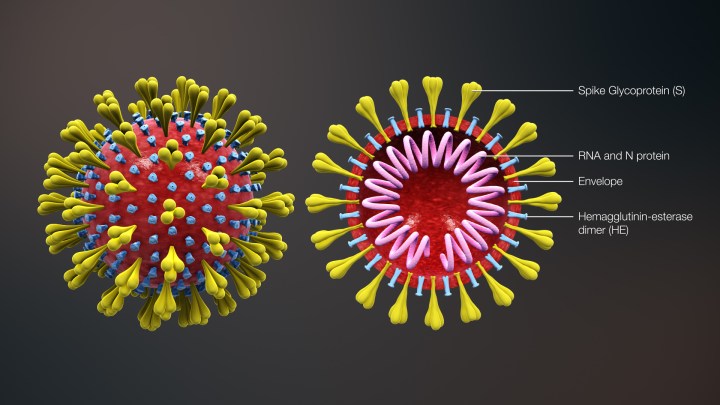

This number is not a thumb suck, but has to do with how viruses invade healthy cells and replicate. The virus relies on replication to be able to survive. Once it infects someone (a host) it takes some time for the virus to make enough copies of itself that the host begins to shed the virus by coughing and sneezing — ensuring new hosts are created. This is the virus’s incubation period.

For us, the hosts, the incubation period is from the time we are exposed to the pathogen to the time the virus becomes detectable in the body, even if we do not have any symptoms. “It is never a fixed period for most pathogens,” said Professor Jeffrey Mphahlele, vice-president for research at the South African Medical Research Council.

For SARS-CoV-2, the mean incubation period is five to six days but the range can be anywhere between two and 14 days, “which is why a 14-day isolation period has been settled on”. “For some people the period could be even longer,” Mphahlele said. About 97% of the people who get infected and develop symptoms do so within 11 to 12 days, and about 99% will do so within 14 days.

If after 14 days the virus is not detected in the body with testing “it’s taken that even if you were exposed to the virus, you were not infected”, said Mphahlele. He pointed out that there is a big open question that makes quarantine recommendations trickier than usual. “It is not yet clear how common it is for people who are infected, but not showing symptoms, to shed the virus.”

You can find some of the key academic articles on the incubation period here and here.

The infectious period

Mphahlele said “we don’t know exactly how long it takes for people to recover from being infectious”. Some estimates in the literature say it can take up to 12 days on average, or more than two weeks, depending on the severity of the disease.

Some of the literature from China (Aylward et al, WHO-China mission) shows that in mild to moderate cases it takes two weeks to recover from viral shedding, which is quick, but six weeks in severe cases, which underscores the need for protective clothing for health workers. Mphahlele added that from the onset of symptoms to death can be up to eight weeks depending on the severity of the disease. “Death comes quicker depending on underlying illness,” he said.

A Lancet Infectious Disease study estimated an average of 18 days from symptom onset to death.

The series interval

The series interval is the time it takes for a second person, who becomes infected, to develop symptoms. So, the shorter the interval, the more contagious the disease and the quicker it can spread through a population. You can think of it as the period of time from when person A transmits the virus to person B, to the point where person B starts showing symptoms and transmitting the virus to person C.

The US Centers for Disease Control estimate this number at 3.96 days, but estimates vary.

The basic reproductive number

Scientists often estimate contagiousness of a disease with a figure called the basic reproductive number, or R0 (pronounced R-nought.) The Covid-19 virus is currently believed to have an R0 of about 3.

“It is a calculation of the degree of ‘spreadability’ or more simply the number of people a sick person can infect on average in a group that is susceptible to the disease (meaning they don’t already have immunity from a vaccine or from previously fighting off the disease),” said Mphahlele.

Crudely speaking, this means that each infected person is likely to spread the virus to three others. This number can, however, be reduced through various measures such as social distancing and isolation of infectious persons. If R0 drops below 1, an epidemic begins to wane.

The case fatality rate

There are a number of different ways to measure the deadliness of Covid-19 and the numbers can differ substantially depending on what kind of fatality rate is being used.

The most widely quoted mortality measure is the case fatality rate (CFR). CFR changes as new data comes in. There is also a high degree of variability from country to country. The CFR is the total number of deaths divided by the total number of officially confirmed cases multiplied by 100, in order to give a percentage. (This is a simplification. See this article for more of the complexities with CFRs in the context of Covid-19.)

Korea is estimated to have a CFR of less than 1% while most other countries with significant outbreaks have reported higher rates. According to the British Medical Journal, as of 2 April, official statistics showed 872 deaths had been recorded in Germany from 73,522 confirmed cases, translating to a fatality rate of 1.2%. This compares with fatality rates of 11.9% in Italy, 9% in Spain, 8.6% in the Netherlands, 8% in the UK and 7.1% in France. WHO director-general Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus previously mentioned a global rate of about 3.4%.

On 13 April, South Africa had 2,272 confirmed cases and 27 confirmed deaths – giving a CFR of around 1.2%. This rate has been rising steadily in recent weeks.

Mphahlele cautioned that this figure only considers confirmed cases but “there are asymptomatic cases and many more mild cases that do not present at hospitals who are not being counted, which would bring the death rate significantly down”. DM/MC

Adele Baleta is an independent science writer, media consultant and facilitator. This article was produced for Spotlight – health journalism in the public interest. Like what you read? Sign up for our newsletter and stay informed.

"Information pertaining to Covid-19, vaccines, how to control the spread of the virus and potential treatments is ever-changing. Under the South African Disaster Management Act Regulation 11(5)(c) it is prohibited to publish information through any medium with the intention to deceive people on government measures to address COVID-19. We are therefore disabling the comment section on this article in order to protect both the commenting member and ourselves from potential liability. Should you have additional information that you think we should know, please email [email protected]"

Become an Insider

Become an Insider