The South African economy has been on a slippery slope for more than a decade. Stagnant economic and employment growth in a context of high inequality and poverty serves to deepen divisions in society. In the 2000s SA was building its economic capacity but that has unravelled over the past decade.

The budget is meant to be the clearest expression of the state’s plans for resource allocation. Did the Budget 2020 give hope for a reversal of this slide?

Success would not require austerity. Nor should it have sought to be a Keynesian-type stimulus package. These are static short term measures that cannot solve South Africa’s structural challenges. Mboweni had to offer a pathway to fiscal sustainability. This requires clarity, consistency and a real commitment to big choices that lead to progressive improvements to deepen revenue collection and public spending impact.

Economists debating Budget 2020 seem polarized around whether the budget needs to impose austerity or expansion. For some, austerity is the way back to health: for them, fiscal expansion is impossible since the state must at least halt deficit growth by cutting R150-billion out of the budget. Others say austerity has already caused slow growth and falling living standards: they believe the budget should be expansionary funded through rising taxes or borrowing.

The idea that SA has been in austerity confuses me. Austerity means different things to different people. But I don’t think it ever means government spending that grows in line with GDP, nor does it involve rising deficits.

If SA was being starved by austerity, you would know it.

In Greece austerity looked like a dramatic cut-back in public sector employment, salaries and benefits, cuts to minimum wages, reduced pension payments, widespread privatization of public enterprises, and dramatically rising taxes. Over the course of seven years, a toe dipped in the austerity water was hit by a tsunami wave. Greece may be able to repay its loans now, but unemployment rose to a high of 27%, 300,000 people left the country seeking work and the black market now accounts for about 20% of the economy as firms seek to evade taxes.

A 2017 UNCTAD report reviews the pernicious impact that austerity policies can have on poverty, especially in developing country contexts.

The SA government is not bankrupt, but potential sources of capital have a diminishing belief in future ability to repay loans. If the SA economic trajectory continues, a Greece-like failure to pay bondholders is a real possibility. Anyone who cares about living standards will ensure this does not happen.

Clarity on SA’s financial pathway is the main concern. Credit rating agencies could likely live with rising debt if it were contributing to growth and the building of SA’s human and capital endowments. This would create confidence that loans could be repaid in future.

Contradictory messaging across Government, poor spending habits and weakened governance of key entities can easily create concern about the future.

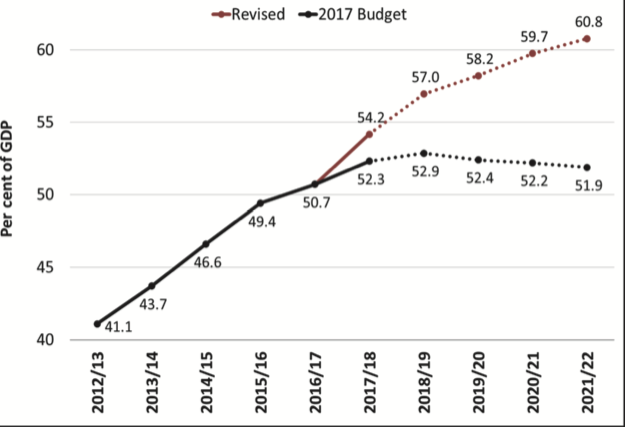

Treasury first raised a red flag in the 2017 Medium Term Budget Policy Statement with concern that the debt-to-GDP ratio could not be predicted with any certainty, saying it could be 51.9% or it could be 60.8%, depending mostly on domestic risks especially those related to SOEs. The 2019 Medium Term Budget Policy Statement sees the debt-to-GDP ratio potentially continuing to rise to 80.9% by 2028. This budget aims to short-circuit runaway debt in a way that also sustains spending on critical programmes. The 2020 Budget sees the debt-to-GDP ratio rising to 71.6% by 2022/23.

South Africa’s economy is highly susceptible to global shocks. These include black swans like coronavirus or a global financial crisis and grey rhinos like commodity cycles. The major uncertainties should not be caused by factors under domestic control.

The transformation agenda in SA aimed at achieving full employment and poverty eradication will depend on a sustainable flow of public funds over generations to come.

Most of the domestic risks that Treasury predicted have surfaced. The ability to protect public finances from global shocks over which SA does not exert influence is diminishing.

The budget definitely needs to be stimulatory. Improving the quality of public spending should not be underestimated as an economic stimulus. There is significant evidence of under-spending on infrastructure. There is also considerable spending that does not build capacity as intended. This suggests that there is potential to stimulate growth and employment by the SA state spent existing budgets more effectively.

Essentially, the budget re-allocates spending and cuts R156-billion in non-interest spending over three years. This results in non-interest spending sitting flat with an average nominal growth of 4.1% annually to 2023/24.

A growth path requires continuous improvement in tax collection rates, public sector efficiency and service delivery per Rand spent. It must enable the rebuilding of capacity. Does the 2020 budget offer that guidance?

Three priorities will define the pathway to financial stability

The public personnel aligned to service delivery

Public personnel costs is the main target for cuts because civil servants’ salaries have grown by about 40% in real terms over the past 12 years, without equivalent increases in productivity”. R160-billion is meant to be cut, incrementally reduced by R37.8-billion in the current financial year, R54.9-billion in 2021/22 and R67.5 billion in 2022/23.

This could apparently be done through a “combination of modifications to cost-of-living adjustments, pay progression and other benefits”.

The three-year public sector agreement on salaries and conditions of service ends March 2021. Public sector negotiations tend to be framed too close to the time that an agreement is needed.

A clearer, longer-term strategy is needed to ultimately balance the trilemma of budget constraints, employment growth needed for service delivery and public sector performance.

This should be aimed at sustainable remuneration, better grading that enables staff to enter at the bottom layers, staffing structures aligned to delivery, and performance-linked benefits.

At a minimum, the next agreement would attend to automatic 1.5% annual increments, a reduction in bureaucratic staff and an expansion in service delivery personnel and support staff, the appointment of suitably qualified personnel especially in leadership positions such as principals in schools, municipal managers, and SOE leadership.

Where staff need upgrading to achieve required standards they should have support but also there should be a three-year cut-off. Lifting “productivity” will require significant improvements in human resource management.

Improve the quality of spending in infrastructure delivery

Infrastructure spending stimulates the economy and creates jobs. It lays the foundation for growth and development. This is a critical lever in Government’s arsenal.

Growth projections have been reduced by 0.3% due to electricity shortages. Actively stimulating private investment in generation would be a big growth stimulator. The proposals currently involve procuring electricity from independent power producers, allowing municipalities to procure power from the private sector and enabling self-generation.

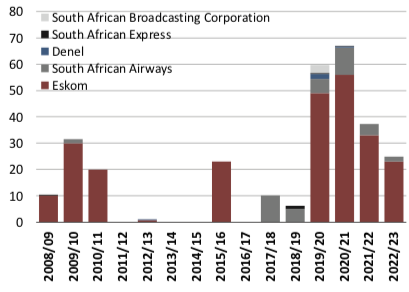

The Treasury seeks to “contain financial demands from distressed state-owned companies, which now crowd out other budget items. R 60.1-billion is reallocated to Eskom and South African Airways.

The reallocation of funds to Eskom and SAA will help course correct the economy if they fuel entity reforms. If Eskom and SAA don’t start taking a new dynamic shape, these bail-outs could continue.

Financial support to state-owned companies (R-billion)

There is already a budget of R 815-billion in the three-year Medium Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF) for public infrastructure across the spheres of government. In 2018/19, only 80% of infrastructure budgets were spent. Over the period from 2015/16 to 2017/18, the shortfall in spending accounted for 10%, 12%, 16%, 20% 23% of budgets for human settlements, other social infrastructure, energy, water and sanitation and transport and logistics, respectively.

There have been poor returns to infrastructure spending, as seen in a range of infrastructure SOEs. For example, returns on public spending for commuter transport services are extremely low and deteriorating. Public spending has favoured rail with capital and operating subsidies over other modes of transport, without imposing performance and accountability. About 2/3 of public spending on urban transport goes to PRASA, accounting for only 17% of trips. Over the past decade, there were four turnaround strategies, R80-billion in capital subsidies and about R10-billion in operating subsidy annually. Yet performance fell dramatically especially since 2015, causing a 60% drop in Metrorail customers and a 90% fall in long-distance rail passengers. Only half the PRASA coaches are in operation.

Ensuring budgets are spent, and spent well, will offer a significant economic boost.

There has been a hollowing out of state capacity to design, procure, and manage large infrastructure projects. The Treasury has established a Budget Facility for Infrastructure for the purpose of ramping up spending on water, transport and energy infrastructure.

More openness to private sector participation and partnerships will be critical to success. At one end of the spectrum, Government is increasingly working with Multi-lateral Banks, Development Finance Institutions and commercial banks to harness existing credit facilities, technical know-how and oversight to help under-leveraged parts of the public sector (specifically metros) to ramp up spending on water, transport and energy infrastructure. At the other end of the spectrum, significant growth will be stimulated by the creation of competition in energy generation.

Lifting revenue collection efforts

Revenue collection is the main fuel for redistribution, service delivery and infrastructure investment. Where collection deteriorates, attention is needed to restore tax to optimal levels. It is far better to strengthen tax collection than to raise tax rates. Raising taxes takes money away from those who are committed to tax morality. It, therefore, fines those that pay, to the benefit of avoiders. Raising income and corporate taxes, on the other hand, encourages tax avoidance and can inadvertently result in reduced receipts.

While many analysts were expecting VAT increases, Mboweni surprised with reductions in personal tax, especially for middle-class workers.

The rate of tax collection at any rate of GDP growth (or tax buoyancy ratio) has fallen over time. The long-run tax buoyancy ratio is about 1.1, but has fallen to 0.93.

The appointment of Edward Kieswetter as the Commissioner of Revenue Services is one of the single most important steps taken in 2019. It is a significant and hopeful sign of a return to financial health. Kieswetter is a seasoned business leader and has experience at an executive level in SARS. He is moving fast to restore capability, and this speaks to an enabling environment created by Mboweni. It is surprising that more commentators have not kept an eye on this important development.

Mboweni’s Budget 2020 guides us to a possible path out of spiralling debt toward financial sustainability. Its success depends largely on the commitment of his cabinet colleagues. The Finance Minister does not act alone. Building leadership capacity in key locations in the state will need to be the top priority. BM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider