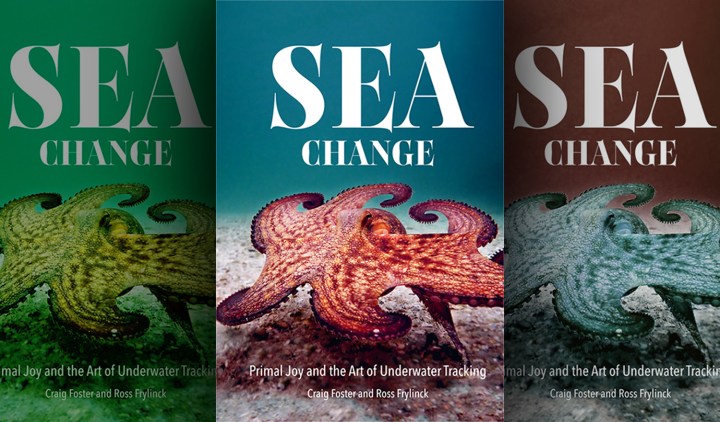

Book Extract

Sea Change: Primal Joy and the Art of Underwater Tracking

The authors spent eight years exploring the kelp forest of southern Africa, diving almost every day. Sea Change is the story of what they found in the wild, and how it has transformed their lives. Here follows a chapter, Cold and Scared, by Ross Frylinck, describing his therapeutic journey into a frigid underwater forest in winter to look for sharks.

See a video clip of Craig Foster’s underwater adventures above

A freezing wind swept across the Indian Ocean at the Cape of Storms in South Africa, blowing seagulls off their rocky perches. I stood at the water’s edge in a pair of board shorts and watched the birds as they spread their delicate grey wings to ride the current of air and then effortlessly settled down again and tucked in their heads.

Craig Foster stood a metre or so in front of me, knee-deep in the swirling ocean, squinting as he spat into his mask and rinsed it in the shallow sea water. He mentioned that he had a prescription lens in his mask and could hardly see without it. His imposing 1.9m body was marked by a long surgery scar on the left shoulder that accentuated this vulnerability. I guessed the scar was from a rugby injury and that he was in his mid-40s.

Out to sea, an ominous bank of storm clouds was building on the horizon. I felt the first raindrops sting my skin and noticed that all the fine hairs on my forearms were standing upright. My feet were aching and I realised with a pang of guilt that I was standing on a bed of sharp little mussel shells. I shifted my weight and hoped that I wasn’t crushing them.

Why was I even here, I wondered? I hardly knew this guy and yet I was about to follow him into a frigid underwater forest in winter to look for sharks. Worst of all, he had insisted that we dive without wet suits. Already I was cold and I hadn’t even entered the water yet. I had been swimming, surfing and diving in the icy seas around Cape Town for most of my life so I was no stranger to cold, but I always wore thick gloves, a hoodie and booties, leaving only my eyes and nose exposed. I truly hated the cold – and I wasn’t that mad about sharks either. As a surfer, I knew that sharks were always a threat; almost every year there was an attack in these waters.

I had crossed paths with Craig a few times over the years and followed his work as a natural history film maker. Then I bumped into him at a film festival and during our small talk in a crowded cinema aisle he mentioned that he was swimming alone in a kelp forest in False Bay every day. I wondered why anyone would swim through freezing underwater forests all on their own, every single day. There seemed to be no point to it, but for this very reason I was intrigued. When I asked him why, he paused, gave me an odd, piercing look and said he believed that the “sea forest was calling to me”. The crowd melted away and in the silence that followed I could think of nothing appropriate to say. I stood there feeling awkward as I stared into his blue eyes and was relieved when he finally broke the tension with an invitation to go swimming. Because I had nothing better to say, I agreed and we made a date.

Craig Foster in the frigid water. “When Ross joined me on that first dive, I had already been swimming in the kelp forest for three years. For the first year, swimming in the cold water was invigorating but difficult, and every dive ended in uncontrollable shivering. Crystal-clear waters rising from the Atlantic Ocean are usually cold, sometimes 9°C. Initially it was very difficult to convince myself to relax without a wetsuit. First the cold burns the skin and then the hands and feet go numb. The cold becomes a steel wall.” Photo: Ross Frylinck

Now, standing here on the rocks, I was regretting my decision, but it was too late to back out. I tightened my resolve and winced as I waded into the sea to join Craig, who was fiddling with his diving watch. I asked him what he was doing and he replied that he kept records of every dive: depth, temperature and duration. He casually mentioned that the temperature was 13°C, but because he didn’t seem concerned by this nasty fact I kept my dark thoughts to myself.

Just as we were about to submerge, we noticed a flash of movement in the clear water at our feet. Craig bent down and plucked a small fish out of the sea. He looked puzzled as he studied it, as if he was also surprised by what he had just done. He showed the shiny little pug of a fish to me, mentioned that it was a rocksucker and then let it go. I was amazed. Did that just happen? Did I see someone grab a fish out of the water? I had no time to process this any further because Craig sank into the sea and was gone. I didn’t want to be left behind so I rushed in after him.

