Maverick Life, South Africa

Book Extract: The Presidency and the Constitution, from Mandla Langa’s Dare Not Linger

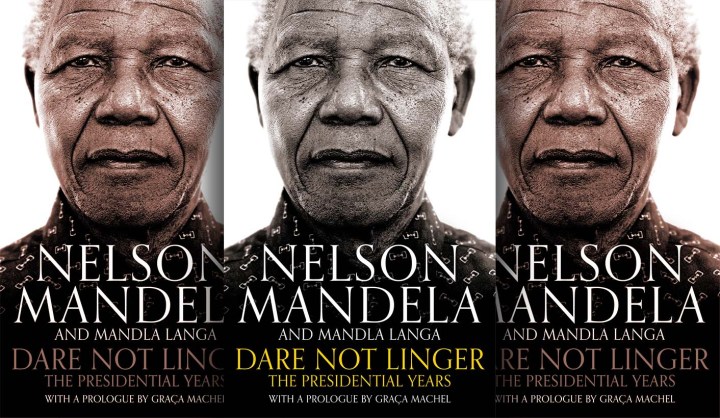

Dare Not Linger is the story of Nelson Mandela’s presidential years, drawing heavily on the memoir he began to write as he prepared to conclude his term of office, but was unable to finish. MANDLA LANGA has completed the task, using Mandela’s unfinished draft, detailed notes Mandela made as events were unfolding, and a wealth of unseen archive material. In this extract, from the chapter, The Presidency and the Constitution, Langa reveals a president willing to subject himself to the rule of law to show his commitment to ‘abide by the decisions of our courts’ and that ‘all South Africans should likewise accept their rulings. The independence of the judiciary is one important pillar of our democracy.’

As president, Nelson Mandela’s relationship with the judiciary would be severely tested. And for someone who ended up presiding over the creation of one of the world’s most admired constitutions, Mandela’s relationship with South Africa’s courts had not always been favourable. As a young lawyer he’d had constant skirmishes with magistrates who objected to his seemingly “uppity” attitude. It didn’t help that he was six foot two inches and always immaculately dressed during court appearances, projecting an image that was inimical to the old-school image of an African. He also had a disconcerting knack of ensuring that, whatever the subject of proceedings, he found his way back to what he really wanted to talk about.

The speech he made from the dock on 20 April 1964, during the last months of the Rivonia Trial, is a case in point. Facing a probable death sentence, Mandela told the court – and the world – that he had “cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

It was only in prison that Mandela completed part-time the law degree he had started in 1949. Through years of study he had been unable to complete the degree at the University of the Witwatersrand. But, incarcerated on Robben Island, he studied for his LLB from the University of South Africa (Unisa) by correspondence, finally graduating in absentia in 1989.

After his release, his first encounter with the justice system was an affront to his dignity when he sat – a lonely, if stoical, figure – in the public gallery of the Rand Supreme Court in May 1991, witnessing the mortification of his then wife, Winnie, on trial for assault and kidnapping.

Subsequently, in matters that affected him as president, Mandela’s relationship with the judiciary was tested in two instances. Would he, when it came to matters that affected him personally, remember his oath of office and heed the ponderous words that defined his role as president, head of state and head of the national executive? Had he internalised the fact that to hold the highest office in the land made him, as first citizen of his country, indispensable to the effective governance of democratic South Africa? Would he uphold‚ defend and respect the Constitution as the supreme law of the Republic? Would he affirm that “in the new South Africa there is nobody, not even the President, who is above the law, that the rule of law generally and, in particular, the independence of the judiciary should be respected”?

The first test came even before the new constitution had been drafted. Running into deadlines for preparations for local government elections, Parliament adopted the Local Government Transition Act before its terms had been completely finalised. To compensate for this, a clause was included giving the president power to amend the Act. Armed with that provision, Mandela transferred control over the membership of local government demarcation committees from provincial to national government. However, that invalidated decisions made by the premier of the Western Cape, Hernus Kriel, who took the matter to the Constitutional Court. The court found for the Western Cape provincial government and gave Parliament a month to rectify the Act.

Within an hour of the court delivering its adverse judgment, Mandela publicly accepted the ruling and welcomed the fact that it showed that everyone was equal before the law. Later, he wrote:

“During my presidency, Parliament authorised me to issue two proclamations dealing with the elections in the Western Cape province. That provincial government took me to the Constitutional Court, which overruled me in a unanimous judgment. As soon as I was informed of the judgment, I called a press conference and appealed to the general public to respect the decision of the highest court in the land on constitutional matters.”

Mandela discussed the court judgment with his advisers and the Speaker of Parliament, Frene Ginwala. She remembers the day:

“He called us to a meeting at his house and told us that he had been informed that it had gone against the government. He said, ‘How long will it take to change?’ I said, ‘We could reconvene Parliament if necessary …’ but even before I could finish, he said, ‘But the one thing is this: we must respect the decision of the Constitutional Court. There can be no question of denying or in any way rejecting that.’”

In a public statement, he went further, announcing that Parliament would be reconvened to deal with the matter and stressing that, apart from Cape Town, things were on track for the elections:

“Preparations for local government elections must continue so that these elections take place as planned. The Court’s judgment does not create any crisis whatsoever. I should emphasise that the judgment of the Constitutional Court confirms that our new democracy is taking firm root and that nobody is above the law.”

