Business Maverick

Inside the acrimonious Vodacom Please Call Me settlement talks

Nkosana Makate, the inventor of Please Call Me, wants a settlement of more than R10-billion. Vodacom is prepared to settle at R47-million. Settlement talks have broken-down (again) as both parties are heading back to court. This adds another twist to a battle that began more than 10 years ago.

Three years after the Constitutional Court affirmed that Nkosana Makate is the inventor of Please Call Me, forcing Vodacom to enter compensation talks with him, both parties are still in a tug-of-war about what constitutes a fair settlement.

Since the top court ruled in favour of Makate on April 2016 — in a dispute spanning more than a decade — the telecommunications giant has offered him two compensation amounts (disclosed publicly).

Vodacom initially offered Makate R10-million, which was based on the salary paid to former Group CEO Alan Knott-Craig Sr in 2001, when the company launched Please Call Me, and adjusted for the time value of money, a concept known to consider inflation or interest earned over a certain period on claims. Makate rejected this offer.

In the latest settlement talks, Vodacom Group CEO Shameel Joosub sweetened the offer to R47-million on 9 January, which Makate has rejected. Makate is now heading to the Pretoria High Court to challenge the offer and have it set aside because it is “inherently unfair.”

Makate invented Please Call Me when he was a trainee accountant at Vodacom in November 2001. The invention was born out of his communication difficulties with his then long-distance girlfriend (now wife) because they couldn’t afford airtime. This gave rise to Please Call Me, which enables a user without airtime to send a text to be called back by another subscriber.

During this time, Joosub was the MD of Vodacom Service Provider Company, the company’s business unit that offers cellular services.

In Makate’s 58-page court application, he included a report by Joosub that outlines “reasonable compensation” and technical methodologies used by Vodacom to reach its R47-million offer. In the report, Joosub said Makate and his legal team proposed a settlement figure of R20.2-billion, which excludes interest. This figure is equivalent to nearly double Vodacom’s cash and cash equivalents (cash on hand and assets that can be immediately converted into cash) for its 2019 financial year of R11.06-billion.

Joosub described Makate’s desired compensation as “unrealistic” because he relied on “incorrect” revenue estimates of the amount the service allegedly generated for Vodacom over the past 18 years. (Joosub’s involvement in settlement talks is part of the Constitutional Court’s order that enabled him to arbitrate negotiations after a deadlock on compensation materialised after the court’s judgment.)

Heated settlement talks

Makate’s papers reveal that settlement talks have been acrimonious. In court papers, Makate said Vodacom’s team of lawyers left a “sour taste” during settlement talks. The company’s lawyers allegedly told Makate that the amount payable to him for Please Call Me would be “zero euros, zero dollars, zero anything”.

Now Makate is asking the court to force Vodacom to open its financial books and disclose the revenue the company has generated from Please Call Me since its launch in March 2001.

Makate’s legal team have forecast that Please Call Me will have earned Vodacom R205-billion in call revenue from 2001 to 2020. This figure excludes advertising revenue linked to the innovation, Please Recharge Me (a service similar to Please Call Me, but the sender asks another subscriber to buy them airtime) and a R4.1-billion contingent liability on Makate’s Please Call Me claim that was disclosed by Vodacom’s parent company, Vodafone Group, to shareholders in its 2017 financial statements.

Makate also wants the court to order that he is entitled to be paid 5% of total revenue that Please Call Me (R205-billion) has generated from March 2001, plus accrued interest and all the legal fees incurred by him since the Constitutional Court judgment. Without interest and legal fees, Makate’s settlement comes to R10.2-billion.

Considering the R47-million settlement that Vodacom offered, Makate said it “sounds like a significant sum of money”. However, “it is in fact merely 0.023%” of the R205-billion call revenue Vodacom allegedly generated from 2001.“There is no sense in which an amount of 0.023% can be said to be a reasonable share of the revenue concerned, which can be up to 85%, as in other instances,” he said.

