BUSINESS MAVERICK

Sovereign wealth funds — and adventures in the margin of error

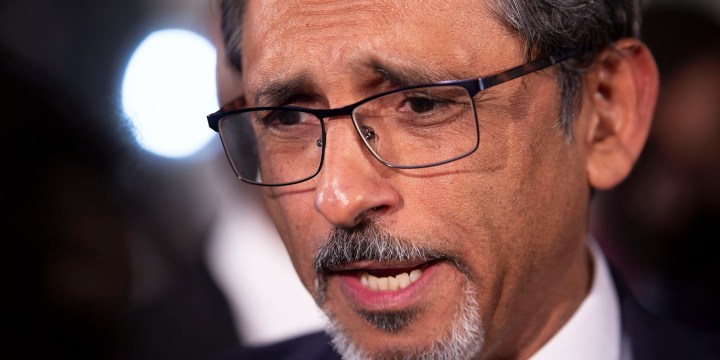

One of the hardest things in life is changing your mind; it’s embarrassing. But after some soul-searching, I have managed the supreme task of actually changing my mind on at least one thing, and that is whether SA should establish a sovereign wealth fund. That means I’m now on the opposite side of conventional wisdom, and on the same side as (shock, horror) Trade and Industry minister Ebrahim Patel and the EFF. But... I could be wrong about being wrong.

In 2010, New Yorker staff writer Kathryn Schultz wrote an unexpectedly popular book about the glory of being mistaken, called Being Wrong: Adventures in the Margin of Error. Her thesis, briefly, is that we are schooled from very young to think that people who don’t agree with us are either stupid or they have the right information but they don’t believe it for some reason.

But, she says, being wrong and realising it, and changing your mind is very much part of the process of being alive.

“This attachment to our own rightness keeps us from preventing mistakes when we absolutely need to and causes us to treat each other terribly,” she said in a TED talk at the time. More than that, trying things out, things turning out differently, and changing, is “ the source and root of all of our productivity and creativity”.

So, in that spirit, let’s apply the principle to the idea of sovereign wealth funds. Trade and Industry Minister Ebrahim Patel raised the idea during his response to the State of the Nation Address, but it was first broached at least eight years ago and has been consistently supported by the EFF.

Patel’s argument is the conventional one: that resource-based economies such as SA face the challenge of the boom and bust commodity cycle, which is a threat to employment during the bust cycles. Some resource-based economies have found a way of balancing that cycle using sovereign wealth funds to absorb the higher rents during the boom part of the cycle.

“When is the right time to do it? You can’t do it when the boom starts. You’ve got to put in place your legal and institutional arrangements,” Patel said at the time.

Business Day subsequently commented with great perspicuity on Patel’s idea, reflecting the conventional economic view, but adding the additional insight that Patel was indulging in a kind of economic fantasy instead of getting down to the real job at hand.

“Talk of sovereign wealth funds, while we should be rolling up our sleeves and boosting our economy, just adds to the impression of a government that’s short of ideas. Action, not fantasy, is what’s needed,” Business Day wrote.

You can see where this critique comes from. Sovereign wealth funds are something of a dreamy state for countries that want to spend more, but have no actual ready cash. That would be us. They are designed to solve the problem of a flood of excess income, which tends to boost the currency, which in turn weakens manufacturing, which then cripples the country when commodities go down.

Oh great heavens above, were it that South Africa, dear land, were in such a wonderful state. As it happens, SA is haemorrhaging cash, mainly because in the public sector, the government has been spending badly mainly on consumption items and doing so at a rate massively larger than it brings in. And in the private sector, South African companies are simply despairing about local growth and are trying to find that growth, not very successfully it turns out, outside the country’s borders. If ever there was a country which is in no immediate danger of being flooded with excess funds, it is South Africa in 2019.

So in the face of these seemingly irresistible arguments, what can you possibly say in favour of starting a sovereign wealth fund? At the outset, I should say my argument is different from Patel’s left-wing fantasy, in which the country is showered with foreign money from its copious resource rents, which it in turn showers on the grateful population who vote ANC for ever and ever, amen.

In fact, it starts from the opposite premise; not from SA’s particular position in the global economy, but the state of the global economy and SA’s position in it. I’m very indebted here to Professor of Economics at the University of Warwick Roger Farmer, who wrote this article for Project Syndicate published by Business Maverick. I think Farmer’s insight is profound, and it’s essentially rooted in this question: Why is the yield difference between bond markets and stock markets not more effectively arbitraged?

At the moment, global bond markets are returning pretty close to nothing. In some cases, investors are actually paying governments for the pleasure of holding their debt. Stock markets, on the other hand, are booming around the world.

Conventionally, the argument is simply that the stock markets are riskier, so investors deserve a yield bonus. But this difference between the bond market’s “risk-free rate” and stock market returns are currently very wide. Over the long term, Farmer cites one study of a century’s worth of data from 16 advanced economies, where the return from investing in stocks was 6.96% higher, on average, than the return on government bonds.

Why is there this gap? Farmer’s explanation is intriguing. He argues there is a missing buyer in the market — the unborn. Because the unborn cannot by definition participate in financial markets, the incentive to arbitrage the difference is diminished. The stock market is dominated by people saving for their retirements, not the unborn, saving for a life not yet created. Although future generations are not yet around to trade in the asset markets, national treasuries can trade on their behalf, he says.

Now, let’s indulge in a fantasy of our own: apply this logic to SA’s “lost decade”. Let’s assume that instead of borrowing R1.4-trillion over the past decade with no noticeable improvement in the economy, the government borrowed that amount and invested it on global stock markets. What would have happened?

To get to the R1.4-trillion, just to make things simple, let’s assume government borrowed R140-billion every year for a decade and put it into a sovereign wealth fund outside government’s control and invested in global stock markets returning 6.5%. In the first year, it would hurt; the government would only get a return of R90-million or so.

But by year 10 it would be earning about R900-billion every year, such are the wonders of compounded returns. That’s about three times as much as the government spends paying off its debt every year at the moment. Instead of money going out, that would be coming in. It would mean every social pension paid by the government at the moment could double.

Miracle!

There are lots of things potentially wrong with this argument. The most obvious is that, in SA, as it happens, investing in the bond market over the past five years would probably have earned more than investing on the JSE. So much for the stock market/bond market yield difference. But historically, the opposite has more often been the case.

In the larger scheme of things, if all governments embarked on this strategy in a sustained way, the yield difference might disappear pretty fast. It’s unlikely, but it could happen. And how do you protect the investment from politics and politicians who always have their beady eyes on any available cash pile?

However, the argument does show there are more potential reasons to create a sovereign wealth fund than critics, including me, have always thought. There are lots of non-oil producing countries that now have big funds, most notable Temasek of Singapore. Rwanda has one, Turkey has a big one, and some states, including Western Australia, and a whole bunch of US states have started funds over the past few years. The list is growing fast — countries are catching on.

These funds are nothing like the huge old state funds as in Norway, which has $1-trillion under management, or UAE’s Investment Authority with its $900-billion.

But Patel is right about one thing; you have to start somewhere. BM