Mandela was somewhat less sanguine when it came to the other case that had him personally appearing in court. He had worked hard, using the iconic victory in the 1995 Rugby World Cup, to entrench the spirit of nation building and reconciliation among South Africans. But the euphoric surge of unity and embrace of the future had remained within the perimeter of the Ellis Park Stadium, amid the debris of trash and match memorabilia. For some of the spectators, players and rugby administrators, everything was as it had been before the match. Two years on, prompted by reports of maladministration, resistance to change and racism in the sport’s governing body, after consultation with Minister of Sport and Recreation Steve Tshwete, Mandela appointed a commission of inquiry, led by Justice Jules Browde, to look into the affairs of the South African Rugby Football Union (SARFU).

The president of SARFU, Louis Luyt, best described as a carpetbagger, had in 1976 founded an English-language newspaper, The Citizen, using slush funds from the Department of Information, in what was known as the “Infogate Scandal”, which purveyed propaganda aimed at polishing the apartheid government’s image overseas. Singularly unlikeable, Luyt had precipitated a walkout by the New Zealand All Blacks rugby team when, instead of being magnanimous in victory, he made inappropriate remarks at the after-match dinner.

The President’s office issued a statement, saying that “the cloud hanging over South African Rugby needs to be lifted and the President is confident that the inquiry presents an opportunity to do so, and to dispel any impression that … it is retreating into a laager of racial chauvinism. The President believes that rugby will meet the challenge of being one of our most celebrated sports, a sport played and supported by South Africans throughout the country.”

Mandela’s intention was to help pull SARFU out of its “laager of racial chauvinism” but it simply prompted its president, Louis Luyt, to apply to the Pretoria High Court to quash the appointment of a commission of inquiry into the administration of rugby. Judge William de Villiers summoned Mandela to appear before the court as a witness. Not only setting aside legal advice, but also controlling his own feelings – having to testify in court “made his blood boil”, he told journalists – Mandela complied, in the interests of justice. He writes about the episode:

“Judge William de Villiers of the Gauteng High Court subpoenaed me to appear before him to justify my decision to appoint a commission of enquiry into the affairs of the South African Rugby Football Union. Some of my Cabinet colleagues advised me to challenge the subpoena, pointing out that the judge in question was, to say the least, extremely conservative, and that his real aim was to humiliate a black president.

“My legal adviser as well, Professor Fink Haysom, was equally opposed to my appearance in court. He argued with skill and persuasion that we had sound legal grounds to challenge the subpoena.

“While I did not necessarily challenge any of these views, I felt that at that stage in the transformation of our country, the President had certain obligations to fulfil. I argued that the trial judge was not a final Court of Appeal, and that his decision could be challenged in the Constitutional Court. In a nutshell, I wanted the whole dispute to be resolved solely by the judiciary. This, in my opinion, was another way of promoting respect for law and order and, once again, of the courts of the country.

“As we expected, the judge had serious reservations about my evidence, and gave judgment for Louis Luyt, the petitioner. But the Constitutional Court set aside the decision of the lower court despite the fact that they maintained that my attitude in testifying was imperious. The Constitutional Court was not wrong. In that situation I have to be bossy and establish that I obeyed the subpoena out of strength and not weakness.”

Mandela’s reaction to the ruling in SARFU’s favour was his commitment to “abide by the decisions of our courts”. He said that “all South Africans should likewise accept their rulings. The independence of the judiciary is one important pillar of our democracy.”

Addressing Parliament later in April, Mandela told the assembled members that they would have to ask themselves “some very basic questions”, as it was “only too easy to stir up the baser feelings that exist in any society that are enhanced in a society with a history such as ours. Worse still, it is only too easy to do this in a way that undermines our achievements in building national unity and enhancing the legitimacy of our democratic institutions. We need to ask such questions because it is much easier to destroy than to build.”

He enjoined the Members of Parliament to grapple with constitutional questions, such as the implications of hauling a sitting president to court to “defend executive decisions”, going straight to the principle of the separation of powers and its application in an emergent democracy. He hoped that “our best legal brains, both in the courts and in the profession” would apply their minds to the question.

As a trained lawyer, Mandela probably knew the answers to the questions he was posing, but he was dealing with the Constitution, which he saw as a foundation for the building of democracy – a democracy whose central plank was national unity and reconciliation. He wanted everyone’s buy-in, no matter that his own interpretations might have been both correct and justifiable. His appeal to the parliamentarians, then, was for them, in their disparate parties, to help build rather than destroy.

By the time the Constitutional Court set aside the Pretoria High Court ruling that the president had acted unconstitutionally, reaction to Louis Luyt’s behaviour – among the public and within rugby – had forced his resignation and led to a decision by the SARFU executive to send a delegation to apologise to Mandela.

Although not codified until the negotiations of the 1990s, the principles of constitutionalism and rule of law had been embedded in the vision of the future shared by Mandela and the ANC at large. The seeds of an empowering constitution can be found in the Freedom Charter, adopted by the Congress of the People and the ANC respectively in 1955, which was drawn up on the basis of popular demands collected from communities across the length and breadth of the country.

Contrary to what happened in struggles for freedom in many other countries, the South African liberation movement made the law a terrain of struggle – defending leaders, members and activists in the courts – and in so doing, affirming the ideal of a just legal system. In 1995, in a lecture, Mandela spoke about using the law to turn tables on the state, as he and the other accused did in the Rivonia Trial:

“The prosecution expected us to try and avoid responsibility for our actions. However, we became the accusers, and, right at the start, when asked to plead, we said that it was the Government that was responsible for the state of affairs in the country and that it was the Government that should be in the dock. We maintained this position throughout the trial in our evidence and in the cross-examination of witnesses.” DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider