BUSINESS MAVERICK: OP-ED

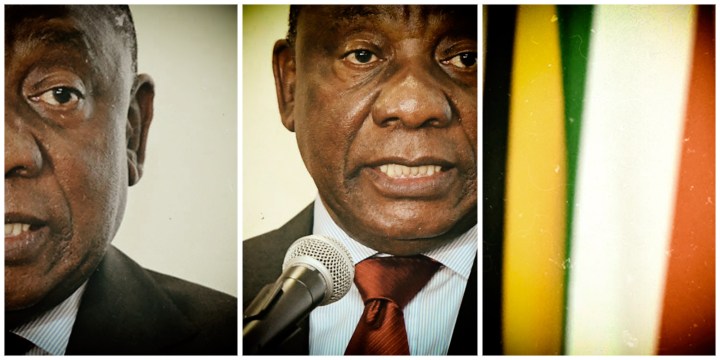

Will Ramaphosa’s weekly missive hit the mark?

The tide has turned somewhat negatively for President Cyril Ramaphosa — the national mood is getting sombre. Three weeks ago, he announced a new communications channel — a weekly English-only e-letter from the president to ‘fellow South Africans’. It’s hard to say what this hopes to achieve, given the high levels of illiteracy and the criminally high cost of data in SA.

Soon after its unbanning and the release of its leaders from prison, the African National Congress was faced with two tasks: first, to win via multi-party talks what it could not win through the armed struggle — a negotiated end to apartheid; and second, to simultaneously get its message across to millions of South Africans who had been deprived of its voice through censorship attached to the ban.

The results of the first task are evident today — namely, our rowdy 25-year-old constitutional democracy and its unfinished business such as the failure to roll out a credible land reform programme and to get better outcomes from the billions five successive ANC-led governments spend each year on basic education.

The results of the second task are hard to see. The party is still complaining about its messages being distorted and ignored by the so-called mainstream media. The struggle to get its message across continues, complicated by the normalisation of fake news.

Before the all-race elections of 1994, under Nelson Mandela, the ANC appointed its then head of information and publicity Pallo Jordan and veteran journalist and now businessman Moeletsi Mbeki to scour the world looking for funds to set up an ANC-friendly newspaper. This mission would take the pair to the offices of Tiny Rowland, the late British newspaper baron and owner of the Lonrho mining conglomerate, and Moshood Abiola, the Nigerian businessman who won his country’s elections but was never allowed to assume high office.

Promises were made, but the project failed to take off. Quite sensibly, when Mandela led the ANC to power in 1994, he dumped the project. It would be inappropriate, he reasoned. Still, the mainstream press continued to get it wrong, complained the party. And the mainly donor-funded alternative media died alongside formalised apartheid.

Frustrated at the ongoing misrepresentation, Thabo Mbeki, Mandela’s successor, started penning a presidential letter to members, circulated via the internet and picked up religiously by newspapers such as Sowetan, which was sympathetic to the ANC despite its heavy Black Consciousness leaning.

Mbeki wrote the letter, sometimes a strident polemic, until his ousting from office in September 2008 by forces loyal to his successor and rival Jacob Zuma. Using his position as ANC president — instead of as leader of the republic — enabled Mbeki to deal decisively with his perceived detractors without entangling government. Two examples spring to mind: first, a missive against Tony Trahar, then CEO of Anglo American; and second, an intemperate attack on Anglican Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu.

If memory serves, Zuma, who came to power supposedly as the man of the people, may have ‘written’ one or two of the letters before discontinuing the practice.

A few years later into his presidency of the ANC and the republic, he helped his friends — the Gupta family — to set up a media house to tell the good-news story.

First, Infinity Media, the Gupta vehicle that housed their media interests, established The New Age, the broadsheet daily paper; and months later they set up 24-hour news channel, ANN7. Testimony before the Zondo commission of inquiry into State Capture has revealed the extent of Zuma’s personal involvement in both projects.

As well as providing training grounds for young journalists, it would be no exaggeration to suggest that the Gupta media provided a friendly voice to the Zuma administration and the dominant faction of the ANC at the time.

Zuma is out. The Guptas have left the country and their media house collapsed a year ago, strangled as commercial banks closed their accounts.

Up until recently, Zuma’s successor President Cyril Ramaphosa has enjoyed good press, on the back of his Thuma Mina and New Dawn campaign — a mixture of spin, charm offensive and anti-corruption campaign.

But the tide has turned somewhat negative. Despite his achievements, including numerous anti-graft commissions, summits (on gender violence, investment and jobs) and institutional reforms, the national mood is getting sombre. During the first quarter of 2019, load shedding shrank the economy by more than 3% and a jobs bloodbath is underway, deepening the crisis of youth unemployment.

In September 2019, violence broke out in several parts of the country, forcing countries such as Nigeria to evacuate some of their nationals from SA. A surge in the numbers of women and kids being brutally murdered and assaulted has caused anger across the country.

The National Treasury has released a discussion document, elaborating measures that — if implemented — could lift the GDP growth from 0.5% to 3%. A special appropriations bill has been tabled in Parliament, providing a financial lifeline to debt-ridden Eskom, alongside billions worth of bailouts to other state-owned enterprises. Surprisingly, Moody’s has not downgraded SA.

The mini-budget policy statement, an annual update, has been delayed to the end of October 2019, and Ramaphosa skipped the annual United Nations General Assembly in September to focus on the domestic agenda.

Three weeks ago, he announced a new communications channel — a weekly e-letter from the president (of the republic) to “fellow South Africans”. The first letter read like a mini-state of the nation address. The second read more like a diary, chronicling his meeting with Muhammadu Buhari, his Nigerian counterpart, who undertook a low-key state visit a week ago. He used this as a platform to denounce xenophobia and extol the virtues of intra-African trade and investment.

This week’s letter was about the measures undertaken to reduce the cost of doing business — data, energy, port, immigration regulation and transport charges — and came on the back of his address to the Financial Times annual Africa conference and the release of the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report. The latter showed an improvement of eight places in SA’s ranking on the index. He also spoke about his second investment conference, which is part of his drive to recruit R1.2-trillion in foreign direct investment to SA by 2023.

It’s hard to say what the Ramaphosa presidency hopes to achieve with these weekly English-only e-letters. This is especially an issue given the high levels of illiteracy and criminally high cost of data in SA. Assuming the intention is to communicate the work of his administration, it’s unclear why he’s not using his multilingualism (a rare strength) — and the public broadcaster — to reach millions of far-flung poor South Africans in between elections.

What’s known, however, is that leaders — politicians and business executives alike — are frustrated by supposed distortions of their messages by the media (especially print, which is facing multiple challenges). Few ever get it right in communicating their messages effectively and efficiently to the populace. This short list includes Tony Blair, Bill Clinton, Barack Obama and, perversely yes, Donald Trump.

Blair and Clinton kept the beast occupied by feeding it constantly through trusted lieutenants such as Alastair Campbell (Blair’s press secretary) and Mike McCurry and Dee Dee Myers (Clinton’s press secretaries). Trump went through several press secretaries before realising what the problem was: himself, not the message or messenger.

The White House briefings have since stopped. Instead, Trump now grants unscripted long, rambling media briefings when travelling, about anything and everything under the sun. TV interviews are only reserved for his acolytes at Fox News.

The print and electronic media, which he derisively calls fake news, relies on anonymous sources who are as frustrated by Trump’s cavalier attachment to reality and facts.

As for the rest of the world, including America’s allies and foes, his phone — especially his Twitter account — remains his preferred means of communication. His tweets allow him to bypass the media and reach out directly to his intended audiences. Of course, it helps that English is the dominant language.

Among corporate executives, Jack Welch got it right by prioritising internal communication with employees. This story is contained in an excellent book by his long-term speechwriter Bill Lane, Jacked Up: The Inside Story of How Jack Welch Talked GE into Becoming the World’s Greatest Company.

Obama relied on three key assets: the supremacy and power of facts, his world-class oratorical skills and a great team of aides. After Martin Luther King Jr, Abraham Lincoln and JF Kennedy, he elevated speeches to an art form and a powerful tool of communication.

Soon after taking office, he set up the Office of Presidential Correspondence (OPC) to handle millions of letters from ordinary Americans. According to a new book on his presidency, To Obama, A People’s History by Jeanne Marie Laskas, of the thousands of letters received each day by the OPC, Obama insisted on reading — and sometimes responding to — 10 each day.

Why bother to read 10 letters a day when there’s an army of officials and algorithms that could do it? Here’s what Obama says:

“By the time I got to the White House and somebody informed me that we were going to get 40,000 or whatever it was pieces of mail a day… I was trying to figure out, how do I in some way duplicate that experience I had during the campaign?

“Ten a day is what I figured I could do. It was a small gesture, I thought, at least to resist the bubble. It was a way for me to, every day, remember that what I was doing was not about me. It wasn’t about the Washington calculus. It wasn’t about the political scoreboard. It was about the people who were out there living their lives who were either looking for some help or angry about how I was screwing something up.

“And I, maybe, didn’t understand when I first started the practice how meaningful it would end up being to me.”

Laskas sums up the message of the preceding paragraph from Obama thus:

“Mail was important” — to everyone, “from the lowest-ranking staffer working the scanners over in the EEOB (Eisenhower Executive Office Building) to speechwriters, policymakers, and senior advisers in the West Wing.”

Obama’s message to other presidents is quite instructive.

First, there’s no manual for being president. Second, once in power, you’re surrounded by many people (from bodyguards to assistants to speechwriters and researchers) who, inadvertently, shelter you from the reality of those you lead. Third, it is vitally important to focus on the needs of the populace instead of the palace politics (whose calendar is driven by self-interest and the next election) and, the letters from Americans ensured that his communication — through speeches and interviews — remained as fresh, relevant and humble as it was during the campaign.

That is Ramaphosa’s challenge: ensuring the message from his morning walks, Thuma Mina and New Dawn campaign mantra remain fresh, genuine and relevant through his presidential communication. BM