ISS Today

Is mob violence out of control in South Africa?

Vigilantism is both a symptom and cause of a society where violence has become normalised. By Lizette Lancaster for ISS TODAY.

First published by ISS Today

At least two people a day die as a result of vigilante or group attacks in South Africa. One such incident recently went viral on social media. In the disturbing video, 28-year-old Thoriso Themane is dragged, assaulted and stoned by a mob that allegedly includes pupils from Capricorn High School in Limpopo. By 1 March, nine people had been arrested for the murder. Themane’s death traumatised family and friends, and those who witnessed his brutal attack.

National Police Commissioner General Khehla Sitole condemned the incident, saying “any act of vigilantism is as much criminal as the action of the person accused of committing a crime”.

Violence is so normalised in society that “ordinary” people commit horrific acts, at times in response to high levels of crime and perceptions that police and government crime-reduction strategies are ineffective.

In their analysis of the 2017/18 crime statistics, the South African Police Service (SAPS) associated at least 846 of the 20 336 murders with mob justice. The true figure is probably far higher because motives cannot be established in all murder cases, and the SAPS doesn’t formally quantify vigilante violence.

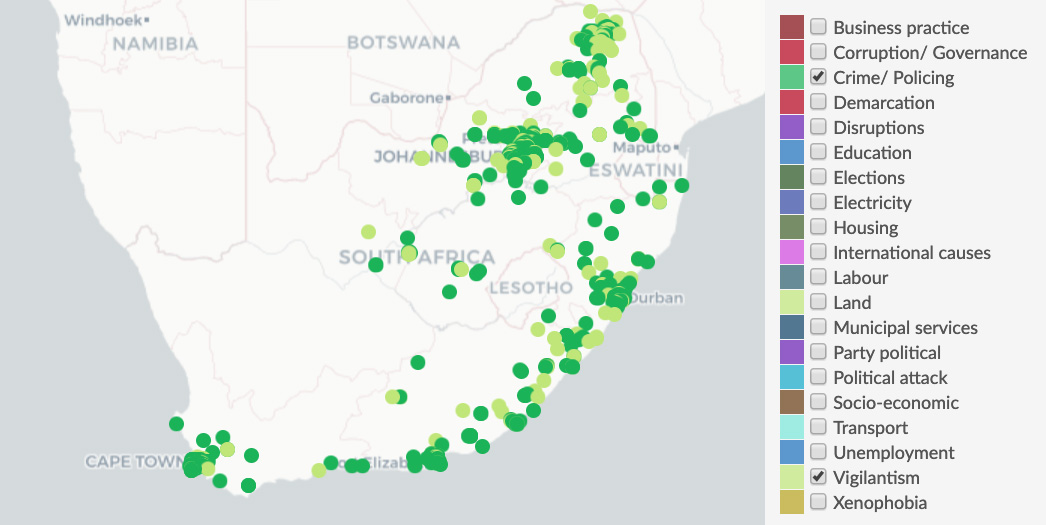

Protest research by the Institute for Security Studies (ISS) shows that many largely peaceful crime-related protests as well as vigilante attacks take place in South Africa every year (see map). Incidents mapped as part of the ISS’ public violence monitor are by no means exhaustive as the mainstream media tend to report only the most serious cases.

Source: CrimeHub

It is difficult to determine whether vigilantism and mob attacks are increasing because comprehensive statistics are not readily available. But vigilantism and group violence has occurred in South Africa for centuries in the absence of just and equitable law enforcement under colonial and apartheid governments.

Crime statistics suggest that many communities experience high levels of violence and crime. Public confidence in the criminal justice system is often low and people don’t trust the police to protect them. In fact, the latest Afrobarometer Survey for 2018 reveals that 66% of people mostly don’t trust the police and 46% don’t trust the courts.

Those who can, invest in private security and measures such as burglar bars, alarms, dogs and firearms for protection. The 2018 National Victims of Crime Survey by Statistics SA shows that 52% of households nationally use such measures to protect their homes. Eleven percent of households employ private security services, with Gauteng and the Western Cape usage being the highest at roughly 18%. Even with these measures, many still feel vulnerable.

Those who can’t afford security measures often feel neglected by the police and alone in protecting their families and homes. The crime survey also shows that 3.5% of households belong to self-help groups. These include self-defence classes or organised or semi-organised local groups.

Research shows that young men are most at risk of becoming both the victims and perpetrators of crime. It is therefore likely that they are also most at risk of becoming victims and perpetrators of “mob justice”.

In most instances when people intervene to stop crimes in progress, suspected offenders are caught and handed over to the police or traditional authorities. The problem comes when suspects are not only caught but also “punished”.

The cases that usually make it into the media are those in which suspects are killed. Death normally happens through beatings or stoning, but the most notorious method is apartheid-style “necklacing”, where a car tyre is placed around the suspect and set alight.

All types of mob or vigilante action run the risk of targeting innocent people who are in the wrong place at the wrong time. Despite their well-documented shortcomings, criminal justice systems in democracies are designed to be fair, with separate law enforcement and prosecutorial functions.

Importantly, the accused is allowed the opportunity to respond to the allegations and face the accusers in a safe environment. Most, if not all, of these principles fall away when an emotional crowd takes the law into their own hands.

The inevitable consequence of vigilantism is that sections of the community transition from largely law-abiding people into criminals. Once on this path, the state becomes secondary and private groups – be they gangs, militia or local businesses – become the alternative to government. They rule localities through the often arbitrary use of violence and fear.

People in these situations, particularly children exposed to violence often meted out on the whim of local warlords, experience severe insecurity and trauma.

The normalisation of violence that results increases the likelihood that violence is used to deal with stress and conflict in personal relationships and elsewhere in their lives. Violence then becomes a regular part of daily life, with few boundaries.

South Africa desperately needs effective, professional and responsive policing in high-violence communities. When there are clear violations of the law, the state must be seen to respond swiftly and fairly.

The country needs strong community leaders to condemn violence and take concerns of community members seriously. Children must be raised in supportive environments by parents who demonstrate other ways to resolve conflict besides violence. Social cohesion and tolerance of all people irrespective of nationality, sexual orientation and other qualities is needed.

But as long as South Africans feel the state cannot keep them safe, they are likely to seek their own justice, often with horrific repercussions. DM

Lizette Lancaster is manager of the Crime Hub, ISS Pretoria

Become an Insider

Become an Insider