As I dropped beneath the surface the cold crushed me and for the first few minutes I found myself in a brutal civil war. I had a manic urge to swim back to land, but pride held me back and so I followed Craig deeper into the kelp forest. An ice-cream headache pounded in my temples and I chewed on my rubbery snorkel until I cut my gums. Swimming directly behind Craig, I focused on the bubbles streaming off the soles of his kicking feet. My world was reduced to just four stark elements: cold, bubbles, the white soles of Craig’s feet and the amplified sound of my breathing.

Craig had been following a school of spotted gully sharks for a few weeks and he was excited to show them to me. He thought we would find them at the edge of the forest and so we swam about 300m out to sea, where the kelp was sparse and the water deep and dark. Resting for a moment in a clearing, I realised to my great surprise that I had warmed up a bit. I listened to the clicking sounds of the cracker shrimps and watched a large red roman swimming a few metres away. We eyed each other until it gave me a disdainful look and then vanished into the gloom.

As a teenager I had dived in these waters to hunt crayfish with my friends. I was comfortable inside the thick kelp forest and still had a surprisingly good breath-hold. It was easy enough to swim down to 10m with Craig, equalise my ears and hold onto the long kelp stipes while we looked for the sharks. Soon enough we noticed shadows gliding through the swaying forest and we knew that we had found what we were looking for.

I was mesmerised by their wild grace. They hardly paid us any attention, but I knew they were acutely aware of our presence. As I enjoyed watching them move so freely through the water, my normally crowded head seemed empty. I paused to look up at a shark gliding above me through the “trees”. Far above it, raindrops pitted the surface and storm clouds passed by. It was both surreal and beautiful, and I felt a wave of euphoria ripple through my body. I also noticed that the Red Roman had returned, along with a large school of Hottentot fish, and they were all looking at me. I returned the stare, feeling the enormity of the gulf between our species.

The spell was broken when I realised how cold I was. My fingers had curled into misshapen claws and were almost translucent with lack of blood. I tried to straighten them out so that I could swim, but the message didn’t get through and they stayed stubbornly crooked. I stared at them in mild horror and also realised that my jaw was shaking. Suddenly it was as if a steel gate had slammed shut on me and all the magic just vaporised. I was cold and scared and knew that I had to get out immediately.

I motioned to Craig that I was heading back and swam hard to shore. No longer able to feel my arms, I watched them dip in and out of the water in front of me as if I were seeing them in a film. Climbing onto the rocks was difficult. I felt drunk with the cold and the wind chill was pushing me over the edge. As I stumbled to my feet, it took all my strength to harness my fading will and pull on my down jacket. My numb, salty arms got stuck in the synthetic material and by the time I got it on I was exhausted. I tried to do up the zip, but my fingers were shaking so much that I had to give up. Craig came over and did it for me. I was amazed that his hands were calm.

He began to chuckle to himself and tried to hide this from me. When I questioned him, he pointed to my groin; I had wet my pants. A flash of embarrassment and then anger passed through me, but Craig’s chuckle had erupted into an innocent laugh and so, despite myself, I also burst out laughing. When this passed, I felt like I had been shot and collapsed into a nearby bush. I lay there for a while, allowing the shaking to continue. An elderly couple and their geriatric terrier came past and did a magnificent job of ignoring us. When I eventually managed to compose myself, Craig and I walked back up to his house on the mountain while the rain continued to fall.

Craig and his wife Swati Thiyagarajan, a well-known wildlife presenter in Asia, live in a wood-and-stone house that teeters on the steep mountainside above False Bay. Approaching their house, we arrived at a high rock-and-wattle wall – the kind you would expect to find protecting a cattle kraal in the veld. It’s an unusual façade in that suburban setting, especially next to the neighbours’ face-brick wall. There’s a large num-num bush by the front gate and we ate a few of the tart red berries before entering.

Walking down the tree-lined pathway to his house, I noticed a row of large, spherical stones and admired the fascinating engravings on some of them. They reminded me of crop-circle patterns, and when I asked Craig about them he said that he had spent a year carving into the stones with a dental drill. I found this an odd way to spend a year, but decided not to question him about it. When we reached his front door, I saw a rack of weathered diving odds and ends hanging on hooks and beneath them the rotting head of a giant tuna, its milky eyes staring blankly into the sky.

The blue dragon or sea swallow lives by floating on the open ocean, eating bluebottles and storing their stinging cells in its own body to repel predators. The literature says that these nudibranchs are dangerous to humans, but, says Craig Foster, they have touched his bare skin a few times and he’s experienced no adverse effects. Photo: Craig Foster

I was startled by the interior of his house, which was crammed with thousands of bones, shells, skins and indigenous artefacts. A weird skull drew me closer; it could have been a deer, but had a pair of the meanest fangs that gave it the look of a mythical beast. I wanted to explore some more, but I was soaked and shivering, so we took off our clothes and climbed into a small sauna perched against the side of the house. It was getting dark as we watched the storm pass over the sea far below. Craig poured some water and a few drops of peppermint oil onto the heated stones and as we warmed up we began to talk.

I told Craig that I had grown up on the Cape Peninsula, just a few kilometres away in Fish Hoek. This conservative, wind-blown valley town of ugly apartheid architecture was unremarkable to me, save for the mountains and lovely sheltered beach. Here I had fallen in love with the Peninsula and the kelp forests that fringe the coastline.

Craig told me that he was also immersed in these waters as a child. When he was three days old his parents brought him back to their small wooden bungalow that lay 30m from the ocean. For his baptism, his father took him down to the kelp forest and gently dipped him in the freezing water. He described waking up in the middle of the night to the sound of freak waves bashing down his door and flooding his bedroom. Like me, Craig started diving when he was very young and spent the early years of his childhood combing the rocky shore looking for washed-up artefacts and catching klipvis (rockfish) and crabs.

We both knew how lucky we were to have found the ocean wilderness so early and could track our careers back to these formative experiences. I had been working in ocean conservation for years, while Craig had developed a lifelong interest in wilderness survival and what he called “original design”. It was this interest that had brought him back to the Peninsula and the ocean after an emotional crash.

Craig spoke openly of his divorce and how the grief and guilt of leaving his wife and baby son had smashed him into pieces. He told me that he had spent two years travelling the world, diving with sharks and filming a way to hypnotise them through gentle touch. He rode on the backs of giant tiger sharks in the open ocean and swam freely among a shiver of five great white sharks, learning how to interact with the world’s largest predators. His next film took him into the ‘dragon’s lair’, where he pioneered the world’s first film on diving with Nile crocodiles in the Okavango Delta.

Craig told me stories about making this film that made me cringe in disbelief. Swimming through a long, narrow, murky underwater tunnel under the reeds, he came at last into the lair of a giant Nile crocodile. The 5m golden dragon stared at him unblinking from the back of its cave and it took his mind a good few seconds to register this epic scene. He later realised that he had been one of the first humans to enter the dragon’s den and live to tell the story. Although his team escaped harm, the next crew of divers was not so lucky. Hearing about Craig’s expedition, an adventure sports company arranged a tourist trip to dive with crocodiles in the swamps. On their first expedition a huge crocodile attacked one of the divers, ripping his arm off at the shoulder.

While Craig’s Okavango film was a great success, he realised he had taken risks that no one should take and he paid the price for putting himself under such intense stress for so many years. These experiences left him physically and emotionally exhausted. Overweight, sick and unhappy, Craig knew he needed healing that no doctor or therapist could offer. He moved to the Cape Peninsula and spent months just walking along the coastline at the nearby Cape Point Nature Reserve on his own. Walking turned to swimming and he soon found that he was feeling better. I remembered Craig as an emotionally distant person, but now I found him in great physical shape, warm and quick to laugh.

“Fear is often associated with not knowing animal behaviour. This compass jellyfish, with its bright colours, is pretending to be harmful, but it is harmless to humans, only able to sting small prey,’ say the authors. Photo: Craig Foster

I was going through my own slow-motion life crash. I had recently returned from central Java, where a surf trip had gone horribly wrong: my nine-month-old son Joseph contracted dengue fever – the leading cause of infant deaths in Asia. We spent an anxious week in a jungle far away from medical care; I knew that if things got really bad his cells would haemorrhage and he would bleed to death internally. Images of his small burning body covered in a rash still haunted me. I spent sleepless nights in the jungle compulsively composing a speech for his funeral, wrestling with the awful guilt I was feeling for taking him into such a remote place, especially since he was already weak from a premature birth.

Joseph had been born three months early, weighing only 900g. I told Craig how I had put my wedding ring on his leg and felt overwhelmed with fear when it slid all the way to the top of his thigh. My wife Justine and I spent two months in the neonatal ICU ward and for 15 hours a day we took shifts holding Joseph to our chests, obsessively watching the monitors that displayed his vital signs. Babies I would never know struggled for their lives in little glass cases and I couldn’t believe the operations that were being performed on such tiny, fragile beings. The horror of that time was scorched into my memory; it felt like my mind had become dislocated. Eighteen months later the shadow still fell over me.

We finished our sauna and Craig offered me a snack of buffalo milk and raw wildebeest, which we ate with miso paste. It was delicious. By now I was exhausted and beyond being surprised by this strange giant. On the long drive back home to the centre of Cape Town, I felt somehow cleaner, as if I had been washed on the inside. My senses were also far sharper and it seemed as if I had a new, more expensive stereo system in my car – the audio sounded that much better. I was happy for the first time in months as I drove along the dark, empty coastal road, singing to myself while the rain fell. DM

Sea Change is published by Quivertree Publications. In 2012, Craig Foster and Ross Frylinck founded the Sea-Change Trust, which is a community of scientists, storytellers, journalists and filmmakers who are dedicated to exploring and conserving the ocean.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider