OP-ED

2020 retrospective vision: The next decade will need to bring more than just echoes of ‘Africa rising’

Ten years ago, the hype around Africa’s economic potential was high. A decade later, the continent’s performance can largely be described as ‘one step forward, two steps back’. This is most evident in a decade of democratic backsliding and technological bottlenecks which threaten to leave Africa behind as the Fourth Industrial Revolution gains momentum.

There was no shortage of hype and hope around Africa’s emergence in 2010. Off a global super-cycle, which delivered Africa’s strongest growth decade on record, annual economic growth hovered around 5.5% between 2000 and 2010. In 10 short years, the African narrative had swung from the “hopeless continent” to “Africa rising”.

This remarkable story of linear growth and endless expansion, however, was born from an ill-informed combination of commodity-driven interests, straight-line projections and ballooning demographic trends. Reports like McKinsey’s Lions on the Move in 2010, highlighting Africa’s compelling business opportunities and the rise of the African consumer, fuelled the excitement. Little regard was given to the detail, including a broad range of non-economic issues or contextually relevant nuances across the continent, not to mention shifting global dynamics.

Expectations across the board were high. Interest from around the world surged with European firms reigniting dormant investments, while mining and engineering giants from Brazil to China committed to rail, port and energy projects that guaranteed double-digit growth across the continent. Global brands, such as Walmart, which acquired 51% of South African retailer Massmart in 2011, clamoured to gain a foothold on the continent. All wanted to be a part of the new global frontier, the dawn of the African decade.

But as we enter 2020, the hype has failed to meet the lofty expectations of 2010. In 2020, reflecting on progress over the past decade, what is the reality on the ground today? What strides has the continent made economically, politically and socially over this period of unprecedented interest and opportunity?

Some growth, but erratic performance prevails

Part of the problem in projecting Africa’s performance lies in interpreting it according to the Chinese model of unfettered economic and population growth. The reality is that Africa is part of an international system characterised by a diminishing rate of growth.

In 2007, at the height of the global super-cycle and commodity boom, more than 60 countries worldwide enjoyed economic growth in excess of 7%. By 2017, fewer than 10 economies were growing above 7%. Africa was a part of this story, and has been severely impacted by this downward trend.

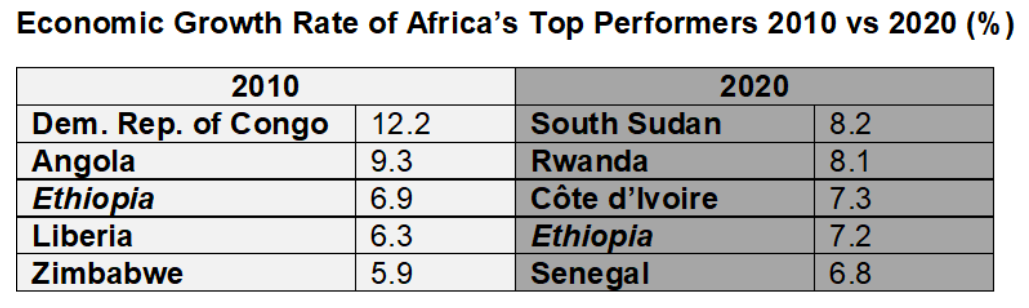

At the start of 2010, Africa’s projected economic growth was 4.5%. Today that projection is 3.5%. In 2010 eight of the 20 fastest-growing economies were African. These included The Republic of the Congo, Angola, Ethiopia, Liberia, Zimbabwe and Uganda, Tanzania and Sudan.

Ten years on, the mix of countries making up the list of high-growth economies is quite different. The fastest-growing African economies in 2020 will be South Sudan, Rwanda, Côte d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Senegal, Benin and Uganda. Interestingly, these African economies appear to be re-establishing pre-2010 rates of growth, which appears to be good news.

Source: IMF Data 2010 and 2020

The star performer between 2010 and 2020 was Ethiopia. The true lion of Africa has averaged 9% growth a year since 2000, making it Africa’s fastest-growing economy over the past 20 years. As the second-most populated country on the continent, with more than 110 million people, this is significant.

South Africa and Nigeria, Africa’s two largest economies, were the gross under-performers over the past decade. Plagued by political uncertainty, corruption and rising unemployment, South Africa and Nigeria account for more than 50% of Africa’s total economic output, but have failed to meet their potential and have dragged down the overall growth of the continent.

Growth disparities and increasing levels of development over the past decade characterise the heterogeneous nature of Africa, where a single Africa rising or falling narrative fails as a description. There is far more to the story than conventional upward and downward economic growth cycles.