Makate is vexed because Joosub “incorrectly” based the R47-million settlement on revenue generated by Please Call Me over five years, even though the service “has generated revenue for 18 years and continues to do so”. When Vodacom went to market with Please Call Me, he had an agreement with the company that there would a share of the revenue in perpetuity — “that is for as long as it (Please Call Me) continued to generate material revenue.”

Joosub dug in his heels, saying Please Call Me was never patented, thus using a duration of nearly 20 years to determine compensation is “unrealistic”.

“It seems to me quite wrong to determine the duration of the revenue share by reference to something which was not required, or contemplated, under the contract, which neither party was obliged to undertake, and which neither party thought to register.”

No Please Call Me revenue

Another contentious point is that Vodacom claimed that it makes no revenue from Please Call Me and is unable to calculate revenues generated by the innovation. Joosub said the mobile voice revenue generated by Please Call Me for Vodacom since 2001 is not a direct result of the service, but the company’s investments in its network that increased its coverage, growth in customer numbers and growth in mobile services spending by existing customers.

He added that after Please Call Me launched in 2001, Vodacom’s average revenue per user/customer (Arpu) — a key industry metric — from its prepaid offering, fell from R98 in 2001 to R69 — indicating that “growth in mobile voice revenue could not be directly as a result of Please Call Me only”.

He added that Makate’s compensation model was flawed because it used incorrect figures — not the number of Please Call Me messages sent, but the confirmation message sent to the original sender of the message, wrong average call duration, and incremental revenue that shouldn’t include customers that didn’t increase their airtime spend.

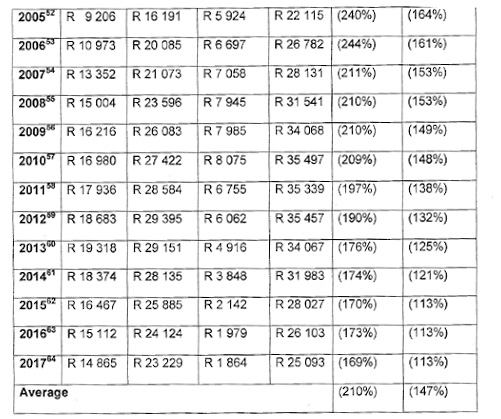

Joosub said this resulted in a substantial difference in figures between Vodacom’s own total mobile voice revenue and Makate’s figures about Please Call Me revenue (see table below).

Source: Joosub’s compensation report.

Joosub said it would be “impossible” to determine “with any reasonable accuracy” whether a call made after the receipt of the Please Call Me was “in fact prompted by the Please Call Me” message. This is important to determine the possible Please Call Me revenue.

However, Makate disagrees:

“Even if the revenue figure could not be calculated with perfect precision, logic dictates that the closer the proximity between the Please Call Me message and the returned call, the stronger likelihood that the call was generated by the Please Call Me.”

About Vodacom’s claim that it cannot determine Please Call Me revenue, Makate said it is “merely a strategy to perpetuate the long-standing fraud” against him. He accused Vodacom of understating its revenue figures by 200% as they “exclude” contract customer subscriptions and mobile termination rates (the prices operators may charge each other to carry calls between their networks (see table below).

Source: Makate’s court papers.

He said the understatement in revenues will increase the R47-million Please Call Me settlement that he was offered by Joosub to approximately R130-million.

In reaching the R47-million, Joosub proposed four settlement models. These include a looking-forward model from 2001, which is based on information undertaken before Please Call Me was launched (Joosub reached a settlement of R51.5-million); an employee reward model (R21.8-million); Time Window Lock Model, which focuses on prepaid and top-up customers who were out of airtime (R38.1-million); and revenue share model (R42.2-million).

Joosub then averaged the two highest figures to reach the R47-million. Makate said Joosub should have confined himself to the revenue share model, but including Please Call Me revenues over the past 18 years plus interest and legal costs. Vodacom said it will oppose Makate’s high court application. BM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider