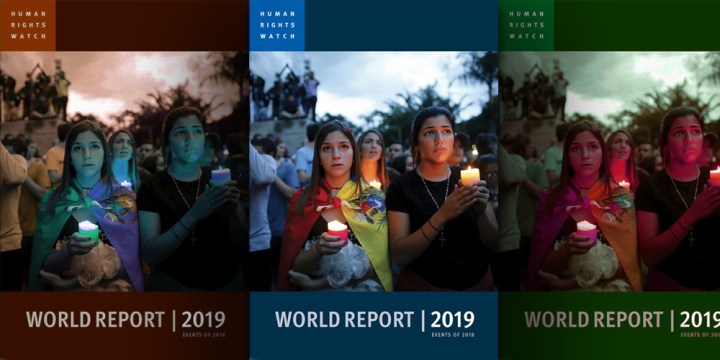

Human Rights Watch report

New crop of African leaders, same old repression and suffering

As fresh leaders rise to power resulting from civic movements’ demand for change, it seems that the new lot pays only lip-service to better governance. According to a Human Rights Watch report, human rights abuses continue even after electing new public officials.

When Dewa Mavhinga, director of Human Rights Watch in Southern Africa, arrived back home in Zimbabwe on 4 December for the holidays with his family, he could not believe the prices of goods on the shelf. He had just left South Africa — to where he emigrated and now stays permanently, and forgot to buy some Macadamia nuts he promised a friend who now lives in Tanzania. So when in Zimbabwe, he went into a mall, picked up a small 1kg bag of nuts and was shocked when the teller said they would cost him $146.

“It took me about two weeks for the shock to wear off,” said Mavhinga.

Mavhinga spent six weeks in Zimbabwe visiting family and his childhood village. Fortunately, he left just before the violence broke out over the rise in fuel prices.

“It is hard to find petrol in Zimbabwe. I had to call friends to ask them where to get fuel,” said Mavhinga.

For most people with cars, it became the norm to spend six or seven hours in a queue for fuel. One day, Mavhinga spent eight hours queueing. When he finally arrived at the pump his car had run out of fuel and there wasn’t any more petrol.

Many people had to leave their cars at the garage, as had become the norm, and walk a long way to buy petrol on the black market where five litres cost $35. He had to spend $70 for 10l. And it became worse as time went on, right through Christmas. People would spend all night waiting in long, winding queues to buy petrol.

The frustration came to a head in January when President Emmerson Mnangagwa announced a further fuel price increase.

And that is when the violence broke out. People took to the streets in Bulawayo and Harare to protest against the fuel hike and were met with heavily armed soldiers, reminiscent of the unrest that followed days after the 2018 elections. Reports came out of an internet shutdown, evoking recent memories of the former regime, ousted by the coup that was not a coup.

“What people don’t understand is how brutal the regime in Zimbabwe is and the level of brutality it is capable of. They don’t understand why people decide to leave and not fight back, as they suggest,” said Mavhinga.

‘It is not a regime that respects human rights’

A newly published report by Human Rights Watch finds that as new leaders emerge across Africa with renewed hope for greater respect for human rights, evidence on the ground suggests they pay lip-service to change but fail to live up to expectations.

The report documents events in 2018 in more than 100 countries globally with a specific focus on the rise of populists leaders who threaten human rights — and the civic movements that have arisen in resistance.

On Thursday 17 January in Rosebank, Johannesburg, Human Rights Watch launched the Southern Africa Report, coordinating it with similar launches in Berlin, London and Sao Paulo. A launch in Nairobi was cancelled because of the terror attack there this week.

The 2018 post-election violence and military crackdown in Zimbabwe is one instance of human rights abuses on the continent. The “extrajudicial killings of criminal suspects” and members of the LGBTQ community in Angola by President João Lourenco, displacement of thousands of people in Mozambique in the fight against Islamist armed groups and election violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo are all a cause for concern about continued disregard for human rights.

In South Africa, the report also noted the lack of accountability in xenophobic attacks and a lack of a comprehensive strategy to tackle gender-based violence.

South Africa’s poor human rights record remained unchanged after President Cyril Ramaphosa took office in February after Jacob Zuma’s resignation.

“Corruption, poverty, high unemployment, and violent crime significantly restricted South African’s enjoyment of their rights,” said the report.

Babatunde Olugboji, deputy programme director at Human Rights Watch, said at the launch of the report that traditional dictators, similarly to the present rise of new leaders, use a two-step strategy of scapegoating minorities and weakening checks and balances of power to secure their power.

Carine Nantulya, director of African Advocacy and a panellist at the launch, said the report showed three broad trends:

-

Elections as triggers of mass atrocities, while at the same time being a strong indicator of democratic transfer of power;

-

The need for justice after abuses have been made; and

-

The need for security against threats.

Now the “charade that under Mnangagwa, things would be different” is over, Zimbabwe has moved in a different direction and unfortunately, “its neighbours, including South Africa, have been silent”, said Nantulya.

“There seems to be no sense of urgency about the serious human rights abuses in Zimbabwe,” she said.

For Mavhinga, who was part of the panel, his home town Busiriro and childhood village Chivhu are almost unrecognisable after years of continued repression in Zimbabwe.

The high-density suburb of Budiriro, west of Harare, has become rural over the years, as more and more people now rely on rural activities to survive, such as collecting wood to make fires and digging wells for water, because the taps are dry.

And when he went to the rural farming village of Chivhu to visit his mother, he was surprised to see there are no young people there any more, but only widows and the elderly.

“The new crop of leaders across southern Africa should recognise that their citizens are expecting genuine improvement in human rights,” said Mavhinga.

The report also noted a rise in civic movements demanding change and holding public officials accountable.

For Nantulya, the hugely influential Catholic Church in the DRC has played a significant role in appointing election agents to monitor the electoral process. DM