Some countries took advantage of the commodity boom by implementing genuine structural changes to encourage greater diversity and industrialisation. This was often coupled with increased connectedness through liberal policies in pursuit of new export markets, or targeting foreign investment and innovative thinking. These industrious African countries have enjoyed sustained levels of growth and broad-based development. Ethiopia is the best example of this.

Those that failed to reform are still trapped in commodity cycles, where 2010 to 2020 was yet another lost decade, characterised by economic stagnation or even regression, at a time where their populations are growing less tolerant in light of the vast African potential.

Rising political risk with democratic failure

Political stability is an undeniable prerequisite for business and economic progress in Africa. Inextricably intertwined, politics remains the primary driver and shaper of context and society, and is the foundation of business confidence.

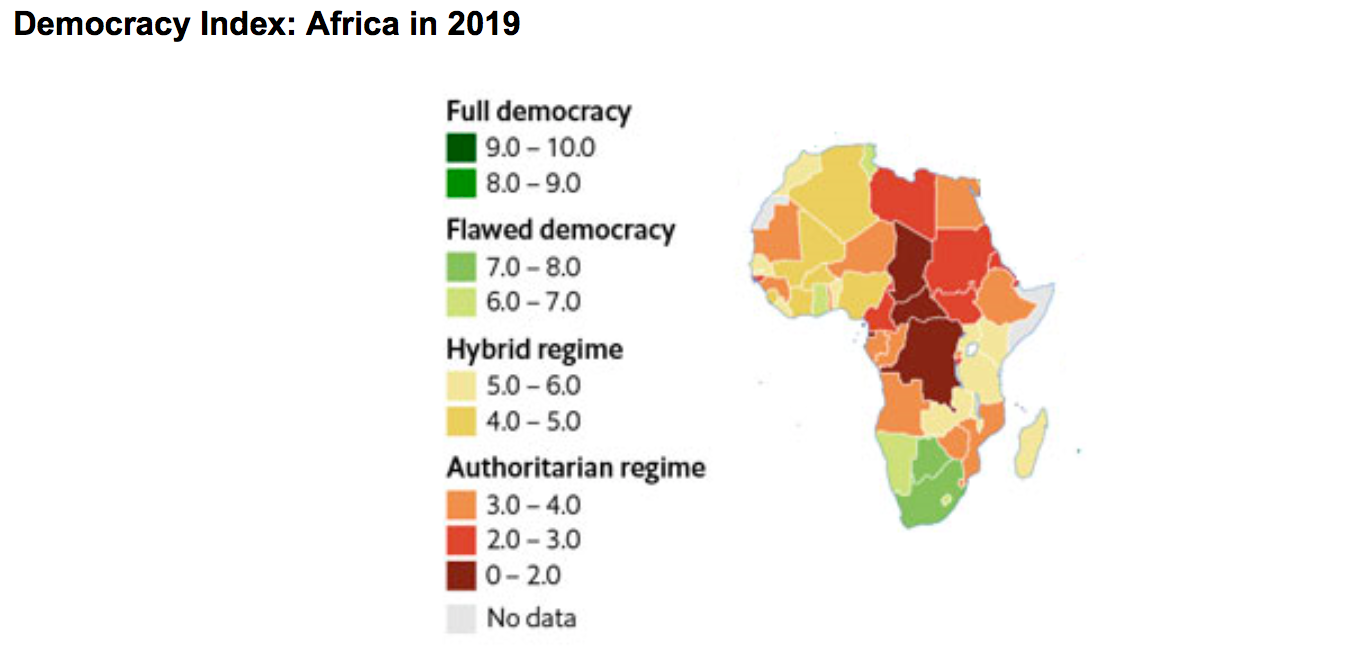

The Economist Intelligence Unit’s (EIU) Democracy Index 2019 found that democracy has failed to improve across Africa over the past decade. The average score for the region fell from 4.36 in 2018 to 4.26 in 2019, the worst score since 2010.

There were some exceptions among the 44 countries measured across sub-Saharan Africa. While 16 African countries improved their score, 24 countries recorded a decline in electoral processes and political pluralism. Between 2010 and 2020 only Mauritius ranked as a “Full Democracy”.

Overall, six sub-Saharan African countries were ranked as “flawed democracies” in 2019. This is a marginal improvement from eight in 2010. But 15 are regarded as “hybrids” or a mix of authoritarian rule and democracy, compared to 10 in 2010. The remaining 22 are classified as authoritarian, a disappointing improvement on 25 in 2010.

Source: The Economist Intelligence Unit, Democracy Index 2019

The results are clear: Creeping authoritarianism and democratic backsliding have characterised the political landscape in Africa over the past decade. This is simply unacceptable at this crucial stage of development.

Promise of regional integration

Economic and social integration is key to Africa’s growth and development. Industries and firms need economies of scale and access to new markets. It is well known that greater openness to trade and investment is one of the reasons behind Africa’s growth since 2000. But despite the obvious benefits, African countries remain by and large disconnected from one another and fail to leverage off the vast potential of the continental collective.

Intra-regional trade in Africa is still the lowest of any region in the world. In 2010, intra-Africa trade was a dismal 10% of total African trade. This figure has risen to 17% in 2019, but is still far from the untapped potential of the continent. While freer movement of trade under the much-anticipated African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) is finally expected to begin on 1 July 2020, a greater focus on tangible connectedness from infrastructure to streamlined border crossings is needed more than grand agreements. These improvements will be a step toward harnessing the promise of a single market of around $3-trillion, beyond the agreements discussed ad nauseam since 2010.

Digitalisation and mobile connectivity

The ubiquitous mobile phone has been the greatest driver of connectedness and African modernisation and is the symbol of the progress made since 2010. This is most evident in the rapid adoption and pervasive spread of smartphones, which have enabled internet penetration and transactional connectivity deep into the furthest corners of the continent.

Over the past decade, mobile internet subscribers quadrupled and sim connections reached more than one billion, with more than 80% penetration. There are an estimated 600 million smartphones in circulation across the continent, driving down the cost of data to a fraction of what it was in 2010. Meanwhile, technology development in Africa is booming. WeeTracker estimates that $1.3-billion was invested in tech start-ups in Africa during 2019, the most successful year to date.

But Africa still lags behind other digital economies around the world. The continent’s level of internet bandwidth used represents just 1% of the world’s total. Less than 10% of African households subscribe to high-speed internet services. And despite the mobile revolution, just one-quarter of Africans have access to the internet.

Digital aspirations aside, basic needs from the previous industrial revolution remain a challenge. Africa’s severe infrastructure deficit continues to be a problem. More than 600 million people across the continent are still living without electricity in their homes.

There is an urgent need to provide the basics while, at the same time, the need for deeper investments in the digital economy for Africa to keep pace and avoid falling further behind the rest of the world, yet again.

Demographics and urbanisation

Home to one billion people in 2010, Africa’s current population is around 1.3 billion people. This number is expected to breach 1.6 billion by 2030, and 2.4 billion by 2050.

According to the World Bank, the share of Africans living in urban areas in 2010 was 36%, and Cairo was the most populated city. Today Africa has become an urban continent, with about 45% of the population living in cities. The largest city in Africa is now Lagos, home to more than 21 million people. While five out of the 10 most populous countries in the world in 2020 are in Asia, in 2100, five African countries – Nigeria, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Egypt and the Democratic Republic of the Congo – are expected to be among the world’s 10 largest.

Africa’s unique demographic profile of a large and growing population under the age of 20, combined with rapid urbanisation and the projected growth of cities, was described as a “demographic dividend” in 2010. This is increasingly a demographic nightmare as population growth and urbanisation have placed additional strain on job creation, education, basic infrastructure and sanitation.

Tanzania and Zambia have both experienced a 35% surge in population growth over the past 10 years, accelerating cycles of poverty, most pervasive in rural areas. Sustainable development requires deeper consideration as politics and policy have not kept pace with population growth and migration. Urgent reforms and innovations need to be implemented to avoid a sure catastrophe.

One step forward, two steps back

Looking back over the last decade, Africa’s performance can largely be described as “one step forward, two steps back”. This is most evident in the region’s democratic backsliding over the past 10 years, and prevailing technological bottlenecks which threaten to leave the continent behind as the Fourth Industrial Revolution gains increasing momentum.

As we enter a new decade, the hype and hope for Africa from 2010 lingers. For a continent boasting the youngest population in the world, but with a grossly uneven track record of development over the past decade, Africa has reached a tipping point.

Bold action must be taken. Innovative solutions, which consider the nuances of the African landscape, need to be implemented. These must be based on a decisive shift in thinking if Africa is to forge a new path to prosperity toward 2030. DM

Professor Lyal White is senior director of the Johannesburg Business School (JBS) at the University of Johannesburg, Liezl Rees is head of the Centre for African Business (CAB) at JBS. and Nikitta Hahn is researcher for the CAB.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider